- Experts

- Election 2024

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

FeaturedIntroduction Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election heightened concern over efforts by authoritarian governments to both redirect foreign policy and undermine confidence in de…

Council Special Report by Miles Kahler October 23, 2024 Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedThis symposium was created to address the broad spectrum of issues affecting Wall Street and international economics. It was established through the generous support of Council board member Stephen C. Freidheim and is copresented by the Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies and RealEcon: Reimagining American Economic Leadership.

Virtual Event with Emily J. Blanchard, Matthew P. Goodman, David R. Malpass, Elizabeth Rosenberg, Janet Yellen, Michael Froman and Rebecca Patterson October 17, 2024 Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies

- Related Sites

- More

Social Issues

Immigration and Migration

Record numbers of migrants seeking to cross the southern U.S. border are challenging the Joe Biden administration’s attempts to restore asylum protections. Here’s how the asylum process works.

Jun 4, 2024

Record numbers of migrants seeking to cross the southern U.S. border are challenging the Joe Biden administration’s attempts to restore asylum protections. Here’s how the asylum process works.

Jun 4, 2024

-

Why are People Fleeing the Northern Triangle?Tens of thousands of migrants from a region known as the Northern Triangle are arriving at the U.S. southern border. Here’s why they’re making the arduous journey.

-

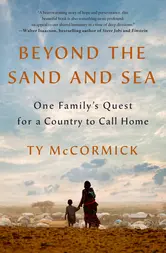

Beyond the Sand and Sea

![]() From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home.

