China’s Foreign Exchange Management: December 2024

This is this first blog in an ongoing series which will provide a monthly look at the various indicators of China’s foreign exchange management.

January 29, 2025 2:00 pm (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

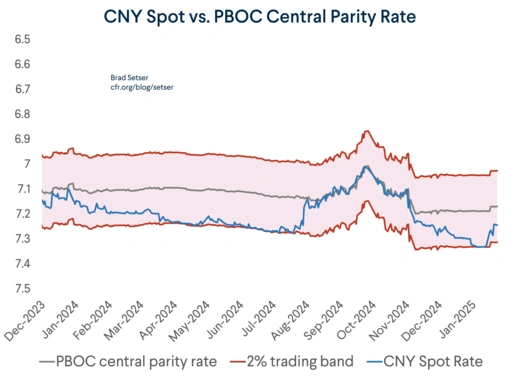

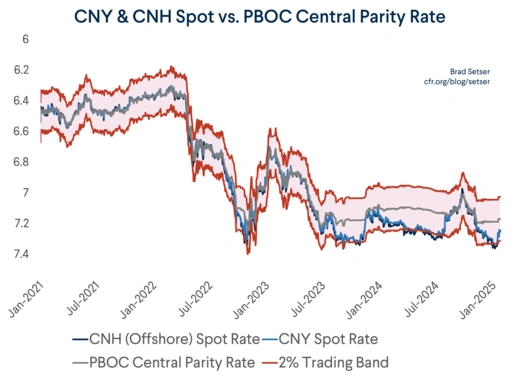

China’s renminbi appeared to be under pressure in most of December and the first part of January, reaching a 16-month low just before Trump’s inauguration. But the yuan rallied on news that Trump wasn’t immediately imposing tariffs on China—and was seeking an early summit with China’s President Xi.

The fix was (once again) fixed when the yuan was under the most depreciation pressure, with the weak edge of the yuan’s two percent trading band starting to bind. There was essentially no movement in the fix from mid-November to mid-January, a clear signal of the PBOC’s statement commitment to stability. But with the yuan’s surprise rally on the news that China wasn’t a day one tariff target, the PBOC has allowed a modest appreciation in the fix.

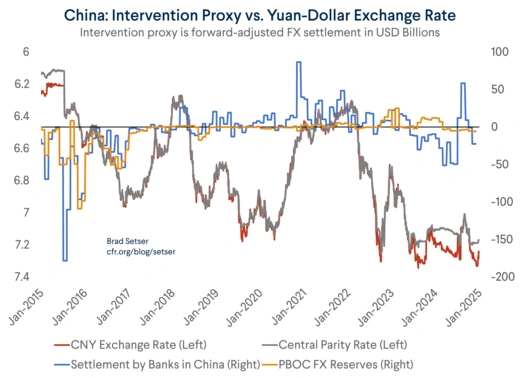

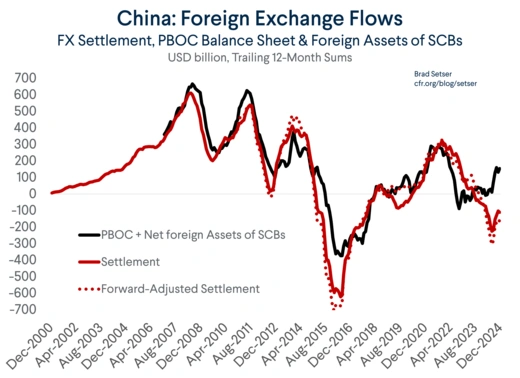

But it is still worth noting that the intervention proxies for December—net settlement by Chinese banks on behalf of clients, state commercial bank and PBOC FX holdings—date back to period when the fix was stable, and the yuan was trading weak relative to the fix. That makes the fact that they send conflicting signals about the mechanics of China’s current intervention activity especially puzzling.

Settlement

More on:

The settlement number historically has been the best indicator of China’s currency intervention, as it captures the activity of both the PBOC and the main state commercial banks. December’s data release indicated net sales, after adjusting for forwards, of $22 billion.

The net sales of foreign exchange align with expectations of a country that is trying to stabilize its currency in the face of depreciation pressure from expectations of trade tension and a rate cutting cycle.

PBoC FX Reserve Flows

The PBOC balance sheet data indicates also shows small FX sales in the month of December. At $5 billion or so, this number is modest and on its own suggests relatively limited depreciation pressure. However, in recent months the PBOC balance sheet change has not been aligned with market indicators of pressure, and thus it may not provide much of a signal.

The State Commercial Banks

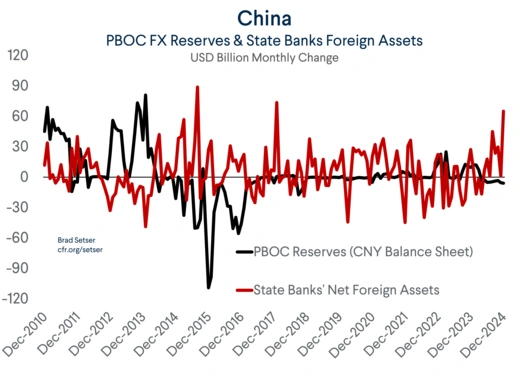

In recent years, the state banks appear to have had the primary responsibility for stabilizing the yuan.

As the chart above shows, the PBOC’s foreign exchange reserves have been mostly stable over the last eight years. The change in the state banks' net foreign asset position has in turn become a more reliable indicator of the scale of Chinese activity in the market.

