- Experts

- Election 2024

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedThis interactive examines how nationwide bans on menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars, as proposed by the Biden administration on April 28, 2022, could help shrink the racial gap on U.S. lung cancer death rates.

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

FeaturedThe rapidly changing landscape of foreign influence demands a new approach, argues Senior Fellow for Global Governance Miles Kahler. Countering malign influence from abroad will require a stronger democracy at home.

Council Special Report by Miles Kahler October 23, 2024 Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedThis symposium was created to address the broad spectrum of issues affecting Wall Street and international economics. It was established through the generous support of Council board member Stephen C. Freidheim and is copresented by the Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies and RealEcon: Reimagining American Economic Leadership.

Virtual Event with Emily J. Blanchard, Matthew P. Goodman, David R. Malpass, Elizabeth Rosenberg, Janet Yellen, Michael Froman and Rebecca Patterson October 17, 2024 Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies

- Related Sites

- More

Economics

Financial Markets

-

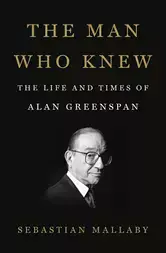

The Man Who Knew

![]() In this biography of Alan Greenspan, Sebastian Mallaby brilliantly explores Greenspan's life and legacy and tells the story of the making of modern finance.

In this biography of Alan Greenspan, Sebastian Mallaby brilliantly explores Greenspan's life and legacy and tells the story of the making of modern finance. -

Won Appreciates, South Korea IntervenesSouth Korea’s tendency to intervene to limit the won’s appreciation is well known. When the won appreciated toward 1100 (won to the dollar) last week, it wasn’t that hard to predict that reports of Korean intervention would soon follow. Last Thursday Reuters wrote: "The South Korean currency, emerging Asia’s best performer this year, pared some gains as foreign exchange authorities were suspected of intervening to stem further appreciation, traders said. The authorities were spotted around 1,101, they added. " The won did appreciate to 1095 or so Tuesday, when the Mexican peso rallied, and has subsequently hovered around that level. It is now firmly in the range that generated intervention in August. The South Koreans are the current masters of competitive non-appreciation. I suspect the credibility of Korea’s intervention threat helps limit the scale of their actual intervention. And with South Korea’s government pension fund now building up foreign assets at a rapid clip, the amount that the central bank needs to actually buy in the market has been structurally reduced. Especially if the National Pension Service plays with its foreign currency hedge ratio to help the Bank of Korea out a bit (See this Bloomberg article; a “lower hedge ratio will boost demand for the dollar in the spot market" per Jeon Seung Ji of Samsung Futures). Foreign exchange intervention to limit appreciation isn’t as prevalent it once was. More big central banks are selling than are buying. But it also hasn’t entirely gone away. Korea has plenty of fiscal space. It could move toward a better equilibrium, one with more internal demand, less intervention and less dependence on exports.

-

The Most Interesting FX Story in Asia is Now Korea, Not ChinaChina released its end-August reserves, and there isn’t all that much to see. Valuation changes from currency moves do not seem to have been a big factor in August, the headline fall of around $15 billion is a reasnable estimate of the real fall. The best intervention measures -- fx settlement, the PBOC balance sheet data -- aren’t out for August. Those indicators suggest modest sales in July, and the change in headline reserves points to similar sales in August. That should be expected. China’s currency depreciated a bit against the dollar late in August. In my view, the market for the renminbi is still fundamentally a bet on where China’s policy makers want the renminbi to go, so any depreciation (still) tends to generate outflows and the need to intervene to keep the pace of depreciation measured.* Foreign exchange sales are thus correlated with depreciation. But the scale of the reserve fall right now doesn’t suggest any pressure that China cannot manage. That is one reason why the market has remained calm. Indeed the picture in the rest of Asia could not be more different than last August, or in January. The won for example sold off last August and last January. More than (even) Korea wanted. During the periods of most intense stress on China, the Koreans sold reserves to keep the won from weakening further. Not this summer. The slow measured slide in China’s currency against its basket hasn’t translated into selling pressure elsewhere. And Korea is now quite clearly intervening to keep the won from strengthening. In July, the rise in headline reserves, the rise in the Bank of Korea’s forward book, and the balance of payments data all point to over $3 billion in purchases (the forward book, one of the best measures of what might be called Korea’s shadow reserves, matters; it rose by over a billion in July). There is only data for headline reserves for August at this stage, and this points to a further $4 billion in intervention. Scaled to Korea’s GDP, Korea bought about two times as much as China appears to have sold. And I would bet Korea’s forward book also increased, so the full count for August could be higher still. And with the won flirting with 1090, the level that triggered reports of heavy intervention in mid-August, the market quite reasonably is on intervention watch again. I am a long-standing fan of Reuters’ coverage of Asian fx markets. Reuters reported on Wednesday: "The won rose as much as 1.2 percent to 1,092.4 per dollar, compared with a near 15-month high of 1,091.8 hit on Aug 10 ... The South Korean currency pared some of its earlier gains as finance ministry officials said the authorities are ready to take action in case of excessive currency movements. The warning boosted caution over possible intervention to stem further strength ..." Taiwan’s rising reserves also clearly suggest that it too is buying foreign currency. All this is very different from periods of acute China stress. I should also note that with short-term external debt of around $100 billion and over $400 billion in reserves (counting its forward book) Korea is very well reserved by traditional metrics. It even has more than enough reserves on the IMF’s metric (p. 34 of the staff report), and the IMF’s new reserve metric tends to inflate Korea’s reserve need relative to traditional balance sheet measures: Korea has a high exports to GDP ratio and a relatively high M2 to GDP ratio. If you haven’t guessed, I am not a fan of the new reserve metric’s tendency to call on economies with large external surpluses to hold more reserves, relative to their economy, than their peers with external deficits. * China reportedly intervened a bit after the G-20 meeting for example, as some believe China will now resume a controlled depreciation.