From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home. -

Migration at the U.S.-Mexico BorderPaul Angelo, fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, discusses the migrant situation at the U.S.-Mexico border. This webinar is part of the Religion and Foreign Policy Program's Social Justice and Foreign Policy series, which explores the relationship between religion and social justice. Learn more about CFR's Religion and Foreign Policy Program. FASKIANOS: Welcome to the Council on Foreign Relations Social Justice and Foreign Policy webinar series. I'm Irina Faskianos, vice president for the National Program and Outreach at CFR. As a reminder, today's webinar is on the record, and the audio, video, and transcript will be made available on our website CFR.org, and on our iTunes podcast channel, Religion and Foreign Policy. As always, CFR takes no institutional positions on matters of policy. We're delighted to have Paul Angelo with us today to talk about migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. We have shared his bio with you, but I'll give you a few highlights. Paul Angelo is a fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he focuses on U.S.-Latin American relations, transnational crime, military and police reform, and immigration among other topics. He was formerly an international affairs fellow at CFR and in this capacity, he served in the State Department as a political officer at the U.S. Embassy in Honduras, where he managed the ambassador's security and justice portfolio. He provided technical assistance to the Honduran Police Reform Commission, supported strategy development agenda-setting for Afro-descendent, indigenous, and LGBTQ networks to improve civic engagement; and led policy and legal analysis on violence, crime and migration trends. He's a former active duty naval officer, and has completed several tours. And he has written commentary in many publications, including Foreign Affairs, our magazine, The New York Times, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, and the Miami Herald to name just a few. So Paul, thanks very much for being with us today. Obviously, we're seeing a lot of movement on the U.S.-Mexico border. Some have argued that it is mushrooming now that the Biden administration has come to government, so if you could talk about what's happening and maybe address the root causes, as to why migrants are making their way to the U.S. ANGELO: Great, thank you, Irina, and thanks to our support teams at CFR for setting this up. And for the invitation to join you all today. It's a pleasure to be on this call with you. And I think my real value add in this conversation is in the discussion of the root causes of migration, because of all the time that I've spent living and working in Central America, particularly in Honduras, but I also have experience in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua doing field work. But before I get into that discussion on the drivers of migration at the U.S. southern border, I'd like to clarify what's actually happening at the border today, because I think that there's a lot of misinformation in the news. Indeed, the news media has latched onto the term "crisis." But I think that betrays the reality of what we're observing. Yes, of course, there's a lot of desperation at the border. Yes, there are a lot of people, and we are likely going to see for the year 2021 a significant jump from pre-pandemic migration levels. But what we're seeing at the border state is not materially different from what we were seeing in the fall, or even just prior to COVID-19. The truth is that we've been managing a crisis on the southern border for decades now. And every single year from 1973 to 2009, there were more than 500,000 migrants apprehended, irregular migrants apprehended annually at the U.S. southern border. During the past decade, what we were actually seeing was historic lows in terms of the number of undocumented migrants seeking to gain access to the United States. There was only one year in the past decade, where the number of migrants apprehended at the U.S. border peaked over 500,000, and that was in 2019, when the Trump administration had purportedly sealed off the border and effectively closed off opportunities for asylum. In fact, 2019 was a banner year and I think a lot of what we're seeing for 2021 is going to be built up or pent up demographic pressure that accumulated over 2020 when the Trump administration was not actually enacting protocols to allow migrants and asylum seekers access to U.S. territory. I'd also like to take advantage of this moment to remind everyone that surges at the border are cyclical and seasonal. They respond to weather patterns, labor demands, and enforcement regimes, not just in the United States, but also elsewhere in Latin America, especially in Mexico. And so I would say that due to the Trump era programs, such as the migrant protection protocols, known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, and the process of metering, in January of 2020, just as President Joe Biden was on the eve of the inauguration, was set to take office in the White House, there were already some 42,000 asylum candidates who were camped out on the Mexican side of the border, who had not yet been processed for U.S. immigration hearings, or excuse me, asylum hearings in the United States. And so what we're seeing right now is a build up in demand, in addition to regular migration patterns. And these points of clarification are not to deny that irregular migration is a major challenge for the United States in the southern border. But I want to make sure that we're having an honest conversation about what's happening today. And in fact, it's unclear to me why what's happening at the borders is a surprise to so many people because worsening conditions in Mexico and Central America are a well-trodden narrative. And although we saw an overall dip in migration during 2020, due to COVID-19 pandemic, and the closure of borders in response to the pandemic, the pressure to migration, excuse me, the pressure to migrate in Central America and Mexico only accelerated. And so the only sustainable solution to help Central Americans and Mexicans address the root, contain migrant flows, is to help address the root causes. And to this end, the Biden administration is requesting four billion dollars in foreign assistance from Congress. And it started to make positive personnel decisions to shepherd this initiative. Why is it so necessary and what will it address? I'd like to zero in on four main issues. Firstly, the economy. Secondly, security. Thirdly, governance. And fourthly, climate change. On the economic front, I don't think we can talk about economic issues in Latin America in 2021, without having a discussion about COVID-19. In absolute terms, Latin America and the Caribbean has been the most affected region in the world by the pandemic. It is a region that comprises only 8 percent of the world's population, but 18 percent of the known COVID cases, and some 27 percent of the known COVID deaths. And that's not accounting for systematic underreporting by Mexico's, excuse me, by the region's second-most populous country, which is Mexico, it's estimated that there were over 300,000 excess deaths in 2020, which were likely attributable to COVID-19. We've also seen that the region was impacted due to the interruptions in supply chains, and the imposition of very strict lockdowns. And because of these factors, regional economic contraction in Latin America for 2020 was at around 7.7 percent. I would also note that Guatemala and Mexico, which are two of the countries of most concern to us today, were both above that regional average. In 2020, 34 million Latin Americans lost their jobs. We saw a dip in remittances from the United States. Given the economic recession here in the United States, that dip has now recovered. But nonetheless, it exposed the fragility of finance networks for many living in Central America and southern Mexico. I remind everyone that a majority of people in Guatemala and Honduras already live below the poverty line. And across the Northern Triangle, more than 70 percent of the workforce is employed in the informal economy, which means that these people do not have access to insurance or protections, and their access to medical attention is scarce. The tragedy, the travesty, that the region has faced on the economic front has only been exacerbated by a long-standing pandemic, excuse me, a long-standing epidemic of insecurity. Although in 2020, we saw reductions in homicide across the Northern Triangle, the Northern Triangle countries still rank among the most dangerous countries in the world. And in 2019, Mexico had set a record for the highest number of homicides in the country's recent history. It almost equaled that number in 2020, despite the fact that it was imposing strict measures to contain the pandemic in some parts of the country, especially in parts of the country that had previously been reporting very high rates of violence. There are a lot of factors that we can go into in the question and answer period