Sub-Saharan Africa

Somalia

-

India’s COVID-19 Surge, Somalia’s Political Crisis, and MoreIndia struggles with the world’s largest COVID-19 surge, Somalia’s president addresses Parliament after dropping a bid to extend his term, and the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan gets underway ten years after the raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

-

Somalia's Political Crisis Demands Sustained AttentionWhile international attention has been focused on Ethiopia’s multiple internal and foreign policy crises, the political situation in Somalia has gone from precarious to untenable.

-

Nonstate Warfare

![]() Stephen Biddle explains how nonstate military strategies overturn traditional perspectives on warfare.

Stephen Biddle explains how nonstate military strategies overturn traditional perspectives on warfare.

-

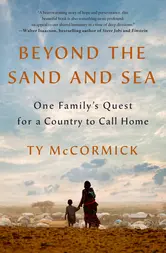

Beyond the Sand and Sea

![]() From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home.

From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home. -

Somali Stability Depends on More Than Just CounterterrorismAmong the Trump administration's many eleventh hour decisions that will require quick review by President Biden’s team was the choice to withdraw nearly all U.S. military personnel from Somalia.

-

From Separatism to Salafism: Militancy on the Swahili CoastNolan Quinn is a research associate for the Council on Foreign Relations’ Africa Program. The revelation that a Kenyan member of al-Shabab was charged with planning a 9/11-style attack on the United States has served to underline the Somali terror group’s enduring presence in East Africa and the region’s continuing relevance to U.S. national security. Shabab has terrorized the northern reaches of the Swahili Coast, which runs from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique, for well over a decade. More recently, a brutal jihadi insurgency has emerged on the Swahili Coast’s southern tip. Ansar al-Sunna (ASWJ), known among other names as Swahili Sunna, ramped up its violent activities in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province in 2017 before spreading more recently into Tanzania. The risk of a further rise in jihadism along the Swahili Coast is serious—and growing. The Swahili Coast has long been recognized as having a rich, eclectic culture shaped by interactions with predominantly Arab traders. (Much of the coast once fell under the rule of the Sultan of Oman.) The region has been strongly influenced by Islam, in contrast to the Great Lakes region further west, which is predominantly Christian. Additionally, much of the mainland is dominated by Bantu ethnic groups, while many coastal residents maintain an identity distinct from their continental peers. As in much of Africa, arbitrary borders drawn during the period of European colonialism separate the region, lumping coastal and mainland residents together across several states. The separation of the Swahili Coast laid the foundations for a re-emergence of pre-independence feelings of marginalization. Many coastal residents, who chafe at government institutions and economic policies seen as favoring Christians and wabara (“people of the mainland”), have called for decentralization of power and even secession from their respective states. Separatist fervor—particularly strong in the Mombasa-Zanzibar corridor—has been stoked by groups such as the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC) and Uamsho (“awakening” in Kiswahili). While both have been defunct or dormant following crackdowns on their leadership, a purported effort to reinvigorate the MRC—already met with a spate of arrests by Kenyan police—illustrates that discontent is still very much present along the coast. In this context, the growing popularity of Salafist ideology in East Africa is worrying. The trend, facilitated by the historical exchange of people and ideas with other littoral states in Africa and the Middle East, has resulted in the displacement of the tolerant, Sufi-inspired Islam that has long been predominant on the Swahili Coast. Salafis’ strict textualist approach raises several objections to Sufism that have been used to motivate attacks by ASWJ in northern Mozambique [PDF] and al-Shabab in Somalia. Less violent—but still occasionally violent—Sufi-Salafi competition has also been on the rise in Tanzania. Several factors suggest that disgruntled wapwani (“people of the coast”), especially youth, are at increased risk of Salafi radicalization. To start, unemployment is widespread on the coast. Joblessness is concentrated among youth and the well-educated—the demographics that have most enthusiastically subscribed to Salafist teachings globally. In Cabo Delgado, ASWJ fighters have clashed with Sufi elders seen as heretical by the Salafi-jihadi group. Yet financial rewards [PDF], such as small loans to start a business or pay bride prices, also appear to be important recruitment incentives. While al-Shabab and ASWJ have gained international notoriety for their insurgent activities, allied groups focusing on youth recruitment in East Africa play a sinister role in enabling their success. Islamist groups such as the Muslim Youth Centre (MYC)—later renamed al-Hijra—in Kenya and the Ansaar Muslim Youth Center (AMYC) in Tanzania have both sent fighters to Somalia and offered refuge [PDF] to returning jihadis. And in Tanga—the coastal region of Tanzania where AMYC was founded and reports [PDF] of small-scale attacks by Islamists have occasionally surfaced—police have in the past uncovered