-

The 2016 Yuan DepreciationThe Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) broad effective index is the gold standard for assessing exchange rates. And the BIS shows—building on a point that George Magnus has made—that China’s currency, measured against a basket of its trading partners, has depreciated significantly since last summer. And since the start of the year. On the BIS index, the yuan is now down around 7 percent YTD. Those who were convinced that the broad yuan was significantly overvalued last summer liked to note how much China’s currency had appreciated since 2005. But 2005 was the yuan’s long-term low. And the size of China’s current account surplus in 2006 and 2007 suggests that the yuan was significantly undervalued in 2005 (remember, currencies have an impact with a lag). I prefer to go back to around 2000. The yuan is now up about 20 percent since then (since the of end of 2001 or early 2002 to be more precise). And twenty percent over 15 years isn’t all that much, really. Remember that over this time period China has seen enormous increases in productivity (WTO accession and all). China exported just over $200 billion in manufactures in 2000. By 2015, that was over $2 trillion. Its manufacturing surplus has gone from around $50 billion to around $900 billion. China’s global trade footprint has changed dramatically since 2000, and a country should appreciate in real terms during its “catch-up” phase. In 2014 and early 2015, the broad yuan clearly appreciated at a much faster rate than had been typical after 2004. Out of curiosity, I drew a trend line from end 2004 to 2012. With the recent depreciation, the broad yuan is more or less now back on that trend line. You can argue that the pace of appreciation implied by the trend line (about 3.5 percent a year) is too fast now, as it reflects an initial appreciation from a structural undervaluation. But if you are thinking about the right fundamental level of yuan, not just the pace of appreciation, you would also need take into account the 2000-2004 depreciation. If you think the right average pace of appreciation over the last fifteen years—given China’s catch-up—is 1.5 percent a year, China would now be close to a trend line starting in 2000. And a few years back William Cline of the Peterson Institute estimated that China’s real exchange rate needed to appreciate by about 1.7 percent a year (call it 1.5 to 2 percent) to keep China’s current account surplus constant. It is a debate. For one, a linear pace of appreciation almost certainly isn’t right, as presumably productivity growth (and relative productivity growth) hasn’t been constant. No matter, one point is clear: the yuan isn’t as strong as it was a year ago. And that is starting to show in the trade data. Chinese goods export volumes were up 5 percent year-over-year in the last four months of data (q2 plus July). That is a much faster pace of increase than for say the United States (U.S. non-petrol goods export volumes were down well over 2 percent in q2). The following chart would not pass peer review muster. I had to convert nominal exports into real exports using a price index that is also derived from the reported percent changes (China really should produce better data here). But I think it captures something significant: In q2 2016 and July, it seems likely that China’s (goods) exports grew a bit faster than overall world trade. That doesn’t scream "over-valuation." And to my mind it makes the trade data for q3 all the more important.

-

Is The Dirty Little Secret of FX Intervention That It Works?Foreign exchange intervention has long been one of those things that works better in practice than in theory.* Emerging markets worried about currency appreciation certainly seem to believe it works, even if the IMF doesn’t.** Korea a few weeks back, for example. Korea reportedly intervened—in scale and fairly visibly—when the won reached 1090 against the dollar in mid-August: "Traders said South Korean foreign exchange authorities were spotted weakening the won "aggressively," causing them to rush to unwind bets on further appreciation. On Wednesday (August 10), according to the traders, authorities intervened and spent an estimated $2 billion when the won hit a near 15-month high of 1,091.8." And, guess what, the won subsequently has remained weaker than 1090, in part because of expectations that the government will intervene again. And of course the Fed. And that is how I suspect intervention can have an impact in practice. Intervention sets a cap on how much a currency is likely to appreciate. At certain levels, the government will resist appreciation, strongly—while happily staying out of the market if the currency depreciates. That changes the payoff in the market from bets on the currency. At the level of expected intervention; appreciation becomes less likely, and depreciation more likely.*** 1090 won-to-the-dollar incidentally is still a pretty weak level for the won, even if the Koreans do not think so. The won rose to around 900 before the crisis, and back in 2014, it got to 1050 and then 1000 before hitting a block in the market. In the first seven months of 2016, the won’s value, in real terms, against a broad basket of currencies was about 15 percent lower than it was on average from 2005 to 2007. My guess is that Korea’s practice of intervening to cap the won’s appreciation at certain levels—and systematically trying to keep the won weaker than it was from 2005 to 2008 is part of the reason why Korea runs such a large current account surplus. Just a hunch. Korea’s tight fiscal policy no doubt contributes to Korea’s large external surplus as well (Korea’s social security fund runs persistent surpluses, surpluses that generally have more than offset the government’s small headline deficit). Intervention and tight fiscal sort of work together. The general government surplus acts as a restraint on domestic demand. And intervention helps sustain a large export sector that offsets weakness in internal demand. [*] More specifically sterilized intervention (sterilized intervention means the government buys foreign currency, but offsets the domestic monetary impact of its foreign exchange purchases—whether by raising reserve requirements, issuing central bank paper, or by selling domestic assets). Unsterilized purchases of foreign exchange are a monetary expansion, and thus always should have an exchange rate impact. This San Francisco Fed note is a bit old, but it gives a clear summary of the standard argument while arguing that intervention can have an impact; this Cleveland Fed paper is typical of the view that sterilized intervention doesn’t have an impact. [**] The IMF formally believes—if belief is defined by what is in its workhorse current account model—that foreign exchange intervention only has an impact when a country’s financial account is largely closed. For example, even extremely large scale intervention by say Japan technically would have no impact on Japan’s current account, as Japan’s financial account is considered fully open, and intervention is interacted with the coefficient for openness. Korea’s capital account isn’t fully open, but it is pretty open—so 1 percent of GDP in intervention would, in the IMF’s model estimates, I think have a maximum impact of around 5 basis points (0.05 percent of GDP) on Korea’s current account (the 0.45 coefficient on reserve growth times the 0.13 coefficient on the capital account). However, intervention is only judged to be policy relevant by IMF if there is a gap between the country’s level of reserves and the optimal level of reserves, and if there is also a gap between the country’s controls and the optimal level of controls. As the IMF doesn’t think Korea should throw open its financial account just yet, Korea’s intervention is effectively zeroed out. Joe Gagnon, Taim Bayoumi and Christian Saborowski found a bigger impact from intervention in their 2014 paper: “each dollar of net official flows raises the current account 18 cents with high capital mobility and 66 cents with low capital mobility, for an average effect of 42 cents.” The impact of an incremental 1 percent of GDP in reserve purchases by Korea is thus about 20 basis points on the current account, plus an additional impact from the legacy of past intervention. A high stock of reserves has an impact in the Bayoumi, Gagnon and Sabrowski model on the current account balance of high capital mobility countries. Korea has well over $400 billion in reserves if you include its $44 billion forward book, or very roughly around 30 percent of GDP; with a stock coefficient of .03 that gives a stock impact of around 1 percent of GDP. Other Gagnon estimates point to a slightly bigger impact of intervention. My guess is that Korea’s long record of intervening to cap appreciation together with its less than complete financial openness combine so that Korea’s actions have a bigger impact than implied by the Gagnon, Bayoumi, and Sabrowski estimates, as past intervention makes Korea’s action in the market more credible (e.g. the market believes that if Korea really wants to stop the won from appreciating it will buy in scale, so it doesn’t test the authorities too much once they show their hand).