if you'd like to discuss why we've seen a dip in homicides, but I don't suspect that that dip is sustainable going forward. And I think that we will see insecurity, high rates of insecurity resume for 2021 and 2022. The third factor that I'd like to point to is an overall failure in governance. In addition to state capture by criminal groups, Central America is rife with political corruption. And we've already seen the inflation of government contracts to distribute humanitarian relief and COVID-19 vaccines in places like Honduras. This will remind close watchers of Honduras, or close watchers of Central America in general, of the Astrapharma scandal back in 2015, in which the Honduran government provided preferential access or preferential contracts to a pharmaceutical company that was owned by the National party's congressional leader, who happened to be in the business of making placebos or inert medicines that were being administered in public hospitals that resulted in the deaths of dozens of people. Likewise, there was the Pandora scandal in Honduras that emerged in the following years in which the government was diverting public funds to shell NGOs as a way of paying off bribes to members of Congress, or members of the judiciary. And, likewise in neighboring Guatemala, everyone will remember the Alenia scandal which saw the ouster of former president Otto Pérez Molina in 2015. There was some progress that was being made on going after perpetrators of major political corruption in Central America with the internationally-backed CICIG, and the internationally-backed, OAS-backed MACCIH in Honduras, which were beginning to show results. But as these internationally supported investigative bodies, that were seeking to combat impunity and corruption in Honduras, and Guatemala, were making impressive results. And as their investigations get closer to the inner ring of presidents at the time of their mandates, were cut short. And so we've seen an overall reversal in terms of the anti-corruption crusade that was gaining steam and starting to bear impressive results in Central America, in the 2016-2017 period. And then finally, when we talk about root causes, we can't have this conversation and particularly not at this moment without talking about climate issues. Everything that I've just mentioned, there's mounting demographic pressure for people to migrate. But I think the most proximate cause for migration in this current wave that we're seeing, are the two back-to-back category five hurricanes that hit Central America in the fall. They destroyed 90 percent of Honduras's bean and corn crops, which was a death sentence for many in a region where food insecurity was already pervasive. For those of you familiar with the region, you'll know that there's a stretch of territory called the Dry Corridor that starts in Costa Rica and extends all the way up to southern Mexico. And in that tract of territory, in 2019, there were already 1.4 million people in Central America who were food insecure. These hurricanes also didn't just destroy crops, they displaced people in communities, many of which had settled or built their livelihoods alongside river beds, killed some 140,000 livestock, and completely devastated plantain and banana farms, and other large large-scale agriculture. So further reducing employment opportunities for the agricultural workers in Central America. I would also note that this is coming on the heels of a decade of disruption of traditional livelihoods due to climate change. The region was already seeing 40 percent less rain than historical annual averages, and rising temperatures and regular rainfall led to anything from coffee rust, to a bark-eating beetle that was disrupting timber crops, to the black sigatoka, which is a fungus that has been ravaging banana crops in Honduras in recent years. And so the travesty that we saw in the fall with the hurricanes, the two back-to-back hurricanes, has only compounded the issues, the pressures to migrate that many subsistence farmers were already facing. So that sort of addresses the root causes conversation, I don't want to deny that there are also pull factors here in the United States, most notably our own economic prosperity as a country. But I'm happy to go into those with the time we have remaining, but at this point, I'll cede the conversation back over to Irina, and look forward to having a good question and answer period with all of you. FASKIANOS: Paul, that was fantastic. Thank you very much for dispelling the misinformation and addressing the root causes. So we want to go to all of you if you want to ask a question, please raise your hand by clicking on the icon. And you can also type your question in the Q&A box, but we'd love to hear from you live. So please do raise your hand. And there are just thank-you notes in the chat, saying this is very informative, and will will it be available after the fact? And yes, it will be available after the fact, we'll have a transcript and a link to the webinar, so you can capture all the facts that Paul has mentioned. And in this short time, it's really been enriching. So, while we wait for questions, let me see hold on a minute. We do have questions. Three hands. Okay, so I'm going to go first to Todd Scribner. And please identify yourself, your affiliation. And please unmute yourself. SCRIBNER: Hi, my name is Todd Scribner. I'm here from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Migration and Refugee services, their policy office. I'm curious, we're really big on the issue of root causes and addressing root causes is really the long-term solution to any of these problems. I'm wondering if you can point to any models from the past in which countries have worked with other countries to address root causes of this sort, that might be driving migration, that can be seen as a successful example of working with another country to kind of fix problems that are that are underlying drivers in the first place. Do you know of any? ANGELO: Yeah, thank you, Todd. And in terms of this hemisphere, it's very hard for me to point to any positive, enduring examples of that. But I would sort of divert everyone's attention back to what the Obama administration was attempting to do in its final years. You will all likely recall that in 2014, there was an uptick in child migration, or unaccompanied child migration to the United States. In the span of nine months, we saw over 60,000 unaccompanied minors, most of whom were from Central America presenting themselves and seeking asylum at the U.S. southern border. And the Obama administration recognized that the only way that we were going to be able to turn the tide on that wave of migration was to help address the root causes the things that were propelling these young people from Central America and southern Mexico to the border. And the narrative that took hold here in Washington was one that was focused on violence and insecurity. Of course, these had long been some of the most violent countries in the world. In 2014 and 2015, I believe, San Salvador and San Pedro Sula were the murder capitals of the world. Honduras and El Salvador for a couple of years were competing back and forth for having the highest national homicide rates. And so the idea was that many of these young people were vulnerable to gang recruitment. And the U.S. government sought to help reform security sectors and judicial sectors to combat impunity, which over the span of the operation of the CICIG, we saw the homicide rate in Guatemala, for instance, dropped by more than half. But also, just as important, there was a real focus on providing community policing, and improving relations between the state and the most vulnerable communities in the countries of the Northern Triangle. This is something that I worked on in 2015-2016 in Honduras, it was an initiative known as the “place-based” strategy. And what it really focused on was firstly instituting community police units. And these were police that were specifically trained not to have a repressive presence of the state, but police units that were there to help with things like getting the cat out of the tree, or providing directions to somebody passing through a community. Also, these units of a community, police engaged in things like medical brigades, or providing educational materials to schools in their areas of operation. And with this model, and with a significant investment from both the Honduran government and the U.S. government in building things like infrastructure in the most vulnerable communities, in the span of two and a half years, we saw significant reductions in homicides. And in the two communities where I worked [inaudible] we saw homicide reductions by over 60 percent in both of those communities in just over two years. That was a model that was working. Unfortunately, the Trump administration came into office and in 2019, throws all U.S. assistance to the countries of the Northern Triangle on the pretext that the governments of these countries weren't doing enough to help stem migration. And I have to believe that that decision to freeze aid, and then the decision not to turn all that aid back on for the remainder of the Trump administration, really disrupted the momentum needed for the place-based strategy to take hold. The idea is that in a place-based strategy, these communities where we saw significant success, they were meant to be a geographic nucleus. And so the idea was that the community policing model would extend to neighboring communities until it had encompassed the most vulnerable areas of places like Guatemala City, San Salvador, [inaudible] San Pedro Sula, and that just hasn't happened. And so I think that going back to that model, and reinvigorating the place-based strategy is one example of how the Biden administration can once again start chipping away at the drivers that have been propelling people, and particularly young people, to the U.S.