- Experts

- Securing Ukraine

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

FeaturedExecutive Summary In the decades following World War II, the United States was the undisputed leader of the global economic system. It had the strongest economy in the world and championed a set o…

Report by Matthew P. Goodman and Allison J. Smith March 25, 2025 RealEcon

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedIn recent years, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea have deepened their cooperation, raising concerns about an emerging “Axis of Autocracies” challenging U.S. global leadership. From military suppo…

Virtual Event with Christopher S. Chivvis, Heather Conley, Ivo H. Daalder, Jennifer E. Kavanagh, Tanvi Madan, Ebenezer Obadare, James M. Lindsay, Suzanne Nossel and Laura Trevelyan March 27, 2025

- Related Sites

- More

Economics

Financial Markets

-

World Economic UpdateThis series is presented by the Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies.

-

World Economic UpdateExperts analyze the current state of the global economic system.

-

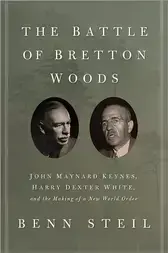

The Battle of Bretton Woods

![]() Read an excerpt of The Battle of Bretton Woods. As World War II drew to a close, representatives from forty-four nations convened in the New Hampshire town of Bretton Woods to design a stable global monetary system. Leading the discussions were John Maynard Keynes, the great economist who was there to find a place for the fading British Empire, and Harry Dexter White, a senior U.S. Treasury official. By the end of the conference, White had outmaneuvered Keynes to establish a global financial framework with the U.S. dollar firmly at its core. How did a little-known American bureaucrat sideline one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century, and how did this determine the course of the postwar world? The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order tells the story of the intertwining lives and events surrounding that historic conference. In a book the Financial Times calls "a triumph of economic and diplomatic history," author Benn Steil, CFR senior fellow and director of international economics, challenges the misconception that the conference was an amiable collaboration. He reveals that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Treasury had an ambitious geopolitical agenda that sought to use the conference as a means to eliminate Great Britain as a rival. Steil also offers a portrait of the complex and controversial White, revealing the motives behind White's clandestine communications with Soviet intelligence officials—to whom he was arguably more important than the famous early–Cold War spy Alger Hiss. "Everything is here: political chicanery, bureaucratic skulduggery, espionage, hard economic detail and the acid humour of men making history under pressure," writes Tony Barber, reviewer for the FT. With calls for a new Bretton Woods following the financial crisis of 2008 and escalating currency wars, the book also offers valuable, practical lessons for policymakers today. A Council on Foreign Relations Book Educators: Access the Teaching Module for The Battle of Bretton Woods.

Read an excerpt of The Battle of Bretton Woods. As World War II drew to a close, representatives from forty-four nations convened in the New Hampshire town of Bretton Woods to design a stable global monetary system. Leading the discussions were John Maynard Keynes, the great economist who was there to find a place for the fading British Empire, and Harry Dexter White, a senior U.S. Treasury official. By the end of the conference, White had outmaneuvered Keynes to establish a global financial framework with the U.S. dollar firmly at its core. How did a little-known American bureaucrat sideline one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century, and how did this determine the course of the postwar world? The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order tells the story of the intertwining lives and events surrounding that historic conference. In a book the Financial Times calls "a triumph of economic and diplomatic history," author Benn Steil, CFR senior fellow and director of international economics, challenges the misconception that the conference was an amiable collaboration. He reveals that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Treasury had an ambitious geopolitical agenda that sought to use the conference as a means to eliminate Great Britain as a rival. Steil also offers a portrait of the complex and controversial White, revealing the motives behind White's clandestine communications with Soviet intelligence officials—to whom he was arguably more important than the famous early–Cold War spy Alger Hiss. "Everything is here: political chicanery, bureaucratic skulduggery, espionage, hard economic detail and the acid humour of men making history under pressure," writes Tony Barber, reviewer for the FT. With calls for a new Bretton Woods following the financial crisis of 2008 and escalating currency wars, the book also offers valuable, practical lessons for policymakers today. A Council on Foreign Relations Book Educators: Access the Teaching Module for The Battle of Bretton Woods.

-

Prospects for the Global Economy in 2013What does 2013 have in store for the global economy? We asked five distinguished experts to identify the most important trends, challenges, and opportunities in the upcoming year.