-

Home Truths About the Size of Nigeria’s EconomyIn 2014, following the first revision of Nigeria’s gross domestic product data in two decades, Abuja announced that its economy had overtaken South Africa’s as the largest in Africa. Using the rebased data, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that that Nigeria’s economy grew at 12.7 percent between 2012 and 2013. Thereafter, there was some triumphalist rhetoric about the size and strength of the economy from personalities in then-president Goodluck Jonathan’s administration in the run up to the 2015 elections and among those promoting foreign investment in Nigeria. However, in 2016, reflecting the dramatic fall in petroleum prices and the value of the national currency, the naira, the IMF concluded that Nigeria’s GDP had fallen behind that of South Africa. The Economist noted that foreign investors are likely to be discouraged by the latest figures. A clear-eyed August 22 editorial, Vanguard, an independent, national-circulating newspaper based in Lagos, argued that Nigeria’s economic was “never as strong as the 2014/15 rebasing of the GDP had portrayed.” Instead, Nigeria’s economy was “like a clay-footed elephant that could collapse under the slightest pressure. Thus, it took just a slide in oil revenue compounded by ineffective policy responses to it…to bring the elephant down.” Among the home truths cited by Vanguard: —Even when its GDP was higher, Nigerians were “almost four times poorer” than South Africans. —Nigeria has been unable to exploit its domestic market because of low production capacity. —Nigeria’s huge population is not sufficiently channeled into economic productive activity. —Vanguard concludes that Nigeria must diversify its economy and develop local industrial production if it is to thrive. Nigeria’s current population estimates are in the range of 187 million. A UN agency estimates that by 2050, the country’s population will be around 400 million, making it the largest country in the world. It is the current size of the Nigerian market, and its potential future size, that has fascinated investors. Yet, far from being a blessing, a huge population that is growing rapidly is a drag on national development when education, health, and other basic infrastructure is inadequate to engage it in productive activity.

-

The Absence of Foreign Demand for Treasuries in the TIC data Is a Bit MisleadingA common explanation for low Treasury yields is that low rates outside the United States have piled into the U.S. market, as investors in Europe, Japan and elsewhere look to the United States for a reasonable mix of safety and yield. That is part of what Gavyn Davies, in one of his typically thoughtful posts, argues that the Fed has learned over the past year. The United States is no longer a (monetary) island, the rest of the world matters. Of course, what Lael Brainard called the elevated sensitivity of exchange rate moves to monetary surprises is also a part of the global story. It isn’t just a flows story. An awful lot of the tightening in U.S. financial conditions that occurred in anticipation of the Fed raising rates came through dollar appreciation; too much in my view. The apparent problem with this the "foreign demand is holding down Treasury yields" thesis: Foreign investors pretty clearly have sold Treasuries over the past 12 months. And not just a few Treasuries. Net foreign sales of long-term Treasuries over the last 12 months of data are around $250 billion. So what is going on? It is actually pretty simple, in my view. Treasury sales in the Treasury International Capital (TIC) data (and also, I suspect, most of the sales of U.S. equities) are linked to the fall in global reserves. Over the last 12 months China has sold several hundred billion of reserves (though most of those sales were in the fall of 2015 and early 2016, recent sales are more modest), the Saudis have been selling and Japan—for reasons of its own—has been selling securities while increasing its deposits (Japan has reduced its long-term securities holdings by a bit over $100 billion over the last two years, while raising its short-term deposits by a similar amount, according to the SDDS data). A plot of estimated growth in global reserves (I sum the reserves of a broad set of countries, and assume the currency distribution of reserves maps to the IMF COFER data on reporting countries) against official bond sales in the TIC data suggest the official sales are in line with the fall in global reserves. So why hasn’t the fall in official demand for Treasuries had an impact on Treasury yields? Well, China’s reserve sales have come with a globally deflationary shock. The yuan has depreciated over the last year, and weakness in Chinese investment demand has pulled down commodity prices (the IMF estimated that between 20 and 50 percent of the fall in broad global commodity indices over the past few years is due to China; see paragraph 18). In that context, there is little reason to think China’s sales should be driving up U.S. yields. Particularly not when China’s current account surplus—and thus the net acquisition of foreign assets (or net reduction in foreign debt) by Chinese residents—is still around $250 billion (it was over $300 billion in 2015, but fell a bit in the first half of 2016). Official Chinese sales of Treasuries are offset by a buildup of private Chinese assets abroad (even if they are hard to track) and the repayment of debts Chinese residents owe to the world’s banks. Big repayments too. The banks then have to park the funds formerly lent to China somewhere. If you strip out official sales, foreign private demand for Treasuries looks solid. And more importantly, foreign private demand for U.S. bonds of all kinds, including close substitutes for Treasuries, is actually pretty strong. Right now, unlike in many past periods (2005 to 2007 for example, or 2010 and 2011) I suspect most of the "private" purchases of Treasuries and Agencies in the TIC data are actually private purchases, not official purchases in disguise. And then there is another, hidden source of inflows into the U.S. bond market. American investors, faced with low yields on their foreign bonds, have been selling off their foreign portfolio and bringing the proceeds home. To the tune of $270 billion over the last 12 months. Sum up American selling a portion of their existing holdings of foreign bonds and bringing the money home and around $400 billion in foreign private purchases, and there is an almost $700 billion net inflow from private fixed income investors in to the United States. One small subcomponent of all this: foreign investors have rediscovered their love for Agency bonds. You need to go back to the summer of 2007 to find as much foreign demand for long-term Agencies as was recorded in the TIC data this June. Throw in the fact that the Fed is clearly in the process of rethinking the path of U.S. policy rates (and Larry Summers is rethinking the Fed’s policy target) and current U.S. yields are easier to understand.