-Mexico border. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Let's go next to Tereska Lynam. LYNAM: Hi, thank you for taking my call. Can you hear me okay? FASKIANOS: We can. LYNAM: Oh, and thank you. So, wonderful presentation, thank you so very much. I'm from Oxford University and my experience, but I live in the U.S., my experience is that, at least in my circle of people, we're really interested in the human rights abuses that have occurred, particularly through the Trump administration with the separated families. That's what the media focuses on, obviously. Because you're talking about policy and policy, unfortunately, is boring to most people. So they don't really look at the underlying causes. They look at what's being blared at them that day. So I would love it if you could talk about how these human rights abuses are being managed right now, how people are being processed, and the border issues that we're continuing to hear. And then what kind of media advice, if you could, give to Vice President Harris, who's been charged with taking this over, in terms of doing the razzle dazzle that will make people happy, give them the sound bites they want, while also addressing these very complicated policy issues? Thank you. ANGELO: Great. I think the answer to your second question second question helps inform the response I have to the first question. So I'll tackle that first. I think the most important thing that Vice President Harris and Ricardo Zúñiga, who's the new presidential envoy for the Northern Triangle of Central America, can do is try to relocate the drama that is unfolding at the border, and the attention that's unfolding at the border to other countries. And it's not to say that we should close off our asylum system. But what we need to do is introduce or reintroduced programs that gave people the opportunity to seek asylum or to claim refugee status abroad. There was a pilot program that was started in the Obama administration that would allow migrants, or refugees, excuse me, from the Northern Triangle countries to seek asylum via the United States in a place like Costa Rica, which is considerably safer, has higher sort of indicators for all measures of socioeconomic development. Likewise, there was an initiative that the Obama administration instituted and has now been turned back on by the Biden administration, called the Central American Minors Program, which allows for in-country refugee processing. And so to the extent that we can exert a degree of control over by preventing people from taking a dangerous journey northward, one in which every step of the way, their human rights are likely being violated. Keeping them in the region and giving them opportunities to seek relief in the region, is probably the best bet for giving our Vice President the sound bites that she would need to satisfy a rather demanding and perhaps even unrealistic public here in the United States. But in terms of what's happening at the border, vis-a-vis human rights abuses, and/or the denial of asylum that was happening quite systematically during the Trump administration, the Biden administration has sought to bring back online our asylum system, reinstate processes to manage cross border flow responsibly, and to surge assistance to address the root causes. Those are the three main pillars. We've seen already thousands of individuals who are being held under the migrant protection protocols, indefinitely, brought across the border and assigned dates for their initial asylum hearings. And I'll just remind everyone that during the Trump administration, there were over 42,000 cases of individuals who were being held in Mexico under MPP, that faced consideration by U.S. immigration courts, but only 638 of those people were granted relief. And so it was a very, very high bar for asylum seekers to actually be granted asylum under the Migrant Protection Protocol Program. It's too early to tell what kind of results or what kind of yield the Biden administration will produce given that it's so early, but nonetheless, that the MPP participants are going to be the initial priority for the Biden administration when it comes to delivering on the issue of asylum. Likewise, unaccompanied minors are no longer being turned away, and instead, are being brought and transferred to Office of Refugee Resettlement facilities until they can be relocated to sponsors who are already in this country. The Biden administration, like I mentioned, had already turned back on the Central American Minors Program, so that refugee children can request protection in their countries of origin and then be safely flown to the United States if they qualify rather than having to pay into the pockets of human traffickers and human smugglers across the Central American isthmus and into Mexico. We've seen that other agencies in the U.S. government have now sought to bring on temporary shelters, like FEMA is building temporary shelters to deal with this ballooning of migrants that we're seeing at the border. And most of the incapacity that we have at the moment has to do with the fact that we're also confronting a pandemic and have to implement appropriate public health measures. And so in order to make sure that people are sufficiently distanced, and that we're engaged in the best, most up-to-date and best public health measures to deal with this pandemic, that's really driving the need for the construction of additional shelters. But broadly speaking, I think that the situation is certainly better. We're seeing refugee families as well, or asylum seeking families, being brought into the United States, not all of them are being turned away, as they were under the Trump administration under the pretext of Title 42, which allows the U.S. government to turn back people who are seeking to gain access to the U.S. national territory on the pretext of public health measures. So I think we're slowly and methodically seeing the Biden administration turn back on many of the processes that were stunted during the Trump administration, and particularly with the advent of the pandemic. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Just to build on that question, from Michael Thomas of Dartmouth College. Do you think that the appointment of Vice President Harris to oversee this is a good move, essentially? And I'm assuming the answer to this is yes, but is there a number that you're hearing about the number of Central American refugees who can be resettled this year? ANGELO: So great question. One of the things that the Biden administration has in terms of outstanding work, is that it has yet to raise the refugee cap or the asylum cap that was introduced under the Trump administration. Some of you will remember that during the Obama administration, there was a cap on 110,000 refugees who are granted relief here in the United States annually. And that was reduced from the Trump administration to a mere 15,000. And so I fully expect in the weeks to come that the Biden administration will resume or reinstate the cap that was operating under the Obama administration, and may even expand it a bit to offer more generous relief, given the upswell in demand that had been building because of the restrictions that were imposed by the Trump administration. But in terms of the appointment of Vice President Harris to deal with this issue, I think really, I think symbolically, it's a very clever move. Vice President Harris herself is the daughter of two immigrants, one of whom is from the Caribbean region. And so I think that the empathy that she would bring to that role is symbolically important for the administration. I think it makes sense from a political standpoint, it just shows that this administration is taking very seriously the issues from the border, and not just build a wall and seal off the border to prevent migration, but rather, really wanting to engage with the countries of the region and providing and implementing sustainable solutions. And so I think that it's a win across the board. And like I said, I think the team that the Biden administration has brought online to deal with border and Central American issues, Ricardo Zúñiga and Roberta Jacobson, Ambassador Jacobson, who was our ambassador to Mexico under the Obama administration into the early first year of the Trump administration, he