The debate over the pace of hot money flows into China

More on:

Are hot money inflows to China falling? Or rising?

Are hot money flows a constraint on the PBoC’s ability to raise domestic Chinese interest rates to try to curb inflation, or not?

And, more broadly, can China sustain a gradual pace of RMB appreciation? Or even a a gradual pace of appreciation against basket, not just the dollar, as Li Yang has suggested? Or does an expected , gradual appreciation invite unlimited inflows and thus pose impossible-to-solve problems for a "stretched" central bank, leaving only one way out -- a large one-off revaluation?

These are all big questions. And the leading analysts at major banks do not agree on the answers.

Morgan Stanley’s Stephen Jen thinks hot money inflows are picking up. He wrote on Monday:

.. just look at how much capital flowed into China last year (US$200 billion), over and above the large trade surplus (US$260 billion). Much of the former was a result of the expectation of CNY appreciation. I believe that these inflows have accelerated since November, when Beijing moved USD/CNY into overdrive

Jon Anderson of UBS thinks hot money inflows remain contained -- and have actually fallen off their pace of earlier this year. Anderson in a recent report, as quoted by Michael Pettis:

Another very common argument is that can’t successfully pursue a gradual renminbi strategy, since letting the currency appreciate by 8% to 10% per year would bring in a flood of speculative capital and overwhelm the PBC’s ability to control the money supply. And in the first half of 2007, it seemed that this was precisely the case: "hot" money was visibly returning to the mainland once again in large amounts, and the central bank was forced to slow down the pace of exchange rate appreciation so as not to encourage further speculation.

However, over the past six months those pressures have faded. As it turns out, the main driver of capital inflows was not exchange rate expectations but rather the booming equity and property markets.

FX reserve pressures have been fading over the past six months following the "scare" in the first half of 2007, when inflows jumped sharply. The trade surplus was essentially flat through all of last year on a seasonally adjusted basis and could actually begin to decline in 2008, and ... the strong portfolio capital inflows of a few quarters ago seem to be drying up as domestic equity and property markets fall.

On this question, I tend to support Dr. Jen.

Looking just at the reserves data is -- at Micheal Pettis notes -- potentially misleading: China’s state banks seem to have accumulated a lot of foreign exchange in the second half of 2007, lowering reported reserve growth. The banks were -- according to SAFE -- allowed to meet their reserve requirement by holding dollars. But supposedly the big state banks were called and encouraged to meet their reserve requirement by holding dollars.

The sum involved is quite large.

Logan Wright of Stone and McCarthy thinks that the big state banks could have been encouraged to stash away up to $100b in the second half of 2007. Stephen Green of Standard Chartered has noted that an obscure line in the PBoC’s balance sheet -- other foreign assets -- increased by over $75b in 2007, mostly at the end of the year. He thinks this corresponds to the rise in the banks fx holdings. That particular line had been stable up until recently.

Add those sums to China’s reserve growth and the picture changes.

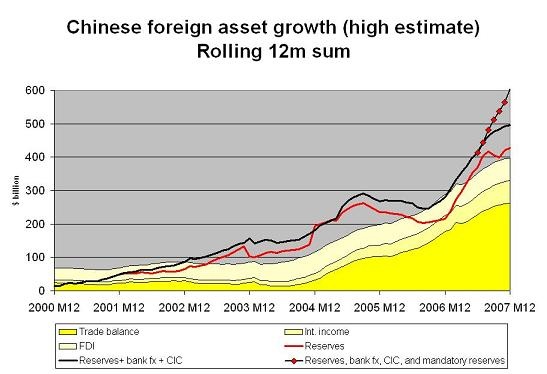

Hot money flows are usually defined as the gap between the sum of China’s trade surplus, the interest income on its reserves and known FDI inflows and China’s reserve growth.

However, if the banks are adding to their foreign exchange holdings at the request of the central bank, that holds down reserve growth. The foreign exchange the Ministry of Finance purchases from the PBoC to finance the CIC also holds down reserve growth.