-

The Outsized Impact of the Fall in Commodity Prices on Global TradeGlobal trade has not grown since the start of 2015. Emerging market imports appear to be running somewhat below their 2014 levels. Creeping protectionism? Perhaps. But for now the underlying national data points to much more prosaic explanation. The "turning" point in trade came just after oil prices fell. And sharp falls in commodity prices in turn radically reduced the export revenues of many commodity-exporting emerging economies. For many, a fall in export revenue meant a fall in their ability to pay for imports (and fairly significant recessions). For the oil exporters obviously, but also for iron exporters like Brazil. Consider a plot of real imports of six major world economies: Brazil, China, India, Russia, the eurozone and the United States, indexed to 2012. The underlying data isn’t totally comparable. I used seasonally adjusted real goods and services imports from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) data for Brazil, India, Russia and the eurozone. For China I used an index of import volumes, and smoothed it by taking a four quarter average (necessary, alas as the seasonality overwhelms the trend, even though it doesn’t make the data for China fully comparable with the data for the others countries). And for the United States I wanted to take out oil imports, and the easiest way to do that is to look at real non-petrol goods imports. I see five things in this data: (1) The 20-30 percent fall in Brazilian and Russian imports from their 2012 levels, which rather obviously is mostly tied to changes in their terms of trade. Brazil and Russia are fairly large economies, and these are giant falls. (2) An adjustment in India that followed the now almost forgotten taper tantrum (I didn’t adjust for gold imports). (3) A slowdown in import growth in China that started in 2014 and was quite pronounced in 2015. And more generally, relatively slow growth in import volumes relative to China’s reported GDP growth. Pick your favorite explanation. The most obvious is that the most import-intensive parts of the Chinese economy have slowed the most. The imported content of domestic consumption is low. And China is producing more and more electronic components. Manufactured imports have been trending down relative to China’s GDP for some time. (4) Decent import volume growth, rather surprisingly, from the eurozone. Admittedly, this is a recovery from a really low base. But the slow recovery in the eurozone that took hold a few years ago has flowed through to demand for the goods of the rest of the world. (5) Decent import growth in the United States until 2015 if you remove the impact of the tight oil revolution. Rising U.S. oil production from 2012 to 2015 obviously led to a reduction in oil import volumes, which is natural if there a big increase in supply in one of the world’s largest importers. And over the last several quarters, U.S. import growth, rather mysteriously, has slowed. The best explanation I think is that weakness in investment feeds through more strongly into imports than ongoing growth in domestic consumption, but I concede the weakness in imports in the face of dollar strength is a bit of a mystery.