couldn't find a better group of people to shepherd this reengagement with Central America and Mexico on the issue of migration. FASKIANOS: Great. Let's go next to Alan Bentz-Letts, who has his hand raised? And please unmute yourself. BENTZ-LETTS: Oh, hi. Thank you for your talk so far and for the chance to ask a question. I'm a retired chaplain, and a member of environmental and peace and justice groups at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. In 2009, both President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton supported what was really a coup against the existing president who was working to help the poorest people in Honduras. And since then, there's been just president who has been corrupt and decimated human rights in that country. And so there's a lot of evidence for saying that it's the existence of corrupt and very right-wing governments in Central America that link to gangs and that are causing the really terrible situation for poor people and for the common people in those countries. How would you respond to the claim that unless the United States changes its foreign policy, that this situation of migrants coming to the U.S. is going to continue and continue to be a serious problem? ANGELO: Yeah, I appreciate that question. And I think that the, particularly the Trump administration's decision to really cozy up to President Juan Orlando Hernandez in Honduras was problematic for so many reasons. In fact, in 2017, you'll likely remember that there was an election that took place in which the opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla was set to win the election, was leading in the polls. And then in an act of God, the counting machines lost their electrical feed, and when they were turned back on some twelve hours later, President Juan Orlando Hernandez, the incumbent, was winning. And then he actually ended up winning the election, at least in the formal count that was made, despite the fact that there were significant international protests to that election, to include from the Organization of American States, which was suggesting that Honduras redo the election, and invite international observation mission to oversee it. The Trump administration just outright recognized the incumbent government, which was a huge setback for democracy, was a huge setback for the opposition, and really took the wind out of the sails of people who felt that that finally Honduras was turning the curve. And that finally there was going to be some accountability for the corruption that had been, for many years, perpetrated by the National Party, which has been in power for most of the past decade. And so I do think that single foreign policy decision, the recognition of Juan Orlando's victory in 2017, was a major setback. And now that we're seeing in any number of drug trafficking cases that are being processed in U.S. courts to include a case of President Hernandez's own brother, who was found guilty of cocaine trafficking and money laundering in a New York District Court. We're seeing just how deep the tentacles of these organized crime groups run inside the Honduran government. And just this past week, an associate of Los Cachiros implicated Juan Orlando Hernandez again, in drug crimes, but also implicated former President Manuel Zelaya in the same kinds of drug corruption. And so what it really points to is, in a very nonpartisan way, pervasive corruption across the political class in Honduras. And the only way to tackle that, is really for the international community, led by the United States, to go after politicians and public officials who are engaged in public corruption. And to do so is something that has been at least floated by the Biden administration as a possibility through the establishment of a regional anti-corruption body that would be supported by perhaps the UN, or the Organization of American States, to really help nascent and sometimes inexperienced investigative and judicial officials in Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, conduct the kinds of investigations that are needed in order to bring public officials to justice. FASKIANOS: Thank you. I'm going to go next to Mark Hetfield, who runs HIAS, and has done so much work in helping refugees. So Mark, if you can unmute yourself. HETFIELD: Thanks, Irina. And thanks, Paul. I wanted to follow up on what Paul had said about the refugee ceiling and the presidential determination in the context of the Central American issues. You said that you believe that President Biden will raise the ceiling and I think all of us think he will, but the question I have for you, if you have any ideas, or insights, or theories, as to why hasn't he done it yet? Because on February 12, he sent Secretary Mayorkas and Secretary Blinken to Congress to present their fifteen page document explaining the urgent need for an emergency presidential determination on refugee resettlement. Again, February 12. And we're still waiting for it. The Biden administration has just continued to carry out the Trump administration's refugee resettlement policies 100 percent. Refugees were literally booked on flights and then had to be unbooked by the State Department, 715 of them, because of Biden's failure to sign the presence of determination that he promised on February 12. So, what's the holdup? And what's the tie in, if any, to the to the issues at the border? ANGELO: Yeah, I would just offer that I think likely part of it has to do with optics. I mean, now that the media has latched on to this so-called crisis at the border, any sort of major move that would signal a major increase in people who are being resettled in the United States, might not be politically palatable at the moment. But I would also say that we don't really fully have our immigration, and asylum, and refugee systems fully running and back online yet, this is a process. A lot of what the Trump administration did was tweak within bureaucracies. And so even though there are executive orders that signal in the direction of a more humane migration policy, more humane asylum policy, a lot of the procedures that have been enacted are bureaucratic procedures that have to be undone by the individual agencies or by the departments that are implementing them. And so I think there's probably an instinct to wait on raising the refugee cap until we have more sustainable, and workable, and regularized mechanisms in place that are happening at the level of the bureaucracy. FASKIANOS: Paul, I'm going to take a written question from Mary Yelenick, who is with Pax Christi International. She writes: “Can we fairly address the crisis in Latin America without a discussion of the U.S. historic military and economic interventions in the region?” ANGELO: Right, I mean, the United States, it's no secret that it had been specially trained, the Cold War played a less than positive role in the countries of the Northern Triangle, and the militarization of the region during that period is largely why we're seeing such high levels of violence across society today. A lot of the excess arms that were left over in the wake of civil conflict in Central America have been made available to the [inaudible] the street gangs, and drug trafficking organizations that in many spaces of Central America, rule the day and can exert significant armed influence over communities. And so I think that more than anything, is the reason why the United States needs to have a prominent seat at the table. The United States has a responsibility, I think, more responsibility to help alleviate a lot of the strife that was left in the wake of the conflicts that defined Central America in the 1970s and 1980s. Likewise, I would just say on the issue of firearms and the United States, I think in terms of building the kinds of confidence with the Mexican government right now, on the issue of migration, and in seeking a more positive working relationship with the administration of President Lopez Obrador in Mexico, the United States has to get a handle on its own obsession with firearms. A couple of years ago, I was speaking to a police officer in [inaudible], who gave me a figure that on average, there are 2,000 firearms that are either legally or illegally purchased in the United States that cross over the border to Mexico illegally on any given day. And that was in probably I think, that was a conversation I had in 2018. I'm not sure what the most updated figures are right now. But nonetheless, the scourge of violence that we're seeing beset Mexico right now, which, Mexico had historically had high elevated levels of violence, but in terms of high homicide rates, it wasn't typically among the top ten to twenty countries in the world, the homicide rate. Now we're seeing Mexico is exceeding Guatemala and El Salvador in terms of its own homicide rate, and for a heavily populated country, like Mexico, that's tens of thousands of people in any given year. And inevitably, when you trace the origins of the firearms that are being used in these homicides, a vast majority of them were purchased in the United States and illegally exported to Mexico. And so in terms, it's