More on:

This indicator did not behave as expected in December, as the state banks’ net foreign assets were substantially positive—with an increase of about $65 billion.

The PBOC balance sheet showed small net sales, as did the broader settlement data. Both data points are consistent with the yuan’s trading at the weak edge of the band and thus are now out of the ordinary in the current context. The large increase in foreign assets held at the state commercial banks, on the other hand, is strange.

To be clear, China’s central bank and its intermediaries (i.e., the state banks) would normally need to sell dollars to meet dollar demand and reduce depreciation. An increase in the combined foreign assets of the state banks and the PBOC, on its face, indicates the opposite course of action, namely net purchases of dollars.

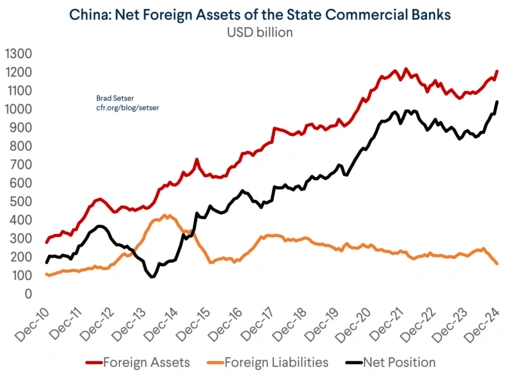

There are some possible explanations. The data shows that the banks paid off some foreign liabilities in December. Other data points show an increase in domestic foreign currency deposits, which would allow the banks to fund their external foreign assets domestically.

Other explanations include the widely reported activity of the state banks in the swaps market. The SCBs reportedly often swap yuan for dollars and then sell those dollars in the spot market. This combination would leave the reported on-balance sheet foreign asset position of the state banks unchanged, while increasing their off-balance sheet liabilities. If the state banks swapped for a lot of dollars in anticipation of future pressure but didn’t sell those dollars immediately, the reported foreign assets of the state banks would rise.

The swaps market activity is opaque and not fully understood by many outside observers. Box one of the November 2024 Treasury foreign exchange report provides a detailed overview.

Historically, the sum of the monthly changes in the PBOC balance sheet and the change in the net foreign asset position of the state banks have been roughly equal to net foreign exchange settlement.

That makes logical sense given that settlement includes the state banks. In 2024, though, these data series have diverged—with settlement showing net foreign exchange sales over the course of the year while the net foreign asset position of the state banks showing a close to $200 billion increase in their foreign asset position. This divergence poses a puzzle that we have yet to resolve.

The Trade Balance

The other potential explanation is that outflow pressure was reduced in December (despite the yuan’s apparent weakness) and thus China’s large trade surplus flowed in the net foreign asset position of the state banks.

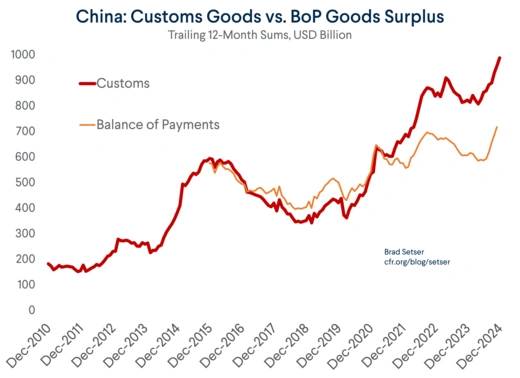

China’s export performance in 2024 was remarkably strong.

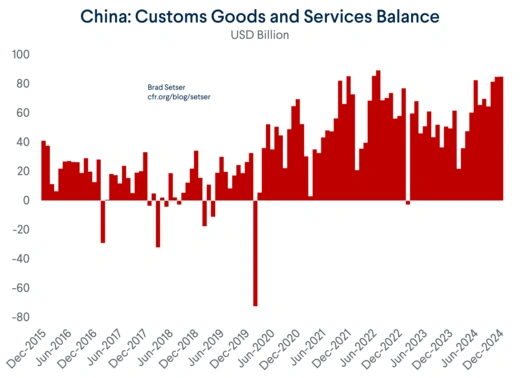

The December goods surplus (in the customs data) was nearly $105 billion ($90 billion in the balance of payments data). Add in a services deficit of $20 billion and the net influx of foreign exchange from foreign trade should have been around $85 billion.

However, expectations of further monetary easing in response to China’s domestic slump and expectations of further depreciation in response to expected tariffs would normally be expected to generate sizable outflows—making the apparent flow of the surplus into domestic foreign exchange deposits and a rise in the state banks net foreign asset position a real puzzle.

Conflicting Signals

The conflicting signals in the December data do align with the broader divergence of intervention proxies observed over that last two years or so, and there is no doubt that the PBOC is trying to manage competing imperatives.

On one hand, the PBOC has committed to act more like the Fed, relying more on “price-based” monetary transmission and shifting away from what China calls “quantitative objectives” (i.e. credit quotas, reserve requirements, direct or near-direct administrative control of deposit and mortgage rates).

On the other, the PBOC has repeatedly indicated that it remains committed to the stability of the yuan, and that commitment has been backed by the PBOC’s willingness to hold the yuan’s fix (the central point in the day’s trading) fixed for extended stretches to resist depreciation pressure.

A fix at around 7.2 effectively blocks the spot yuan from falling below 7.34—and there does seem to be more willingness (for now) to allow the fix to appreciate during periods of reduced stress than to allow depreciation during periods of increased stress.

The data points for January, which will be out in late February, promise to be equally interesting—and will warrant similar scrutiny.

Online Store

Online Store