-

China’s Asymmetric Basket PegThe implications of Brexit understandably have dominated the global economic policy debate. But there are issues other than Brexit that could also have a large global impact: most obviously China and its currency. The yuan rather quietly hit multi-year lows against the dollar last week. And today the yuan-to-dollar exchange rate (as well as the offshore CNH rate) came close to 6.7, and is not too far away from the 6.8 level that was bandied about last week as the PBOC’s possible target for 2016.* The dollar is—broadly speaking—close to unchanged from the time China announced that it would manage its currency with reference to a basket in the middle of December.* So the yuan might be expected to be, very roughly, where it was last December 11. December 11 of course is the day that China released the China Foreign Exchange Trade System (CFETS) basket. Yet since December 11, the yuan is down around 1.5% against the dollar, down about 5 percent against the euro and down nearly 19 percent against the yen. The reason why the renminbi is down against all the major currencies, obviously, is that managing the renminbi "with reference to a basket" hasn’t meant targeting stability against a basket. As the chart above illustrates, over the last seven months the renminbi has slowly depreciated against the CFETS basket. The renminbi has now depreciated by about 5 percent against the CFETS basket since last December, and by about 10 percent since last summer. How? No doubt there are many tricks up the PBOC’s sleeve. But one is straightforward. When the dollar goes down, China hasn’t appreciated its currency by all that much against the dollar. And when the dollar goes up, China has depreciated against the dollar in a way that is consistent with management “with reference to a basket.” That takes advantage of the fact that the yuan’s value against the dollar is what matters inside China, while the broader basket matters more for trade. And it takes advantage of the fact that politically the yuan-to-dollar exchange rate matters more than the yuan-to-euro exchange rate. So even if the yuan was a bit overvalued last summer, it isn’t obviously overvalued now. China’s manufacturing export surplus remains quite large. And export volume growth—which was falling last summer—has now turned around. It is not realistic for Chinese export volumes to outperform global trade by all that much any more; China is simply too big a player in global trade. China will have to adjust to a new normal here. My hope is that China will pocket the depreciation achieved over the last several months, and will now start managing its currency more symmetrically or even be somewhat more willing to allow a stronger dollar to flow through to a stronger yuan. Since January, the expectation of stability (more or less) against the dollar together with the repayment of (unhedged) external debt, a tightening of controls and the threat of intervention in the offshore market seem to have reduced outflow pressures. The fairly steady depreciation against the basket has coincided with smaller reserve sales.*** But there is a risk that speculative pressure could return if the market concludes that China thinks it can now depreciate against a basket thanks to tighter controls and less external debt. And, obviously, if depreciation against the basket can only be achieved through depreciation against the dollar, it is hard to see how the yuan doesn’t become even more of a domestic political issue in the United States. 6.8 against the dollar brings the renminbi back to its level of eight years ago, more or less. * Reuters: "China’s central bank would tolerate a fall in the yuan to as low as 6.8 per dollar in 2016 to support the economy, which would mean the currency matching last year’s record decline of 4.5 percent, policy sources said." The PBOC indirectly pushed back against the story, and has reiterated that it is committed to a "basically stable" renminbi. The Reuters story can also be read two ways: as a signal that China wants a steady depreciation against the dollar, or a signal that there is a limit on how far China is willing to allow the yuan to depreciate against the dollar even if the dollar starts to appreciate against the majors. ** China’s basket doesn’t mirror the U.S. basket. Japan for example, has a 15 percent weight in China’s basket versus a 6-7 percent weight in the Federal Reserve’s broad index, and Canada and Mexico figure more prominently in the U.S. index. The pound, incidentally, has a 4 percent weight in the CFETS basket. Still, the dollar index provides a rough guide to how China would move if it pegged to the dollar. *** Goldman’s Asia team has suggested that Chinese firms have been settling imports with renminbi in 2016, and this flow likely reflects an orchestrated attempt to limit pressure on the currency that should be counted as a form of hidden intervention. I will take that argument up at a later time. But even with the Goldman adjustment, the pace of reserve sales (using the settlement data) has fallen from $100-150 billion a month in January to $25 billion or so in April and May.

-

Post-BrexitA few thoughts, focusing on narrow issues of macroeconomic management rather than the bigger political issues. The United Kingdom has been running a sizeable current account deficit for some time now, thanks to an unusually low national savings rate. That means, on net, it has been supplying the rest of Europe with demand—something other European countries need. This isn’t likely to provide Britain the negotiating leverage the Brexiters claimed (the other European countries fear the precedent more than the loss of demand) but it will shape the economic fallout. The fall in the pound is a necessary part of the United Kingdom’s adjustment. It will spread the pain from a downturn in British demand to the eurozone. Brexit uncertainty is thus a sizable negative shock to growth in Britian’s eurozone trading partners not just to Britain itself: relative to the pre-Brexit referendum baseline, I would guess that Brexit uncertainty will knock a cumulative half a percentage point off eurozone growth over the next two years.* Of course, the eurozone, which runs a significant current account surplus and can borrow at low nominal rates, has the fiscal capacity to counteract this shock. Germany is being paid to borrow for ten years, and the average ten-year rate for the eurozone as a whole is around 1 percent. The eurozone could provide a fiscal offset, whether jointly, through new eurozone investment funds or simply through a shift in say German policy on public investment and other adjustments to national policy. I say this knowing full-well the political constraints to fiscal action. The Germans do not want to run a deficit. The Dutch are committed to bringing an already low deficit down further. France, Italy, and especially Spain face pressure from the commission to tighten policy. The Juncker plan never really created the capacity for shared funding of investment. The eurozone’s aggregate fiscal stance is, more or less, the sum of national fiscal policies of the biggest eurozone economies. If I had to bet, I would bet that the eurozone’s aggregate fiscal impulse will be negative in 2017—exactly the opposite of what it should be when a surplus region is faced with a shock to external demand. A lot depends on the fiscal path Spain negotiates once it forms a new government, given that is running the largest fiscal deficit of the eurozone’s big five economies. Economically, the eurozone would also benefit from additional focus on the enduring overhang of private debt, and the nonperforming loans (NPLs) that continue to clog the arteries of credit. Debt overhangs in the private sector—Dutch mortgage debt, Portuguese corporate debt, Italian small-business loans—are one reason why eurozone demand growth has lagged. Eurozone banks should have been recapitalized years ago, with public money if needed, to allow more scope for the write down of private debt. But in critical countries they were not, even with the impetus from various stress tests and the move toward (limited) banking union. And Europe’s new banking rules are now creating additional incentives for delay. The banking rules require bail-ins, which are typically better politics than outright bailouts. But countries such as Italy are caught in a bind: • Clearing away legacy NPLs takes capital—capital many of its banks do not have; • National governments cannot provide public capital without bailing in a portion of the banks’ liabilities structure; • And in Spain, Portugal and Italy, many of the banks that need capital now have raised capital in the past by selling preferred equity and subordinated debt to their own depositors, so bail-ins in effect mean hitting small investors who took on a set of risks they didn’t understand (and often made investments before the banking rules were tightened). The consensus VoXEU document alluded to this problem, but didn’t quite spell out how the current banking rules could be “credibly modified.” Putting public funds into the banks does not address popular concerns about the way the global economy works. Forcing retail investors to take losses in the name of new European rules does not obviously build public support for “more” Europe. Keeping bad loans at inflated marks on the balance sheet of weak banks undermines new lending, and makes it hard for private demand growth to offset the impact of fiscal consolidation. There is no cost-free option, economically or politically. The eurozone’s ongoing banking issues highlight the broader tensions created by a conception of the eurozone that focuses on the application of common rules with only modest sharing of fiscal risks—and by a political process that has often designed those rules a bit too restrictively, with too much deference to Germany’s desire to avoid being stuck with other countries’ bills and too little recognition of the need to allow the member countries to use their own national balance sheets to spur growth. Something will need to give, eventually. * My back-of-the envelope estimate is close to Draghi’s estimate, and similar to that of Goldman. The OECD’s estimate actually suggests a slightly bigger impact on the eurozone from a similar to slighter larger fall in British output. In their model, the eurozone is facing a two-year drag on growth of about a percentage point; see p. 22.