-

Is Federal Student Debt the Sequel to Housing?Back in March, we showed that the $1.4 trillion in U.S. direct federal student loans that will be outstanding by 2020 will amount to roughly 7.7% of the country’s gross debt. This is 6.3 percentage points higher than it would have been had the scheme not been nationalized in President Obama’s first term. The government’s net debt was not directly affected by the move, as the government acquires assets when it issues student loans. The problem is that projected default rates on such loans have been climbing as the volume issued has increased, as shown in the graphic above. If we apply the projected default rate on loans originated in 2009 to the amount of student loans outstanding in 2012, we find that defaults on federal student loans currently outstanding are likely to cost taxpayers almost $80 billion. And the cost is projected to increase rapidly over the next decade as default rates continue to rise and the amount of student debt the federal government owns soars. There is more than a whiff of resemblance between the rise of the federal government’s student debt liability and the mortgage bubble – the detritus debt of which wound up nationalized. There is little in the way of credit checks carried out, and no evaluation of future earnings prospects. In the ten years to 2008, the amount of mortgage debt tripled: $3.2 trillion to $9.3 trillion. The CBO projects that student loans on the government’s balance sheet will rise just as fast: $453 billion in 2011 to $1.4 trillion in 2020. A 17.3% default rate on $1.4 trillion in loans would cost taxpayers about $240 billion. This is equivalent to 1% of the CBO’s GDP projection for 2020. It is also more than three times the 2013 federal funding level for the Department of Education, and just slightly less than ten times the amount the president requested for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs in his most recent budget. It is surely worth asking, therefore, whether this $240 billion could be used more effectively than it will be in writing off defaulted student loans. Department of Education: Default Rates Bloomberg.com: Student Loans Go Unpaid, Burden U.S. Economy Wall Street Journal: Federal Student Lending Swells Geo-Graphics: Will Student Debt Add to America’s Fiscal Woes?

-

C. Peter McColough Series on International Economics with Vittorio GrilliMinister Grilli will discuss recent economic developments in Italy and the eurozone. The C. Peter McColough Series on International Economics is presented by the Corporate Program and the Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies.

-

A Conversation with Vittorio GrilliVittorio Grilli, Italy's minister of economy and finance, discusses recent economic developments in Italy and the eurozone.

-

Nigerian Finance Minister’s Mother KidnappedKamene Okonjo, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s mother, who is a medical doctor and the wife of a traditional ruler, was kidnapped on December 9, 2012. The kidnapping highlights a growing menace in the oil-rich Niger Delta. Ten heavily armed men kidnapped Professor (Mrs.) Kamene Okonjo, wife of Professor Chukuka Okonjo, the Obi of Ogwashi-Uku, from her home. She is the mother of the Coordinating Minister for the Economy and Minister of Finance, Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala. The victim is eighty-two years old. The Coordinating Minister is unpopular among many Nigerians, so a political motive for the crime cannot be ruled out. But, I think it is unlikely. Kidnapping as a purely criminal enterprise has been on the upswing. Delta state, where the Minister’s mother lives, has been especially plagued with it. Victims are often individuals with the means to pay a ransom. When ransom is paid, the victims are released. Kidnapping of expatriate oil company employees was a widely used tactic by the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) during its insurrection that ended in 2009 with an amnesty program that included payoffs for the warlords. The police are claiming that they are “on top of it” with respect to this high-profile kidnapping. Beyond the hurt and anxiety that this vicious crime is bound to cause the victim’s family, it will also embarrass the Jonathan administration, of which Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is such a prominent member.

-

Greece Hurtles Toward Its Fiscal CliffThe United States marches solemnly towards its fiscal cliff, awaiting only the command from the Goddess of Reason to halt. Unfortunately for Greece, that country plugged its ears back in March. Like the United States, Greece made prior commitments on spending and taxation in order to bind itself to the mission of deficit reduction. Unlike the United States, Greece left itself little means to unbind itself. As shown in the graphic above, its massive debt restructuring in March only reduced its debt-to-GDP ratio from 170% to 150%, but in the process made further significant restructuring much more difficult. Before the March restructuring, Greece owed private sector creditors €177 billion in obligations governed by Greek law and only €30 worth governed by international law, the latter being vastly more difficult to walk away from. After the restructuring, Greece owed private sector creditors only €86 billion, but all of it was now governed by international law (31.5%*177 + 30). And it also added €75 billion to its €124 billion stock of official sector (EU and IMF) obligations, bringing that total to a whopping €200 billion. Though Greece desperately needs to shed more debt, it faces the problem that its private sector creditors are now all shielded by international law, and its public sector creditors are protected by the power to hurl it into unsplendid economic and political isolation. This suggests strongly that Greece should simply have repudiated all its Greek-law private sector debt back in March, when it had the chance. Why didn’t it? Many reasons, some of which flimsy – such as fears of triggering credit default swaps if the restructuring were “involuntary.” But the most pressing reason was to avoid crushing the Greek banking sector, which was exposed to Greek sovereign debt to the tune of about €50 billion. The €25 billion lent to Greece by the so-called European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) in order to recapitalize its banks would then have to have been a much higher €50 billion. Still, Greece would be at considerably less risk of hurtling over the fiscal cliff today had it avoided taking on the additional €56 billion worth of nonrepudiable private sector IOUs in March. In contrast, the United States can avoid its looming cliff by Congress and the president agreeing just to keep on adding to the prodigious national tab. It’s good to be the king of reserve-currency issuers - at least until the market cuts your head off. European Financial Stability Fund: Questions and Answers IMF: Greece's Financial Position in the Fund as of Sept. 30 BIS: Consolidated Banking Statistics Geo-Graphics: The IMF Is Shocked, Shocked at Greece's Fiscal Failure. Should It Be?

