What happened to financial globalization?

More on:

Net (private) financial inflows to the US in q1 2007: $466b

Net (private) financial inflows to the US in q2 2007: $552b

Net (private) financial inflows to the US in q3 2007: $238b

Net (private) financial inflows to the US in q4 2007: $195b

Notice a change?

All these numbers are a bit overstayed because they count some official flows as private flows. The 2007 current account data hasn’t been revised to reflect the most recent survey. But the scale of the under-counting didn’t change radically over the course of the year.

Private inflows into the US fell dramatically after August.

Private outflows to the US also fell.

The best explanation for this is the unwinding of the shadow financial system - one that was largely based offshore. A lot of entities (to use the terminology of the shadow financial system) were legally domiciled offshore. However, they were issuing short-term dollar debt to American investors to finance the purchase of long-term US dollar debt. Carlyle Capital is the perfect example. It was legally based in London for tax reasons but managed out of New York, issued short-term dollar debt and held long-term US debt.

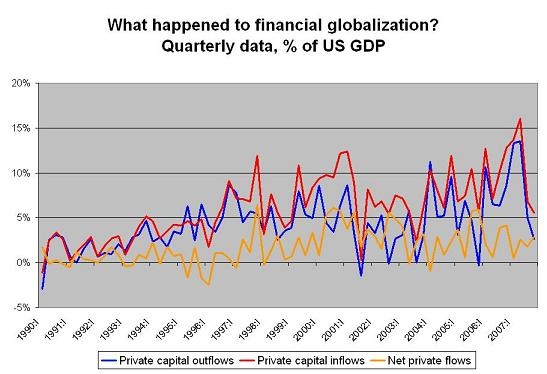

A chart that plots quarterly private inflows and outflows as a share of GDP shows the change.

The chart is noisy, but it still shows that the last time inflows and outflows were this low relative to GDP was in q3 2001. And 9.11 probably had something to do with that data.

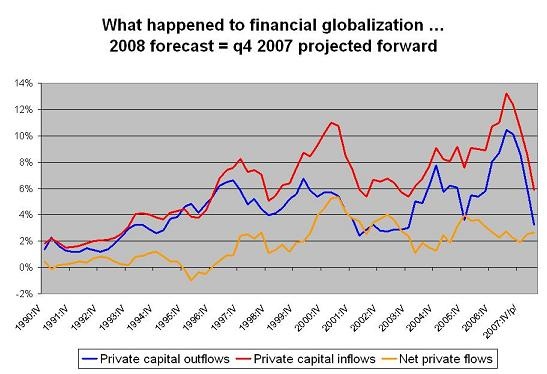

To show how large the shift could be, I assumed that q1 2008 and q2 2008 would be like q4 2007 and plotted the rolling four quarter sums v GDP. A rolling four quarter sum smooths out some of the volatility in the quarterly series; projecting the current fall forward is a way of highlighting just how large the recent fall has been.

Unless something changes and private flows really pick up (and they did not seem to pick up in the January TIC data) "financial globalization" has been scaled down.

Financial globalization, remember, is notion that inflows and outflows are both rising over time, as portfolios become more diversified. This doesn’t necessarily need to lead to current account deficits - as inflows and outflows can match (the eurozone is great example) - but the rise in financial globalization was often cited as a reason why larger current account deficits could be sustained more easily than in the past.

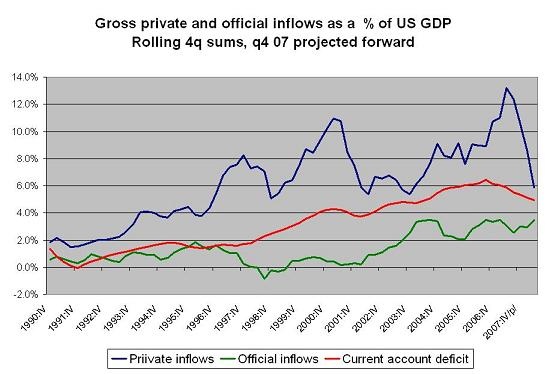

The large scale of private inflows and outflows was also often cited as evidence that official flows weren’t all that large. Sure, official inflows were 3-4% of US GDP and in the absence of any official outflows (the US isn’t building up reserves), net official inflows were large relative to the roughly 6% of GDP US current account deficit (now more like 5%). But, official flows were still small relative to private inflows so, at least the argument went, they weren’t all that important.