something that the Mexican government has long laid as an agenda item for bilateral relations with the United States. But until the United States is enforcing better its own border, and attempting to more systematically prevent the export of firearms from the United States to Mexico, I really don't think that we're going to see any sustainable gains in bringing violence down in Central America and Mexico. FASKIANOS: And, of course, we have our own debate now on gun policy in the wake of the tragic shootings in Colorado, and last week in Atlanta. So we have a lot of work to do here. Let's go next to Steven Gutow. And unmute yourself, Steve. Okay. GUTOW: I did it. FASKIANOS: You did it. GUTOW: You know, it's not easy for me, Irina, but I did do that. So. FASKIANOS: You did do it! Good. GUTOW: It's good to see you, Irina. And, Paul, thank you, thank you, for your service to our country, and also for your presentation to all of us. I live in the world of both policy and politics, and I never let politics get too far away from me, because I know that's a sure way to not be successful in winning anything. We live in a country that's very divided in terms of, I'm already seeing that the numbers going up and the concerns going up that Biden didn't do X and didn't do Y. And I'm more interested in what he hasn't done and what he has done. I'm more interested in hearing things he could do better than have and have been sort of shaded over by how great he is and how bad Trump is, because we all, I don't know if we all, I think that. But with that said, what is wrong? I mean, somebody woke up at 6:00 a.m. yesterday and said, "We can bring all the immigrants we want can't we?" I said, "Yeah, but we can't we can't win the 2022 elections if we do." My questions is, what is Biden doing wrong? And what did he do wrong, did he make some suggestions that everybody, we should basically should start coming over before he decided to say that they should wait? It's one of the things that the Democrats can do better and do better with not in terms of doing the more just things. I'm a rabbi, according to God, but doing the more just things according to the politics of America. ANGELO: Well, you know, I actually think that the administration has taken some very early and positive steps in signaling to migrants in Central America and Mexico not to come. In fact, you know, within a week of being named as the president's advisor on migration issues, Roberta Jacobson, Ambassador Jacobson, was on the airwaves, using the podium of the press secretary at the White House saying in Spanish, "Do not come. Do not come now. Now is not the time. We don't have any, our processes fully in place yet." And she did so in Spanish. And it was something that was replicated and aired on radio and TV throughout Central America. That's the kind of signaling that I think is so incredibly important, mostly because we're living in an environment right now in which misinformation creates reality. And so people in Central America, in the absence of that kind of signaling, in the absence of that kind of messaging, are going to latch onto whatever the human smugglers or traffickers are pushing out to them on social media or on radio spots, or even on WhatsApp chats. And so to the extent that the United States can help control that narrative, I think we're all the better for it. Likewise, as I mentioned, the restarting the Central America Minors Program is just, it's firstly, symbolically important, but secondly, it's practically important. The less that we can, or the more that we can prevent young people from Central America and their parents from putting them in harm's way by paying human traffickers to smuggle them across borders, and into the United States, or at least to the U.S.-Mexico border, the better off we can be, and the better off we can protect their rights. And so I think from that program, as well, we can contemplate other in-country refugee processing, that can help us in a more sustainable and more humane way manage the desire and flow to access the United States. FASKIANOS: Paul, to pick up on that point, from David Greenhaw, formerly of the Eden Theological Seminary, can you talk about the internal struggle on process in a family when they're so desperate as to send their children across the border unaccompanied? Because we know so many children are coming accompanied? ANGELO: Well, I think this is actually part of the incentive structure that we have given our policy in the United States. That because the Biden administration is now allowing minors, unaccompanied minors, to come across the border, and it's processing them and within a couple of weeks will likely, for many of them, find sponsors, family members who already live in United States with whom they can stay. I think that's actually encouraging people to send their children across the border and accompanied. Even if these entire family units are on the Mexican side of the border together. Many of them, and I don't have any firm statistics on this, but many of them may be presenting their children as unaccompanied minors, or their children may be presenting themselves as unaccompanied minors, knowing that it's a decision between, well, if my whole family can't make it together, at least, my son or daughter can have a better future. And they have a grandmother, or an aunt, or an uncle, or a cousin who's already in the United States. And so it's the sort of discretionary policy, which doesn't treat all migrants as equals, and not saying we should from a humanitarian standpoint, that is perhaps fueling the surge in unaccompanied minors that we're seeing at the border right now. Which is why the activation of the Central American Minors program is so incredibly important in preventing future waves of irregular migration of young children to the U.S.-Mexico border. FASKIANOS: Great, I'm going to go next to Alejandro, I'm sorry, I'm just pulling up the list. Yes. Alejandro Beutel, who has his hand raised. BEUTEL: Hi, can you hear me? FASKIANOS: Yes, we can. BEUTEL: Okay. Dr. Angelo, thank you very much for an illuming presentation. And Ms. Faskianos, thank you for facilitating this conversation today. This is an issue that is near and dear to me for both professional and personal reasons. The latter being myself as someone of Central American descent with family in Honduras and El Salvador, professionally, though, as well, even taking a more domestic lens on this. At New Lines, several colleagues and I are looking at the issue of far-right extremism here in the United States and in Europe. And one of the components to that is looking at nativism in a transatlantic setting. And obviously, that includes here in the United States. One of the things that we are doing as part of that is sort of a threat assessment of the impact that nativism can have on particular communities, including ones that have been historically disenfranchised, or marginalized, or targeted. And so in the context of the present discussion today, one of the things that is sort of on our radar, and I would love to sort of get your thoughts on this, is at the moment, it appears as though far-right extremist actors within the United States have their attentions diverted elsewhere. Certain rhetorical targets, like Antifa, Black Lives Matter, even the general opposition to the Biden administration, perhaps. But that said, is that in prior years, they have also, had a very strong emphasis on nativism, which operationally, we could define as Muslims and immigrants in general. And so my question then, in the context of this, given the fact that there is this sort of crisis narrative, if you will, that's butting up against an empirical reality that you've described at the beginning of your excellent presentation. My question would be, then, in terms of trying to diminish the prospect of sort of the social aperture, the permission structures for nativist violence and harassment, what could be done in terms of policy and political tone to diminish that, in your opinion? ANGELO: Yeah, I mean it's, I think the initial signaling from the Biden administration is an important one. The Biden campaign and the administration have long said that we are a nation of immigrants, but we're also a nation of laws. And so in order to make sure that we are living up to our, or fulfilling our promises as a nation, we need to continue to be a welcoming place for migrants. And at the same time, we also need to have the right procedures and processes in place in order to handle both the demands here in the United States for labor, particularly agricultural labor, which is a contributor of migration from Central America and Mexico. But likewise, the demand for opportunity, and even refuge here in the United States. And so, I think that's rhetorically, I think, signaling in that direction as a way to push back against the sort of nativist instincts. But I would also just cite that the Biden administration has presented to Congress a comprehensive immigration bill, which would provide a pathway to citizenship for the approximately 11 million undocumented migrants or immigrants who are already in the