-

The Future of Energy InsecurityA massive cyberattack this summer on Saudi Aramco, Riyadh’s energy giant, left some 30,000-plus of the company’s computers lifeless, making a rather futuristic threat to the oil and gas industry front page news. U.S. Secretary of Defenese Leon Panetta called the attack “probably the most destructive…that the business sector has seen to date.” The Saudis weren’t the only targets. RasGas, a Qatari natural gas company, was also hit. Months later, investigators are still trying to get to the bottom of what happened, and more importantly, why it did, and what can stop it from happening again. In a piece for The National Interest, I argue that cyberattacks on oil assets around the world pose a real risk to energy prices, and hence the U.S. economy. They also jeopardize the competitiveness of American firms abroad. It’s an issue where national security and economic well-being meet. And it’s a challenge that’s not going away. The risks of hackers penetrating the country’s electrical grid have been widely discussed for years. Less so what cyber means for oil and gas companies and markets. U.S. officials and the global energy industry have their hands full in coming to terms with this new virtual landscape. Check out the piece here.

-

Democracy in Development: Insurance Innovations for the PoorYesterday on my blog, I wrote about the obstacles that prevent poor people from obtaining insurance—and the innovations that are upending this reality. I focus on Ghana, where the organization MicroEnsure is offering low-cost life insurance tied to mobile phone use and savings accounts. As I explain: Insurance is not something generally available to the poor, who arguably need it most. It is generally viewed as a luxury financial product, and financial institutions have shown little interest in creating insurance products to meet the needs of the poorest. But that is starting to change. You can read the full post here.

-

Obama’s Green Jobs Cost Big BucksPresident Obama is committed to pursuing a “[renewable-energy] strategy that’s cleaner, cheaper, and full of new jobs” (January 24, 2012). He highlighted the job point during the October 16 presidential debate: “I expect those new energy sources to be built right here in the United States. That’s going to help [young graduates] get a job.” Green may be good, but this week’s Geo-Graphic shows that the jobs come at a hefty cost. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that energy-related tax preferences will cost Americans $5.4 billion this year. Half of this, $2.7 billion, will benefit green sectors: $1 billion in nuclear subsidies, $1.3 billion in wind-energy credits for electricity production, and $400 million in solar-energy property credits. So-called “section 1603” renewable energy grants, part of the 2009 fiscal stimulus package, will cost taxpayers a further $5.8 billion. If we assume that the grants are awarded across sectors in the last five months of this year as they were in the first seven, then the nuclear, solar, and wind energy sectors will receive $4 billion of this, boosting total green-sector subsidies to $6.7 billion this year. Taxpayers will also provide $700 million in energy-efficient property credits. The credits apply mainly to solar, though we don’t know the precise allocation – so we leave it out of the figure, which therefore understates the cost of solar-backed jobs. Dividing the total wind, solar, and nuclear subsidies by the number of Americans employed in these sectors (252,000), they are currently generating jobs at an average annual cost to taxpayers of over $29,000. Wind jobs cost taxpayers nearly $47,000 per job per year. By way of comparison, the coal, oil, and gas sectors receive $2.7 billion in subsidies annually, and employ about 1.4 million Americans. The taxpayer-cost per job in these sectors is therefore just over $1,900. The bottom line is that green-energy jobs cost taxpayers, on average, 15 times more than oil, gas, and coal jobs. Wind-backed jobs cost 25 times more. Given the current state of energy-production technology, green jobs don’t come cheap. Romil Chouhan contributed to this post. NYTimes.com: Transcript of the Second Presidential Debate Treasury: Overview and Status Update of the Section 1603 Program Bloomberg.com: U.S. Solar Jobs Face Bright Future, Wind Posts Flutter Foreign Affairs: Tough Love for Renewable Energy

-

Brazil’s New Protectionist MoodWhile a new round of U.S. quantitative easing will have a negative impact on emerging markets like Brazil, the country should not blame U.S. monetary policy for the structural flaws in its economy, says expert Bernardo Wjuniski.