The fall in private flows - particularly when official inflows are by all signs rising - changes the equation. Net official flows don’t just provide a large about of the net financing needed to sustain the current account deficit. They also are increasingly large relative to private flows. To highlight recent trends, I projected q4 gross official and gross private inflows forward and plotted the resulting rolling four quarter sum relative to the US current account deficit.

Actually, I think there is a much more fundamental question that should be asked. Was the increase in "financial globalilzation" ever all it was cracked up to be, or was it largely a product of the rise of the "shadow" financial system in London? A huge share of the increase in "financial globalization" stemmed from a rise in short-term flows. I think it largely reflects the "Carlyle capital" effect. Hedge funds and SIVS (mini-credit hedge funds) that sold short-term debt to the US to buy various kinds of US debt but that were offshore for tax reasons. Such entities lead to an increase in offshore claims without any real rise in Americans exposure to the rest of the world.

This isn’t just an academic issue.

If the Fed and others had been asking a few more hard questions about who was behind all the flows going through London over the past few years rather than assuming that they just reflected "financial globalization," they might have gotten a better grip on the scale of the "off-balance" sheet risks that American banks were taking through SIVS and similar structures. After all, it was pretty clear that London was buying a lot of dollar denominated US debt (including a lot of US corporate debt). And it was also clear that these purchases were not "funded" with euros. The currency risk on that trade would have been deadly. The clues were there.

There is a lot of scope for US-UK financial cooperation on these issues.

Understanding the financial flows moving through the UK - and the sources of dollar funding for UK purchasers of dollar assets - is increasingly important to understanding the global financial system. But the US doesn’t seem to want to regulate (the Paulson plan I think assumes that broker-dealers access to the Fed is temporary and won’t be expected in the future, so there is no need for the Fed to regulate their capital and liquidity) and the UK hasn’t shown much willingness to improve the quality of its capital flows data ...

Better capital flows data from the US likely would have shown a large increase in the short-term debt securities UK entities were issuing to US investors over the past few years. That might have changed the way the US was thinking about financial globalization.

Better UK capital flows data also likely would show that UK based financial institutions have received large inflows of dollars from official investors, dollars that have in turn been invested in the US and show up as private inflows in the US data.

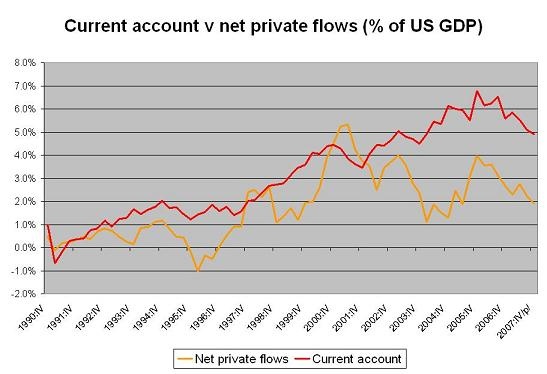

The following chart shows net private flows (gross private inflows - gross outflows) -- as measured by the US quarterly data. Net private flows have been sliding recently.

Once the latest survey data is factored in, the slide in private flows will be larger: official purchases will be revised up and private purchases down. And if the growth in the official money managed in the UK is factored in, the slide would likely be even larger. Most of the Gulf’s money doesn’t show up at all in the US data -- and the Gulf seems determined to hold on to the dollar, no matter the economic cost.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store