January’s TIC data ...

More on:

John Jansen is right; today’s TIC January data was a disaster. $150 billion in (net) capital outflows (-148.9 billion to be precise) cannot sustain even a $40 billion trade deficit.

I also though have learned that the TIC data doesn’t necessarily match the trade deficit on a monthly basis -- and on occasion it moves in ways that seem inconsistent with the market. If the big outflow had come in December (a month when the dollar slid) rather than January, the flow data and the market move would fit together. But a big outflow in January is hard to square with the dollar’s January rally.

Long-term inflows in January were weak -- with net sales of long-term assets by both private and official investors. But that isn’t news. Setting December (when foreign private investors bought a bunch of US corporate bonds) aside, foreign investors haven’t been buying long-term US assets since the crisis hit.

The swing came from two sources:

1) US investors bought a bunch of foreign bonds. That is a change. US investors had been net sellers of foreign bonds and equities through out the fall.

2) Banks stopped piling into US assets. In October -- at the peak of the crisis -- private investors abroad bought $64 billion US t-bills and increased their dollar deposits by $196 billion (see line 29 of the TIC data; "change in banks own (net) dollar-denominated liabilities). In January, credit conditions eased a bit, and private investors reduced their t-bill holds by $44 billion and the banks reduced their (net) dollar deposits by $119 billion.

In some deep sense, the $150 billion outflow in January offsets the $273 billion inflow in October. Over time, the TIC flows do tend to converge with the trade balance.

Incidentally China is still buying Treasuries. It bought $12.2 billion in January, including $11.6b in short-term Treasury bills. It also is still selling Agencies -- its Agency holdings fell by $3.1 b.

Russia also, interestingly, added to its holdings of short-term Treasury bills. The Gulf reduced its dollar deposits (now at $114.3b, down from a peak of $125.5b in November) whether to support its domestic banks or to cover stretched budgets. The Gulf (and Brazil) also bought a decent number of long-term Treasuries. Most official buying, though, came at the short-end. In aggregate, the official sector sold $1.9 billion of long-term Treasuries while adding $29 billion to its short-term bills.

That continues a broader trend. Over the last 12 months official investors added close to $280 billion to their bill portfolio. Average central bank purchases of bills over the last four months were around $50 billion, roughly enought to have covered the trade deficit in the absence of other capital flows.

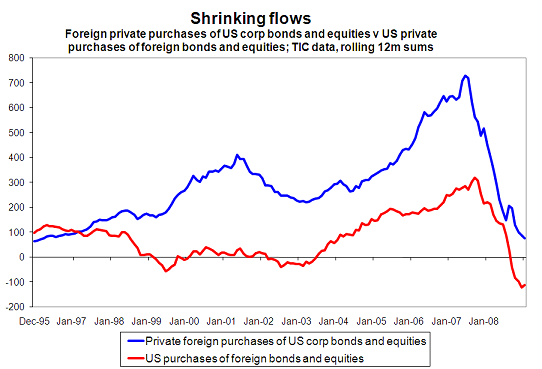

Indeed, the real legacy of the crisis has been an enormous contraction in long-term flows, with a corresponding increase in the United States reliance on short-term financing. And also a shift away from risk assets.

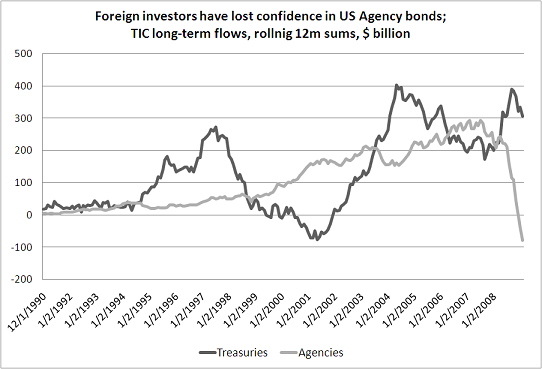

One striking fact is that foreign investors now consider Agencies to be a "risky" asset. Over the last 12ms, foreign investors -- in this case, primarily central banks, as they were the main foreign buyers of Agency bonds -- concluded that the Agencies aren’t a safe long-term store of value.

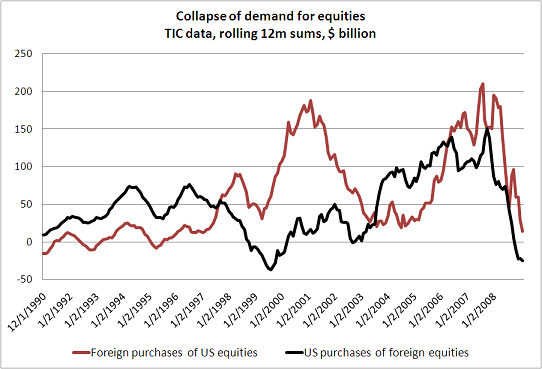

Another is that demand for US equities has disappeared. Over the last 12 months of data, foreign investors have only purchased $24 billion of US equities. The impact of the fall in foreign demand for US equities though has been offset by an equally sharp fall in US demand for global equities. Indeed, Americans have been net sellers of the rest of the world’s stocks over the last 12 months.

One small aside: I strongly suspect that central banks and sovereign funds are responsible for the upward blip in demand for US equities in the middle of 2007. It wasn’t just SAFE either. There was a lot of pressure on all central banks to increase returns on their dollar reserves back when the dollar was falling. Central banks also wanted to show that there was no need to set up a separate sovereign fund to manage equity investments ...

The overall result of the crisis hasn’t been a rise in demand for US assets so much as a large contraction in all flows. The impact of the collapse in foreign demand for US risk assets (corporate bonds, equities) though has been offset by a collapse in US demand for foreign assets. I stripped out known official purchases from the data, but no doubt the data still is influenced by the increase in the official sector’s risk appetite in 2006 and 2007.

It may not be financial deglobalization, but it certainly is a major slowdown in financial globalization.

Krugman believes European economic and financial integration got ahead of European political integration. The same probably can be said of global financial integration.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store