-

There’s a $1 Trillion Hole in Romney’s Budget MathIn last week’s vice-presidential debate, Republican Paul Ryan defended the fiscal prudence of lowering top marginal income tax rates by arguing that it would be accompanied by “forego[ing] about $1.1 trillion in loopholes and deductions . . . deny[ing] those loopholes and deductions to higher-income taxpayers.” The $1.1 trillion he refers to is actually an amalgam of specific “tax expenditures” – benefits distributed through reductions in taxes otherwise owed – identified by the Joint Committee on Taxation. We break out the largest 10 of these graphically in the figure above. The full list is available here: http://subsidyscope.org/data/ The red bars indicate items that Romney and Ryan had previously promised not to touch: exclusion of employer contributions for health care, deductions for mortgage interest, reduced tax rates on dividends and long-term capital gains, and deductions for charitable giving. These four items constitute a massive 30% of the $1.1 trillion. Therefore the Ryan pledge to cut loopholes and deductions cannot, mathematically, be worth more than $770 billion. And note some of the other big-ticket “loopholes and deductions” on the list. Social security and other retirement income constitute three of the top ten items, together making up 13% of the total, and the earned income credit, which benefits the poor, represents another 5% of the total. Would Romney and Ryan eliminate those deductions? We’ll speculate here: no. A quick skim of the remainder shows that few of these items constitute “loopholes” in the public’s mind – they are items few imagine could or should be taxed. In short, Romney and Ryan cannot, logically, keep the pledge to cut $1.1 trillion in tax shields for the rich, because (1) they have already ruled out eliminating the biggest of such shields, and (2) much of the $1.1 trillion is actually derived from tax expenditures targeted at lower and middle income taxpayers – not tax shields for the rich. This almost surely means that only a small fraction of the $1.1 trillion is actually in play. Sensitive to the charge that his numbers are not adding up, Romney proposed at Tuesday night’s presidential debate capping deductions at $25,000. This would raise $1.3 trillion in revenues over the next ten years, according to the Tax Policy Center. But that figure is only slightly above what Ryan said they would raise each year. A $1 trillion a year hole remains in their budget math. Transcript: The 2012 Vice Presidential Debate Pew: Subsidyscope Tax Expenditure Database Romney: Tax Plan Ryan: Sept. 30 Appearance on Fox News Sunday

-

Lessons from Energy HistoryToday the State Department released the thirty-seventh volume of its history of U.S. foreign relations. It’s one that many readers of this blog will find fascinating. “Energy Crisis: 1974-1980” runs 1,004 pages, consisting mostly of previously classified meeting records and memos that give a window into a tumultuous time in U.S. energy history, and one in which many of the roots of our ongoing energy debates were first established. I obviously haven’t had time to read all the way through, but upon skimming, one thing in particular struck me. (If you want the juicy quotes, check out my colleague Micah Zenko’s post.) When we think about the relationship between oil markets and international relations today, one of the most important features we often focus on is the existence of a robust spot market, in which buyers and sellers can come together to discover the “right” price for oil. Spot markets make the geographic origin of any country’s oil far less important than it otherwise would be: If a regular oil source cuts off supplies, the consumer can turn to the spot market for relief. Spot markets therefore help depoliticize the global oil market and provide critical resilience for consumers. In the new State Department history, the words “spot market” only appear once prior to late 1978, but at that point, they start coming up a lot. Unlike today, though, the spot market isn’t seen as a savior – instead, it’s a menace. “Spot market is a small residual market that is not representative of appropriate or market clearing prices,” warns one State Department cable. In May 1979, the Treasury Secretary floats the possibility of an “agreement by the oil-importing counties to boycott the spot market”. That June, the Secretary of State writes that “we will seek to diminish substantially the role of the spot market – and thus bring more order into the world’s oil pricing and marketing system”. Throughout the discussion a consistent theme emerges: spot markets are too vulnerable to speculators, and must thus be suppressed. There are at least two lessons worth taking away from the sharply different view of a critical element of today’s global energy system. The first concerns financial speculators. It’s tough to read the 1970s rhetoric about spot markets without hearing echos of how people talk about oil-related financial markets today, right down to the worries about speculation, lack of transparency, and price distortions, and the potential benefits of reining dangerous markets in. When it came to physical markets, though, the best cure for small and volatile spot markets turned out to be bigger and more liquid ones (along with greater transparency). The same may be true for commodities-related financial markets today: the right cure for whatever problems they currently pose may be a mix of greater scope (rather than new restrictions) along with more transparency. The second lesson is that the current market-based system of assuring energy security was never inevitable or somehow the natural order of things. Instead, it’s a political construct, and one that didn’t come into being easily. It would be unwise to assume without question that it will be around forever.

Online Store

Online Store