-

Hard to Pay for Imports Without Exports (BRICS Trade Contraction)Over the past twenty years, the biggest shocks to the global economy have come from sharp swings in financial flows: Asia; the subprime crisis and the run out of shadow banks in the United States and Europe; and the euro area crisis. All forced dramatic changes in trade flows. Emerging Asia went from running a deficit to a surplus back in 1997. The global crisis led to a significant fall in the U.S. external deficit. The euro area crisis led to the disappearance of current account deficits in the euro area’s periphery. And one risk from Brexit is that it would cause funding for the U.K.’s current account deficit to dry up, and force upfront adjustment. The biggest shock to the global economy right now though has come not from last summer’s surge in private capital outflows from China, large as the swing has been,* but rather from an old fashioned terms-of-trade shock. Oil, iron, and copper prices all fell significantly between late 2014 and today. Yes, oil has rebounded from $30, but $50 is not $100 plus. $50 versus $100 oil means the oil-exporters collectively have something like $750 billion-a-year less to spend—either on financial assets, or on imports—than they did a couple of years ago. Add in natural gas and there has been another $100 billion plus fall in export income for the main oil-exporting economies. The fall in traded iron ore prices has had a big impact on Brazil and Australia, but in absolute terms oil’s impact dwarfs that of iron. Brazilian and Australian iron receipts in the balance of payments are down a total of $30 to $40 billion. Big, but not the huge impact of oil. And the old fashioned terms-of-trade shock has had a much bigger global impact than I suspect is commonly realized. Consider a plot of non-oil imports of the “BRICS” (the world’s large emerging economies). The dips in Brazil and Russia in particular are crisis-like. 2015 imports—excluding oil—are down 20 to 30 percent in Brazil and Russia. And both Brazil and Russia are significant economies. A few years back, when their currencies were stronger, their economies were in the $2 to $3 trillion range—only a bit smaller than the British economy. With some notable exceptions, commodity-exporting economies, writ large, have adjusted to the global terms-of-trade shock by reducing their imports rather than by selling assets or increasing their borrowing. A negative terms-of-trade shock implies a fall in trade. A country that cannot get paid what is used to on its exports cannot import (as much). It is a simple point, but still an important one. The adjustment in commodity exporting economies is a very important reason—along with China’s pivot away from imports—why global trade flows have been weak. The BRICS combined GDP is roughly that of the United States, or the full European Union. Their combined non-oil imports fell by a bit over 10 percent in 2015. Excluding commodities, China’s imports in 2015 were down around 8 percent. The non-petrol imports of the other four BRICS were down over 15 percent. To be sure, the data here—the year-over-year change in the trailing 12 month sum—moves slowly. It tells a story about the past, not the present.** The big drops have already taken place. Higher frequency data points to a stabilization. And even though I took petrol out of the data, the data here is nominal. The fall in actual volumes (the "real" data) is a bit smaller, particularly for China. Chinese goods import volumes were down about 2 percent in 2015. Brazil’s goods and services import volumes were down about 15 percent. And Russia’s goods and services import volumes were down about 25 percent. A big change for countries whose real imports on average increased 10 percent a year from 2004 to 2013. *The private financial outflows from China replaced the buildup of official assets, and then were offset by reserve sales. The swing has not forced a major adjustment in China’s exchange rate (to date) or macroeconomic policies (indeed the intensification of outflows was in response to a surprise swing in China’s exchange rate policy rather than vice versa) that led to a big change in China’s trade balance. The rise in China’s surplus in some ways preceded the exchange rate move last August. ** To take an example: the change in the trailing 12 month sum will show a big fall in the U.S. petrol import bill. But with U.S. production now dropping, crude imports rising and a near-certain rise in import prices from these lows, the U.S. petrol deficit is almost certainly now starting to rise again. The United States incidentally paid less than $30 a barrel on its imported oil in the first few months of this year.