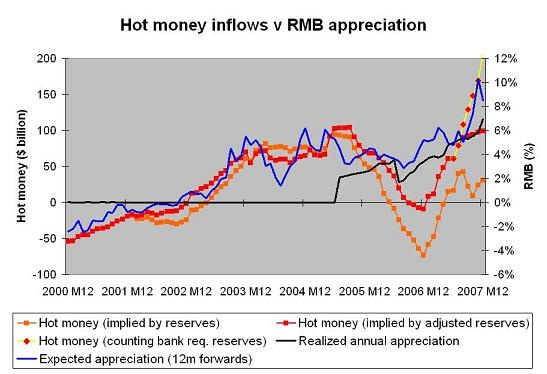

Much of the debate, consequently, hinges on the scale of these efforts. Consider the following two graphs -- which have been slightly updated from the graphs in my January paper on China’s reserve growth.

The first shows underlying trade,income and FDI flows v various measures of reserve growth. The size of hot money flows can be inferred from the size of the gap between the shaded area and the various lines showing reserve growth.

The second makes the hot money flows implied by the various measures of reserve growth in the first graph explicit. The orange line shows the hot money flows implied by China’s reported reserves, the red line shows the hot money flows implied by China’s reported reserves plus the rise in the banks "other fx liabilities" and "purchases and sales of foreign exchange" (balance sheet items that I think correspond with funds shifted from the PBoC to the banks, as explained my paper) and the yellow and red line shows hot money flows if the rise in the banks fx reserves estimated by Logan Wright is added to the adjusted reserves total.

To be clear, I do not know which is the right number. There is real risk that adding the assumed rise in bank fx holdings corresponding to the rise in required reserves to the "adjusted" total may end over-counting the increase in the Chinese state banks’ foreign exchange holdings.

Ubernerd points -- with apologies to uber-housing crisis blogger Tanta of Calculated Risk.

In a recent paper (sorry, no link available), Stephen Green of Standard Chartered highlighted an unusual roughly $80b ($78.6b, at year-end exchange rates) rise in the PBoC’s other foreign assets, a rise that came at the end of 2007. It isn’t totally clear to be why a rise in the banks fx holdings should lead to a rise in the PBoC’s foreign assets, but this is China, so you never quite know. The timing of the rise in this line item matches the timing of the reported change in China’s reserve policy that led the banks to meet their reserve requirement with fx.

Green links this to changes on the liabilities side of the state banks foreign currency balance sheet -- notably a $100b rise in "purchases and sales of foreign exchange" in the second half of 2007. The link would make sense if the banks are hedging the rise in their fx holdings with the central bank, as some press reports suggest.

However, the line item hasn’t been stable either: liabilities from the "purchase and sale of foreign exchange" fell by $45b in the first half of 2007, back when China’s reserve growth was surprisingly large. So the total increase in the banks fx liabilities from purchases and sales in 2007 is only around $55b.

Moreover, another line item in the banks foreign currency balance sheet -- "other fx liabilities" -- seems to move with purchases and sales. It rose by $54b in the fist half (offsetting most of the fall in outstanding liabilities from purchases and sales of fx) and then fell by $57b in the second half of 2007. In the past, I thought the two moved together because the liabilities from "purchases and sales" stem from swap contracts that hedge the banks underlying fx exposure from the recapitalization, but that is just a guess.

Basically, we know that in 2007, other foreign assets of the central bank rose by $75-80b (depending on the exchange rate conversion), banking system liabilities from "purchases and sales of foreign exchange" rose by about $55b (with a big fall in the first part of the year and a big rise in the second part of the year) and other foreign currency liabilities fell by a bit over $3b.

We don’t yet know how all these changes relate to each other. A lot of variables are moving, and China hasn’t really clarified how they all add up.

End ubernerd balance sheet points

Bottom line: it seems likely that the banks foreign exchange holdings stopped increasing in the first part of 2007, and then rose rapidly in the second half of 2007.

That in turn influenced reported reserve growth, and thus the implied pattern of hot money flows

On balance I think the evidence suggests that hot money inflows haven’t fallen off but rather that some of the rise in reserves has been shunted into the banks. It is true, as Dr. Anderson argues that the equity boom is no longer pulling in funds. However, a faster pace of RMB appreciation -- combined with falling rates in the US -- offers another good reason to move money into China.

It certainly seems to have made it hard to convince private Chinese investors to move money out of China. Even Hong Kong has lost its allure.

That matters. As Henny Sender noted in the FT, right now China’s government has an effective monopoly on capital outflows from China. And rising Chinese government investment in other economies makes many countries’ governments -- not just the US government -- nervous.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store