Global Economics Monthly: February 2014

Pax Budgetus

February 2014

- Report

Bottom Line: A truce has been declared in our long-lasting fiscal wars, reducing market uncertainty while deferring the long-term entitlement and revenue debate. But Congress still matters for economic policy, and its recent failure to pass International Monetary Fund (IMF) reform legislation undermines U.S. authority abroad while weakening the global capacity to respond to crises.

One of the most striking elements of last week's State of the Union address was the scant reference to the fiscal deficit. A bitter war has been waged over the last three years, with multiple fiscal cliffs, threats of shutdowns (and one real partial shutdown), and enough drama around the debt limit to badly unsettle money markets. Now, the deficit is old news, barely even drawing a Republican comment.

More on:

At the same time, the dysfunctional relationship between Congress and the Obama administration was on full display recently with the Hill's failure to approve an IMF-reform package that would strengthen the institution and U.S. influence on international economic issues. Fortunately, Congress will have other chances to get this right by attaching the legislation to must-pass bills, but success will require a stronger political effort from the administration, backed by a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers and business leaders.

A Changing Political Landscape

In a speech that he gave in December on income inequality, President Barack Obama declared: "When it comes to our budget, we should not be stuck in a stale debate from two years ago or three years ago… A relentlessly growing deficit of opportunity is a bigger threat to our future than our rapidly shrinking fiscal deficit."

This shift in priorities was reflected in the recent passage of the $1.1 trillion omnibus spending bill for fiscal year 2014. For the first time in several years, the government was funded without a last-minute cliffhanger or partial government shutdown, which hopefully heralds a period where fiscal policy risk is not a major driver of market volatility and drag on confidence.

December's bipartisan agreement on an omnibus spending deal marked the start of the truce, but fundamental changes took place as a result of the government shutdown in October 2013, the debt limit showdown, and its aftermath. Economists had argued for some time that confrontations over spending and the debt limit were damaging the economy, but it took a political disaster for politicians to buy into the need for a truce. The next big test will be the debt limit extension. Reflecting the lessened desire for confrontation, it now seems likely that Republicans will not ask for spending cuts equal to the debt limit increase, and will look for small, less consequential concessions. The Obama adminstration claims that a debt limit increase will be needed by late February, but, as I have argued in the past, if the deficit numbers are good, the Treasury may not even need a debt ceiling increase until June or July.

Problem Deferred

More on:

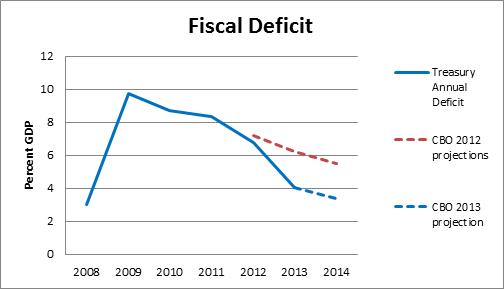

Economic drivers are also constructive for fiscal policy going forward, which is reflected in the substantial improvement in the fiscal deficit. Figure 1 shows that the deficit has fallen more sharply than anticipated in recent years, the fastest rate of decline since World War II. It is now easily financeable at low interest rates and consistent with a forecast for above-trend growth in 2014. Debt has stabilized at around 70 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), and the near-term outlook for the debt has improved with the surprisingly low rate of health care costs. Is that decline permanent? We do not know, but the critical point is that neither the deficit nor the debt looks likely to be a pressing political issue for the next few years. Over the medium term, nearly everyone believes that, as interest rates normalize and the population ages, the deficit and debt will rise and again become pressing policy issues. But that is a problem for another day, and it is hard to imagine that day will come before the 2016 elections.

Figure 1. Fiscal Deficit Is Not the Short-Term Problem It Was Thought to Be

Less Fiscal Risk for Markets, Less Legislation

Fiscal policy is unlikely to be a source of volatility for markets over the next several years. In the context of a monetary policy that appears to be on a slow, steady path toward exiting the extraordinary stimulus measures of the last several years, macro policy will be less of a source of market risk.