Shabab-linked child indoctrination camps. Swahili’s function as a lingua franca in East Africa is also helping Islamist groups grow in the region. MYC leader Aboud Rogo Mohammed, a radical Kenyan imam who was sanctioned by the United Nations for his support of al-Shabab, targeted Swahili speakers with his repeated calls for the formation of a caliphate in East Africa. Tapes of Rogo preaching in Swahili allowed disaffected youth in Cabo Delgado—many of whom speak Swahili but have a weak or no understanding of Arabic—to access extremist viewpoints, accelerating their radicalization. The jihadis now take advantage of Cabo Delgado’s linguistic, cultural, and business links to coastal communities—in Tanzania in particular—to recruit and expand ASWJ’s operations. Meanwhile, al-Shabab and the Islamic State group, to which ASWJ has been formally aligned since June 2019, utilize Swahili in original and translated media publications. Many of the responses to such activities have been counterproductive. Between 2012 and 2014, Rogo and two of his successors were killed in three separate, extrajudicial shootings blamed on Kenyan police. The killings caused riots in Mombasa, and Rogo’s posthumous influence points to the futility of a “whack-a-mole” approach that tries to silence firebrands. Several mosques and homes in Mombasa were also controversially raided, with hundreds arrested. Yet according to the International Crisis Group (ICG), a shift in strategy since 2015 from heavy-handed policing to community outreach has successfully reduced jihadi recruitment along the Kenyan coast. Tanzania and Mozambique, however, appear to be repeating Kenyan mistakes. The overly militarized response to ASWJ has failed to quell a fast-intensifying insurgency. And in Zanzibar, where some researchers have argued electoral competition has forestalled Salafis’ embrace of jihadism—despite Uamsho’s evolution from religious charity to secessionist movement to nascent militant Islamist group—worsening repression and the ongoing detention of Uamsho leaders ensure the situation remains volatile. Even mainland Tanzania, seen as more pacific than Zanzibar, has seen a recent uptick [PDF] in terrorist violence; Tanzanian security forces, according to ICG, have responded with arbitrary arrests and forced disappearances of coastal Muslims. The threat of rising support for Islamist militancy in East Africa should not take away from efforts to address calls for secession: separatist movements can, of course, turn violent. However, in areas where separatism is rife, ham-fisted clampdowns on Muslim preachers and their followers risk strengthening radicals’ hand. As UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres—speaking in Nairobi—warned, the “final tipping point” to radicalism is often state-led violence and abuse of power. A shift from separatism to endemic radical Salafism would re-frame narratives of coastal exclusion along more explicitly religious lines, causing new problems for governments. While calls for autonomy and independence draw strongly on questions of identity, they remain political—and therefore open to conversation and compromise. A growing Islamist movement, meanwhile, would recast such debates in rigid, ideological terms, thus giving rise to a zero-sum scenario in which dialogue is nigh on impossible.

-

Diplomatic Progress in SomaliaThe re-opening of the U.S. Embassy in Mogadishu, Somalia, is welcome news to many who have worked on U.S. policy issues in the Horn of Africa for decades. It represents not just a positive step in strengthening bilateral relations, but also a victory over those who would prioritize risk-aversion ahead of the actual work of diplomacy, which requires presence, relationships, and a multilayered understanding of the political and social dynamics that shape decision-making for partners on the ground. Achieving thoughtful policy goals in a climate as fractured and fragile as Somalia’s is a difficult task under the best of circumstances. Trying to do it from afar is nearly impossible. But this good news comes at a difficult time. Somalia’s slow and unsteady recovery from total collapse has long been threatened by al-Shabaab, the terrorist organization that still controls significant territory and has the capacity to strike targets in the capital and throughout much of the country, most recently a military base where the U.S. military trains Somali forces. These days, progress in Somalia is also threatened by external powers exporting their rivalries to the Horn. The rift in the Gulf Cooperation Council has found expression in Somalia, where the United Arab Emirates has aggressively courted Somaliland and semi-autonomous Puntland, while Qatar and Turkey are important supporters of President Farmajo’s Somali Federal Government. Rather than uniting Somalis in cooperatively resisting al-Shabaab and building enduring arrangements to provide security and opportunity to the population, this dynamic risks shifting focus to core-periphery tensions that need not be sources of instability for the Somali people. Any country seeking to influence events in Somalia would do well to pay close attention to important lessons from history. The proxy conflict in the Horn during the Cold War empowered corrupt and abusive leaders, led to tremendous human loss and suffering in the region, distorted institutions, poisoned regional relationships, and spawned new threats still bedeviling the United States and others. The unintended consequences of using the region as a venue to outflank a rival are not to be lightly dismissed.