-

Remarks on Morning in South AfricaThe following text is the entirety of John Campbell’s speech delivered as part of the Department of State’s Ralph J Bunche Library Series, on June 8, 2016. From a certain perspective, South Africa is a mess. Many South Africans are disappointed by the way the country has seemingly squandered its promise as the ‘Rainbow Nation.’ Under the Jacob Zuma presidential administration, the country is treading water with respect to poverty and addressing the lasting consequences of apartheid. Corruption is rife. You can read all about it in the Mail and Guardian or the Daily Maverick. As a person, Jacob Zuma is very far from Nelson Mandela. He is mired in scandal. There was the misuse of public funds on his private house, Nkandla, including a swimming pool billed as a “fire retardant feature.” There is the rape charge. Though he was not convicted, much of the public believes him to be guilty. The public prosecutor may reopen the numerous charges of his personal corruption with respect to arms sales. His cronies, the Gupta brothers, have been meddling with high level government appointments. There is fear that Zuma and the people around him are seeking to undermine South Africa’s model constitution to advance their own financial interests. The general sense of squalor is captured by a joke that is making the rounds. It goes like this: Snow White, Superman, and Pinocchio were out for a walk in the enchanted forest. They saw a sign for a contest for the most beautiful woman in the world. Snow White promptly entered. A half hour later she rejoined her friends and announced she had won – hands down. They walked on and came to another sign, a contest for the strongest man in the world. Superman promptly entered. A half hour later he rejoined his friends and announced he had won, “aced it.” They continued to walk, and came upon a third sign, this time for a contest for the greatest liar in the world. Pinocchio, up to now feeling left out, perked up and announced that with his nose, he would enter and certainly win. A half an hour later he rejoined his friends, who asked how it went. Through his tears of disappointment, Pinocchio could only say, “Who on earth is Jacob Zuma?” Yet, I have written a book with the core argument that despite the corruption and incompetency of the Zuma administration, the country’s democratic institutions are strong enough to weather the current period of poor governance. Just as the United States weathered Richard Nixon in the past, and perhaps will be required to weather another deeply flawed personality in the future, South Africa can weather Jacob Zuma and his cronies. In both countries there is an independent judiciary, a free press, and strong civil society based on the rule of law. The book is called Morning in South Africa. In the spirit of the Tappet Brothers shameless commerce division, the easiest way to get it is on Amazon. The book is aimed at American readers who stopped paying attention to the South African story after the 1994 election and Nelson Mandela’s inauguration. I hope to bring them up to speed on what has happened since, and to assure them that as rocky as things might appear now, the country’s “deeper truths and better angels,” in Simon Barber’s words, remain intact. Politically the country is a fully functioning democracy with among the best protections of human rights in the world. Morning in South Africa, the title, recalls the theme Ronald Reagan used for his re-election campaign in 1984, “it’s morning in America.” Which, if you were black and poor, or a union organizer, or an anti-apartheid activist, it certainly was not. Nonetheless, Reagan’s optimism was infectious and the slogan did reflect a broader national reality. What with Watergate, defeat in Vietnam, stagflation, energy shortages and the Iran hostage crisis, the ‘70s had been difficult. Relatively speaking, things were looking up at the end of Reagan’s first term. I mean the title of the book to capture a similar ambiguity about South Africa; there are grounds for a parallel optimism notwithstanding Jacob Zuma and the slow pace of economic and social change since the end of apartheid. The book opens with an orientation to the history of South Africa and certain of its parallels to that of the American south. A review of current demographic trends highlights the persistent consequences of white supremacy and apartheid. Whites continue to have much longer life spans than everybody else, a reflection of their access to better education and health services. For whites, it is about the same as in Israel or Russia; f or blacks, in Nigeria or Cameroon. The book includes a discussion of education, health, contemporary politics, and land reform with an eye as to how South Africa’s democracy is responding to thorny challenges. The book highlights the strength of constitutionally mandated institutions, the rule of law, and the independence of the judiciary. South Africa is a constitutional democracy, not a parliamentary democracy. The constitution limits what governments can do at all levels and has among the most elaborate protections of human rights of any country in the world. It is a check on the African National Congress’s (ANC) huge parliamentary majority and frustrates Zuma. Notably, South Africa has outlawed capital punishment and is the only African country that permits gay marriage. Both are the result of judicial rulings based on human rights provision in the constitution. Both are deeply unpopular. But such is the popular respect for the constitution that there has been no significant effort to amend it to permit the first and ban the second. Despite current pessimism, there is little that is new about South Africa’s root challenges. They include the consequences of apartheid and pandemic disease, especially HIV/AIDS. Corruption is not new. It was a characteristic of the apartheid state. The current gloom, the depth of which is new, owes much to the slow economic recovery from the worldwide slump of 2008, the effect of falling commodity prices, and discontent with President Jacob Zuma’s style of governance. Nevertheless, post-apartheid South Africa is stalled, not broken. The highly respected Ibrahim Index of African Governance for 2015 places South Africa at the top of its five analytical categories: safety, rule of law, human rights, economic opportunity, and human development. The only states that it rates higher are small and relatively wealthy, such as Mauritius, Botswana, and Cape Verde. But like other developing countries, South Africa is characterized by gross inequality of income and wealth, but even more so. South Africa has the highest Gini coefficient of any country in the world. There is a small minority of rich people and a huge majority of poor people. But, a generation after apartheid, in South Africa, economic and social inequality is still largely along racial lines. To cite two examples: The gulf between white wealth and that of everybody else is greater now than it was in 1994. In other words, whites are richer now relative to everybody else than they were during the last days of apartheid. On the other hand, male unemployment in the black townships approaches 50 percent. Such realities help account for the ANC’s – and Zuma’s – electoral success. They also drive irresponsible political movements such as Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters. Yet, in the face of current scandals, it is easy to lose sight of how much the ANC governments of Mandela, Mbeki and Zuma have accomplished since 1994. The institutional and ideological props of white supremacy are gone. In education, the ANC government has rationalized and deracialized the nineteen different systems inherited from apartheid. In public health, under Zuma, there has been a turn for the better with respect to HIV/AIDS, perhaps his signature accomplishment as president. The ANC government has established a safety net of allowances that has cut in half the numbers of the very poor. There are about 17 million beneficiaries, out of a population of about 50 million. Beneficiaries are mostly children, the elderly, the sick, and the disabled. Social allowances are about 4 percent of GDP, judged sustainable indefinitely if growth is 3 percent or better, as it usually was from 1994 to 2008. Government economic policy has promoted the growth of a black middle class. There is a political consensus over a National Development Plan that provides a blueprint for economic growth and reform of education and public health. Electoral democracy is strong. The country has conducted credible national elections in 1994, 1999, 2004, 2009, and 2014. In addition, there have been four, also credible, local government elections nationwide, with another coming up this August. The Economist Democracy Index in 2012 rated the quality of South African elections as only slightly below those of Japan and the United States. Democracy as a form of governance in South Africa remains popular. An Afrobarometer poll showed that 72 percent of the respondents were committed to constitutional democracy, 11 percent were indifferent, and 15 percent held that nondemocratic methods are sometimes preferable. Since 1994, South Africa has been a functioning democracy conducted according to the rule of law, largely—though not completely—without legal reference to race even if social and economic change has been slow and incomplete. Ownership of the economy continues to be dominated by whites, now joined by well-connected blacks, but the “face” of South Africa, ranging from television presenters to post office clerks, reflects the country’s racial demographics. Blacks are present in elite institutions ranging from formerly all-white universities to hospitals and country clubs, though by no means in proportion to their share of the population. Nevertheless, black Africans are no longer strangers in their own country. Earlier in my remarks I observed that South Africa has a developed democratic culture. What did I mean? Let me provide an example. The contentious issue of land redistribution from whites to blacks illustrates the strength of the rule of law. At least 80 percent of the population across all racial lines believes that it should be done, but strictly according to the law. Blacks much more than other racial groups believe that whites are due no compensation for their property that the state redistributes. But they, too, affirm that any such distribution must be governed by the law. And the constitution –especially sacred to many blacks because it ended apartheid – recognizes private property. There are signs that many in the ruling ANC power structure have determined that Jacob Zuma must go. It remains to be seen whether South Africans will demand inclusive leadership in the model of Nelson Mandela that would address the needs of the majority population without compromising the country’s democratic institutions. Nevertheless, the argument here is that thanks to the strength of its democratic culture and institutions, the odds are good that South Africa will meet successfully its current challenges. How to account for South Africa’s positive trajectory? Part of the answer is history. South Africa as a limited democracy dates from 1911. That year only white males had the right to vote. White women gained the suffrage in 1939, and then all races and genders in 1994. In 1994, democracy was extended to hitherto excluded parts of the population. But, it did not have to be invented out of whole cloth. Similarly the independence of judiciary dates from the periods of Dutch and British rule and was maintained during the darkest days of apartheid. Democracy and the rule of law have become indigenous to South Africa. A final word about the bilateral relationship. The United States and South Africa share democratic commonalities and the historical experience of white supremacy and its consequences. That would seem to be a good foundation for a special diplomatic relationship. At the time of the 1994 transition, many in the Clinton administration anticipated that future bilateral ties between the two multiracial democracies would be close, exceptional, and mutually beneficial. However, almost a generation later, the official relationship is correct, barely cordial, and hardly special. Moreover, the likelihood is remote of a close partnership anytime soon. In February, the ANC Secretary General Mantashe accused the American embassy in Pretoria of plotting “regime change” – by means of the Young African Leaders Initiative. In fact, the Embassy had consulted with Mantashe, along with others on South African nominees for the program. What happened? One answer is the relative absence of shared diplomatic goals or common security concerns. This reality mitigates against a close partnership. Economic links, while not trivial, were not important enough to overcome the lack of shared security goals. At a deeper level, back to history. History, and often the distorted memory of that history, has been a brake. South Africa and the United States were allies during World War I, World War II, and during the Cold War. Jan Smuts and Woodrow Wilson were close collaborators in the creation of the League of Nations. But, those now in power in Pretoria regard the South African governments that participated in those struggles as at best “colonial” and fundamentally racist. Both Smuts and Wilson are at present condemned as personal racists. Hence, many in the ANC view these wartime alliances with ambiguity if not distaste. For former freedom fighters, there is little history of a community of interest between South Africa and the United States. A consequence is that our bilateral relationship is much closer with, say, Nigeria, than with South Africa. A warming of the official, bilateral relationship will probably have to wait for a generational change within the ANC. Meanwhile, however, the myriad other links between the United states and South Africa, ranging from the economic to the cultural to the scientific to the artistic to mutual tourism are going from strength to strength. The bilateral relationship is more than Jacob Zuma.