At the same time, the reduced urgency of fiscal policy makes fiscal bargains—grand or bland—far less likely. Any new congressional fiscal initiative will need to be paid for, and the pressure to cut these deals will only diminish further as elections approach. Any must-pass legislation—such as a farm or transport bill—will likely be fiscally neutral. Some sort of bipartisan effort on tax reform may still be in play, motivated by the focus on income inequality, but continued Republican opposition to tax hikes would seem to make meaningful reform unlikely.

In that context, fiscal policy news will come mainly from the announcement of administrative measures that can be put into effect without the approval of Congress. In the State of the Union address, the president mentioned the minimum wage, an area where the administration can take a signfiicant steps without congressional approval. There could be further administrative moves in the areas of education, climate change, and efforts to accelerate restructurings of underwater mortgages. All could be material changes in their sectors, but these measures are unlikely to move the dial in terms of their overall effect on growth.

The critical question from a macroeconomic perspective will be whether this reduction in policy uncertainty leads to a pick-up in investment as firms and individuals feel more confident about future prospects. Some recent analysis suggests the uncertainty premium could be on the order of 0.5 to 0.75 percent of GDP. Critics contend that other government policies, such as the Affordable Care Act and Dodd-Frank financial reform, will still be meaningful sources of uncertainty.

The IMF Failure

The limits of our legislative capabilities were on display last month. For all the positives in January's budget agreement, from an international perspective the bill severely disappoints. Left out at the last minute was important IMF reform legislation. Failing to include this package of reforms, agreed to by the Group of Twenty (G20) leaders at the Seoul economic summit in 2010, is a blow to U.S. credibility around the world, and calls into question the ability of the IMF to provide leadership in crisis. Ted Truman has a good blog post on the issue. As he notes, the 2010 Seoul agreement included a doubling of the permanent lending capacity of the IMF and changes in how the Fund's executive board operates that would allow a greater role for rising powers (most importantly China). Politico has a blow-by-blow description of why the legislation was dropped from the omnibus bill. In the end, Republican opposition was reflected in demands for concessions from the Obama administration on unrelated issues of abortion and the tax treatment of advocacy groups. From a congressional perspective, the budgetary cost of the IMF measure was small—$315 million—but the mere fact that an appropriation was needed brought forward opposition from those in Congress unhappy with the IMF's role as a lender of last resort in crises over many decades. Without U.S. congressional ratification, the governance and funding changes can't be completed.

Failure of the legislation does not turn off the lights at the IMF. The Fund currently has a lending capacity of around $400 billion, as a result of special lines (known as New Arrangements to Borrow, or NAB) agreed on in 2009, which could be renewed in event of another crisis. For the foreseeable future, there is no alternative institution to which countries in crisis can turn. However, the failure to pass legislation increases the risk that China and other rising powers will turn away from the IMF and look elsewhere in the event of crisis, creating new institutions or strengthening existing ones (such as the Chiang Mai Initiative, which creates a network of swap lines among Asian countries). The risk is not imminent, but it is a long-run challenge to U.S. influence and effective global governance. Beyond the specific economics, a strengthened IMF enhances global crisis resolution capacity, improving the global financial and trade systems and boosting U.S. influence abroad. U.S. status as a leader of IMF reform is also seriously tarnished.

There are other pieces of must-pass legislation coming up, and the Obama administration should commit to reintroducing the IMF legislation and spending the political capital to get it done. A strong bipartisan push is needed to get this legislation across the finish line.

Looking Ahead: Kahn's take on the news on the horizon

Emerging Markets Turmoil

Recent market turmoil looks overdone and Fed tapering isn't to blame, but emerging markets will continue to differentiate and liquidity likely will remain poor.

Debt Limit Extension?

The U.S. Treasury says it needs a debt limit extension by the end of the month, but may be able to continue until summer without an increase. Republicans don't want a fight.

Europe Quantitative Easing

The European Central Bank continues to resist pressures to ease monetary policy, as lending conditions remain tight ahead of asset-quality review of banks. The Bank should consider purchasing government bonds (quantitative easing) or private periphery assets.

Online Store

Online Store