-

The Controversy Over U.S. Strikes in SomaliaThe United States has been helping Somalia fight al-Shabab militants for more than a decade, but rights groups say increasing drone strikes are putting civilians at risk.

-

Global Conflict This Week: Negotiating a Truce in YemenDevelopments in conflicts across the world that you might have missed this week.

-

Global Conflict This Week: Elections Delayed in Kandahar ProvinceDevelopments in conflicts across the world that you might have missed this week.

-

Women This Week: Fighting FGMWelcome to “Women Around the World: This Week,” a series that highlights noteworthy news related to women and U.S. foreign policy. This week’s post, covering July 23 to August 4, was compiled with support from Lucia Petty.

-

Global Conflict This Week: Pro-Government Forces Advance in Southwest SyriaDevelopments in conflicts across the world that you might have missed this week.

-

Lessons Learned in Somalia: AMISOM and Contemporary Peace EnforcementHow can the details of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) shed light on the major questions about peace enforcement missions and the international partnerships that underpin them?

-

An Uptick in Somali Piracy Caused by a Wave of Poor Maritime Decision-MakingCheryl Strauss Einhorn is the creator of the AREA Method, a decision-making system for individuals and companies to solve complex problems. Cheryl is the founder of CSE Consulting and the author of the book Problem Solved, a Powerful System for Making Complex Decisions with Confidence & Conviction. Cheryl teaches as an adjunct professor at Columbia Business School and has won several journalism awards for her investigative stories about international political, business and economic topics. Piracy is on the rise off the coast of Somalia again and there’s evidence that perhaps the maritime industry may have itself to blame. Indeed, the recent Somali hijacking of the Aris 13, a Comoros-flagged fuel tanker belonging to a Greek company, should be a wake-up call to the shipping industry that complacency is dangerous. How so? It seems that the maritime industry is a lot like many of us individually, prone to assumption, judgment, and common cognitive biases including confirmation bias, where we over value information that confirms our existing beliefs and salience bias, where we overweight evidence that is recent and vivid. Back in 2011, piracy was front page news as pirates held crews hostage only to ransom them back for as much as $13 million. The result was that maritime security costs shot up to $7 billion a year as the industry installed extensive security systems including lobbying for and receiving pricey navy patrols, as well as instituting protocols to re-route ships to take longer routes, or, at times increasing ship speed and fuel costs, while at the same time incurring hefty increases in ransom insurance rates. The coordinated vigilance worked. Piracy dropped from a peak of 488 incidents in 2011 to stabilize near 36 incidents each in 2015 and 2016, according to data from Oceans Beyond Piracy (OBP), a nonprofit that studies maritime security. But perhaps the industry misunderstood why piracy rates dropped. Looking at the hard data doesn’t tell the whole story; the industry knows that the numbers are notoriously incomplete. Yes, along with increased security protocols, reporting has improved somewhat, but not much since investigations take time, costing shipping companies up to $1000 per day of lost income, rates of prosecution are low and of course reporting impacts insurance rates, which can jump by 30 percent. Still, industry security costs fell to $1.7 billion in 2016 as the coordinated maritime efforts relaxed. Yes better threat assessments for different kinds of vessels lowered some insurance rates, but even more, the industry’s memory has faded and collective attention to piracy has waned. As incidents dropped, international naval patrols have stopped, partly replaced by intelligence gathering and communication protocols. But security on the seas has now fallen to independent nations like China and Japan. Moreover, private security forces are on the decline in the Indian Ocean. In 2011 private security cost nearly $60,000 per transit. Today rates are lower yet only 34 percent of ships still use armed guards, and even those no longer carry the recommended four-men teams even though “the cost of the guards have come way down,” says Jon Huggins, OBP’s director. In addition to fewer grey vessel patrols and on-board security, shipping companies are taking riskier actions again with regard to speed and proximity to the dangerous Somali coast, even as that country continues to suffer from weak government, warring territories, and ineffective or corrupt policing. The Aris hijacking took place reportedly while the vessel was traveling well below the recommended speed for its location. It was travelling the Socotra Gap, a route between Ethiopia and the island of Socotra in Yemen often used by vessels traveling along the east coast of Africa as a shortcut to save time and money. The pirates have taken note. “Gangs are coming back,” says Huggins, who says that the Aris’s crew was let go allegedly after the pirates emptied a safe on board holding about $70,000. Maybe it’s time for the maritime industry to stop traversing its well-worn mental pathways and to pry open some cognitive space to allow for new information and insight to take hold. Then it might see that it’s mixing up causation and correlation. Piracy didn’t drop because it’s waning. It’s been thwarted by costly and effective international coordination. Vigilance pays and as William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