United States. And depending on the poll you look at, a majority of Americans support this measure. I've seen recent polling anywhere between 57 and 69 percent. But there doesn't really appear to be the kind of support for, in either chamber of Congress, for that kind of comprehensive immigration reform. And so I think that in terms of showing progress on immigration, and showing progress on a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants in this country, I think getting bipartisanship, piecemeal legislation focused on issues relating to migration, will help address some of that nativist instinct. If you can show that Republicans and Democrats in Congress can both agree on things like providing relief for DREAMers or for agricultural workers, which are currently under consideration in Congress at the moment, I think that's the most sustainable or feasible way of getting essential relief as quickly as possible to people who need it, and for an immigration system that needs it, and to do so in such a way that doesn't inflame the sort of the nativist segments of the U.S. electorate. FASKIANOS: Thank you. I'm going go next to Gonzalo Alers's question in the chat. He's at Drew University. And can you talk a little bit about the conditions of the detention centers, the relationship between the agents of governments represented, treatment of these peoples, and the presence of world observers, in terms of human rights organizations, and then just expand on that? And bringing in Hannah Stewart-Gambino's question, and religious actors on the border? Is the religion community helping affect change, or is that decreasing? Or what do you see? ANGELO: Right, so I think religious and civil society organizations are so incredibly important. Firstly, in monitoring and making sure that the United States actually is fulfilling its promise as a nation, and is living up to its values as a nation, in the administration of our migration and refugee systems. But that being said, at the moment, because of the restrictions on movement or on access, given the public health concerns in the midst of a pandemic, I think that there's certainly some understandable hesitancy to provide access to civil society organizations that have long been guarantors of transparency in the system. But nonetheless, I mean, I myself have not been to any of the detention facilities, and certainly not the makeshift ones that have come up in recent months, that have been brought online to deal with the surge. But nonetheless, my sense is that the administration is trying to do right by the individuals who are being detained and being held. And likewise in terms of the unaccompanied minors, there's a real commitment to trying to get unaccompanied minors who have come into United States, outside of these detention facilities, and inside the homes of sponsors who already live here in the United States. And so I would just say more broadly speaking, I think that civil society also has an incredibly important role to play in the administration of assistance, U.S. foreign assistance in Central America, as a way of addressing the root causes of migration. The Biden administration has already said that we are not going to engage with or provide assistance to institutions or individuals in Central America, who don't have our best interests or the best interests of democracy at heart. And that means that the aid is going to be largely conditioned on anti-corruption progress. And that aid that is not made available to governments, which will likely not be the majority of the aid, we made available to civil society, and especially religious organizations who are doing some of the most impressive humanitarian work coming around in Central America. And so I think that those kinds of partnerships and the ability of the United States government organizations, and departments like the Department of State, USAID, Department of Homeland Security, to outsource a lot of the good work that it's doing, that it intends to do in addressing the root causes of migration, to local civil society organizations and religious organizations is an incredibly important piece and should not be discounted in this broader discussion of how we're going to address the root causes. FASKIANOS: Fantastic. And I just want to raise Sister Donna Markham, who is with the Catholic Relief Services, put something in the chat she has noise in the background, so she can't say it herself. But just to bring to this discussion. For meeting with our agencies serving along the border, many of those seeking asylum are targets of the drug cartels, this fear of death or torture of their children is a major reason parents are sending the kids by themselves. And then she said, are there any successful strategies from the Obama administration for curbing the public of the cartels? ANGELO: I mean, I think this just goes to a broader conversation that is being had right now. In fact, earlier this week, Ambassador Jacobson, Ricardo Zúñiga, and Juan Gonzalez, who's the senior advisor, senior director for Western Hemisphere Affairs on the National Security Council, all met with the Mexican government on cooperating for a more sustainable and humane migration system, and greater cooperation, collaboration between the United States government and the Mexican government. And so, Mexico itself is dealing with a plethora of issues at the moment. As I said, it's one of the worst, in statistical terms, one of the worst affected countries in the world, when it comes to the pandemic. It hasn't secured the sufficient number of vaccines for its population, the vaccines it already has on the ground are not being distributed well enough. The U.S. government, in a good faith gesture, just made available 2.5 million vaccines to the government as well. But really, when it comes to migration and making, cutting down on the vulnerability of migrant populations to organized crime, and organized crime groups and gangs, particularly in Mexico, because of the migrant protection protocols, I would say that cooperation with Mexico is key. And in order to engender the kind of confidence that will reactivate U.S.-Mexico security cooperation, more broadly speaking, because much of that security cooperation, which had become a staple of the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship under the Bush administration, under the Obama administration, had lapsed during the Trump years. I would say that the U.S. government, as I mentioned earlier, really needs to get a handle on its own firearms issues, and greater enforcement of our own border and making sure that what's going across the border from the United States to Mexico, is regulated, just as much as we regulate what's coming across from Mexico to the United States. FASKIANOS: Great. And my apologies, Sister Markham is with Catholic Charities USA. So toggling between too many screens here. We are at the end of our time, and I apologize. I just wanted to see if you could close out, Paul, with a question from Tom Walsh, just about how we are engaging with the UN agencies such as the UN Office of Drugs and Crime, or International Organization on Migration? Or if this crisis is mostly a domestic and a regional multilateral issue? ANGELO: That's a fantastic question. And I think that there's a bigger role for the United Nations in particular to play in helping set up in-country refugee processing in the countries of Central America. Not all of the people who are seeking refuge in another country from the Northern Triangle need to find their relief in the United States. Many of them want to because they have family ties to the region, to the country, or it seems as though it's the biggest economy that is the shortest geographic distance from them. But there are other countries in Latin America and elsewhere in the world, that could also provide the same kind of relief that the United States or Mexico can. And we can only engage in that conversation if the United Nations has a bigger seat at the table. And so I would just offer that the United States certainly does, or the United Nations certainly does have a role to play. And I would encourage the Biden administration to really seek opportunities with UNHCR and UNODC, as you mentioned, in trying to really tackle the issues, both in terms of the proximate causes for migration, but also in addressing more broader issues relating to the root causes. FASKIANOS: Wonderful. Well, we couldn't get to all the questions but we covered a lot of ground. Thank you, Paul Angelo for this. It's great to have you at the Council. And to all of you for your terrific questions, and comments, and the work that you're doing in your communities. We appreciate it. You can follow Paul Angelo on Twitter @pol_ange. You can also find his op-eds, and testimonies, and other pieces on our website CFR.org. So I encourage you to go there. Please follow us on Twitter @CFR_Religion. And, as always, send comments, suggestions to us at [email protected]. We love hearing your suggestions of future topics we should be covering. So thank you all again for doing this, for being with us, and stay well, and stay safe.