-

The Leak in China’s Controls From Hong Kong Imports Is Still SmallThe jump in China’s imports from Hong Kong has generated a bit of attention recently. Monthly imports have gone from around $1 billion this time last year to around $3 billion. It is very reasonable to think that this rise reflects a new way of getting money out of China, rather than a change in the underlying pattern of trade. But plots showing that imports have risen by a some crazy percent miss something important. The magnitudes of the over-invoiced imports are still small. Annualized, the $2 billion monthly difference is about $25 billion. The likely over-invoicing of imports through Hong Kong is also still significantly smaller than the over-invoicing of exports through Hong Kong back in late 2012 and early 2013. In March 2013, exports to Hong Kong were almost $25 billion higher than in March 2012, and first quarter 2013 exports to Hong Kong were up almost $50 billion year-over-year. The implied annual pace of inflows then was close to $200 billion. That was big enough to inflate the overall level of exports in 2013, and thus it had a rather meaningful impact on the year-over-year growth in China’s exports in 2014. And if you are really looking for hidden capital outflows, I personally would focus on the tourism accounts more than goods imports from Hong Kong. Imports of travel services rose by about $100 billion in 2014, jumping $128 billion in 2013 to $236 billion in 2014.* The 85 percent annual rise in travel spending reported in the 2014 balance of payments far exceeded the at-most 20 percent increase in the number of Chinese tourists** travelling abroad. Travel imports jumped another $50 billion in 2015 to $292 billion—real money, and a two-year increase of well over 100 percent. Bottom line: the recent rise in imports through Hong Kong is worth watching, but not yet of a scale that will challenge’s China’s current foreign exchange policy. * These numbers have been heavily revised over time. They may shift again. I didn’t save the data, but I think much of the 2014 jump used to only appear in 2015. ** A November 2015 Goldman Sachs research piece has a 2014 increase in outward tourism of closer to 10 percent, with a total for outward tourists of closer to 110 million.

Online Store

Online Store