-

Return of Somali Pirates Alerts PentagonThis is a guest post by Michael Clyne. Michael is a risk management consultant specializing in Africa. You can follow him on Twitter at: @mikeclyne. Pirate attacks have returned to the Gulf of Aden, disturbing Somali waters once a hotbed for piracy but which in recent years achieved a remarkable reversal. At least six commercial vessels have been hijacked or attacked in northern Somali waters since March. U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis warned of the new threat during a press conference last week in neighboring Djibouti, where the United States maintains its only semi-permanent military base on the continent. With relatively minor exceptions, the attacks are the region’s first in five years, a lull reached by a combination of international and private security efforts. But that lull eventually became a victim of its own success, with prevention fatiguing after attacks abated. Governments rolled back robust defense operations, eventually relegating them to monitoring and surveillance. Shipping companies followed suit, cutting costs on expensive security guards once hired to arm and defend their vessels. Secretary Mattis’s warning, however, wasn’t aimed at the navies or military policy which once protected Gulf of Aden shipping lanes. Instead, his remarks were in reference to private shipping companies who should pick up the tab, strengthen security, and reconsider arming their vessels. “We want to make sure the industry continues not to be lax,” said General Thomas Waldhauser (head of U.S. Africa Command), as he re-enforced Secretary Mattis’s position. Yet the drivers of piracy are decidedly international. General Waldhauser attributed the re-emergent attacks to the drought parching the Horn of Africa and famine looming over Somalia, just as the war-ravaged nation enters its “lean season.” Before famine, the modus operandi of Somali pirates had been hijackings-for-ransom, with crewmembers held hostage for months – even years – as their captors negotiated lucrative ransoms. However, without the luxury of time, some recent attacks have skipped drawn-out negotiations to loot cargo in a sign of Somalia’s desperation and resource crunch. This is all despite gradual gains in Somali governance and development, with historic February elections inaugurating a new federal government and attracting foreign capital. However, extremist group al-Shabaab still controls most of Somalia’s vast hinterland where it stands to exploit the famine and drive more unemployed youth toward the sea. President Trump has refocused on Somalia, expanding U.S. military authority to strike al-Shabaab, but traditional counterterrorism operations will do little to prevent piracy, whose networks remain generally distinct from al-Shabaab’s, and may even exacerbate the famine and violence piracy thrives in. Another international driver behind Somalia’s piracy is the overfishing and depletion of Somali waters. Last week’s New York Times exposé of China’s outsized impact on seafood resources focused on West Africa, where China's deep-sea vessels now catch most of their fish. But that’s because a global free-for-all already depleted Somalia’s waters, where corrupt governments continue selling off what’s left. Somalis arrested for piracy often say they are actually fishermen forced to enter shipping lanes from depleted coastal waters. That is rarely true – fishing doesn’t require the AK-47s suspects are caught with – but their excuses do reveal the international dilemma at the heart of piracy. General Waldhauser indicated that he is not ready to conclude that Somali piracy is trending back. But with famine and drought exacerbating its drivers amid a vacuum of deterrence, solutions could be as complex as the problem, requiring a return to international and private measures.

Online Store

Online Store