-

Why Central American Migrants Are Arriving at the U.S. BorderThousands of people are arriving at the U.S. southern border after fleeing the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. President Biden is reviving efforts to tackle the problems that are prompting them to migrate.

-

Another Israeli Election, U.S.-Mexico Border Crisis, and MoreIsrael holds its fourth election in two years, the United States faces a mounting migration crisis at its border with Mexico, and Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, meets with regional premiers.

-

Making Anti-Corruption Reforms Stick in the Northern TriangleThe Biden administration made a bold commitment to support the region’s prosecutors in their fight against impunity. But corrupt courts, business associations, and legislatures could derail the progress if they are not reformed in time.

-

Migrants at the U.S. Border: How Biden’s Approach Differs From Trump’sPresident Biden is adopting a different approach than his predecessor to an increasing number of migrants who are arriving at the southern border after fleeing hardship in their home countries.

-

Breaking Down Biden’s Immigration Actions Through AbbreviationsAbbreviations are a fixture of U.S. immigration policy. CFR explains some of the most commonly referenced agencies, policies, and programs, and what President Biden is doing about them.

-

Ethnic and Religious Violence Worsen in KadunaKaduna is increasingly the epicenter of violence in Nigeria, rivaling Borno state, the home turf of Boko Haram. In rural areas, conflicts over water and land use are escalating, and Ansaru, a less prominent Islamist group, is active. Over the past year, some four hundred people were abducted for ransom in the state by criminal gangs; more than two hundred violent events resulted in nearly one thousand fatalities, and some fifty thousand are internally displaced. These estimates apply to the state as a whole, including the city of Kaduna, the capital of the state. The city of Kaduna has long been a center of political, ethnic, and religious violence. The city has undergone ethnic "cleansing," with Christians now concentrated in south Kaduna city and the Muslims in the north. Since the end of military rule in 1998–99, Kaduna city saw election-related violence that soon turned into bloodshed along ethnic and religious lines. Like the Nigerian state, the city of Kaduna is a British colonial creation orchestrated by Lord Frederick Lugard, first governor general of an amalgamated Nigeria. He established Kaduna as the British administrative capital of the northern half of the country, to be situated on the railway that linked Lagos and Kano—then, as now, Nigeria's largest cities. As the administrative capital of the north, Kaduna acquired some of the accoutrements of British colonialism, including a race track, polo, and expat club. A number of foreign governments, including the United States, established consulates in Kaduna, an "artificial," planned city reminiscent of the current capital, Abuja. The British encouraged Muslims incomers to settle in the north and Christians in the south. In part because of the railway connections, Kaduna became an important manufacturing center, especially for textiles. An international airport was eventually built. But the last half-century has not been kind. Nigeria moved from four regions, of which Kaduna was the capital of the largest, to thirty-six states. The establishment of a new national capital at Abuja led to the departure of consulates and many international business links, and, while the airport survives, most regional air traffic goes to Abuja. The textile industry and most heavy manufacturing have also collapsed, the consequence of erratic economic policy, underinvestment, and foreign competition. The national railway network became moribund and is only now being restored by the Chinese. Yet Kaduna's urban population has exploded. In the 2006 census [PDF], the state capital's population was 760,084; now, the estimate is closer to 1.8 million. Agricultural output has collapsed, the result of climate change and the breakdown of security, resulting in waves of migrants into a city that does not have the infrastructure to accommodate them. Very high levels of unemployment (nobody really knows how high), a youth bulge, and shortage of housing makes the city a veritable petri dish for violence that acquires an ethnic and religious coloration. Further, the traditional Islamic institutions to be found elsewhere in the north were either never present in the British-founded city or have been weak. Hence, in the city of Kaduna, violence is multifaceted in origin, and no one strategy is likely to bring it under control. At best, small steps to improve services to the population could buy some time for the larger political, economic, and social changes that will be necessary to restore the health of the city.

-

Arthur C. Helton Lecture: Migrants and the U.S. Southern BorderPanelists discuss the humanitarian concerns facing migrants at the U.S. southern border, including how the pandemic is affecting refugees and asylum seekers, and the future of immigration under the new administration. The Arthur C. Helton Memorial Lecture was established by CFR and the family of Arthur C. Helton, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who died in the August 2003 bombing of the UN headquarters in Baghdad. The Lecture addresses pressing issues in the broad field of human rights and humanitarian concerns.

-

Transition 2021: How Will Biden Handle Latin America?Paul J. Angelo, CFR fellow for Latin America Studies, and Shannon K. O'Neil, vice president, deputy director of studies, and Nelson and David Rockefeller senior fellow for Latin America Studies at CFR, sit down with James M. Lindsay to discuss the incoming Biden administration’s likely approach to Latin America.

-

2020: The Year’s Historic News in GraphicsExtreme natural occurrences. Police brutality and racism. A global pandemic. CFR breaks down 2020’s biggest news with graphics.

-

The Year the Earth Stood StillThe COVID-19 pandemic brought travel around the world to an abrupt halt in 2020. Nations are still trying to grasp the consequences, and restarting movement could take years.

-

U.S.-Mexico Partnership Will Get More PricklyBeyond his bluster on migration and trade, Donald Trump actually asked little of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. That will change under Joe Biden.

-