How a US financial crises rebounded to benefit the dollar: three pictures

More on:

How exactly can a financial crisis that started in the US -- and that has hit the US hard -- be good for the dollar?

Part of it is that other countries are now in worse shape that the US; what started as a US crisis turned into a global crisis. Part of it is that a fall in the price of oil is good for the US (lower oil import bill) and seemingly good for the dollar. And part of it is that -- judging from the TIC data -- Americans are selling their foreign investments in "risky" assets faster than foreigners are selling their investments in risky US assets.

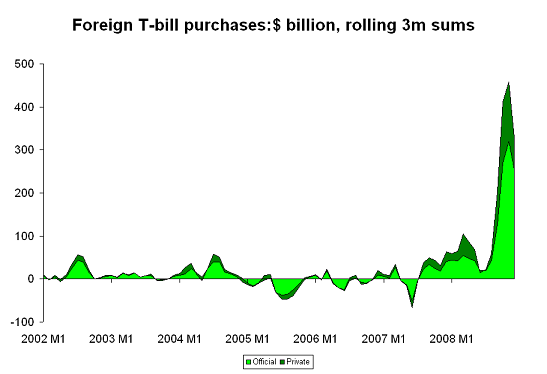

The huge surge in demand for t-bills from central banks and private investors alike hasn’t hurt either.

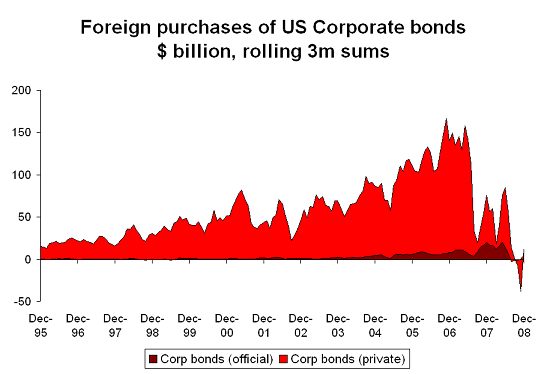

The evidence? To start, there is no real sign that private demand for US corporate bonds has picked up. There was a blip up in the December TIC data. But a rolling 3m sum -- a measure that smooths out a bit of the monthly volatility -- suggests that overall demand for US corporate bonds remains subdued.

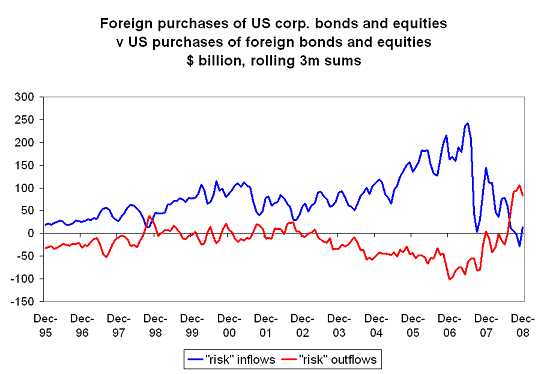

Moreover, what matters for the dollar is foreign demand for US assets relative to US demand for foreign assets. Foreign demand for US corporate bonds and equities remains very weak. Foreigners aren’t therefore providing the flows needed to sustain the dollar (and the US current account deficit) by buying risky US assets. But that doesn’t matter so long as Americans are selling their foreign portfolio. Over the last three months of data (October to December) net sales have generated a flow of close to $100 billion dollars.

And then there is global demand for treasury bills. That soared in the crisis. Call it a dollar shortage among private investors. Or call it a flight by central banks away from anything that hints of credit risk, as Agency sales offset some of the surge in central bank purchases of Treasury bills. But the graph still speaks for itself.

The real question is how long this pattern can persist. The last TIC data point comes from December -- and we are now in March, so the pattern could have changed over the past couple of months. The dollar’s ongoing strength though suggests that there is an underlying supporting flow, and the market’s ongoing distress suggest it hasn’t come from a surge in foreign demand for risky US assets. Setting aside ongoing demand for Treasuries from central banks (the Fed’s custodial holdings have continued to rise) and dollar liquidity-starved investors globally, my guess is that global capital flows are still contracting. They just seem to be contracting in a dollar positive way ...

More on:

Online Store

Online Store