- Experts

- Election 2024

-

Topics

FeaturedIntroduction Over the last several decades, governments have collectively pledged to slow global warming. But despite intensified diplomacy, the world is already facing the consequences of climate…

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

FeaturedThe rapidly changing landscape of foreign influence demands a new approach, argues Senior Fellow for Global Governance Miles Kahler. Countering malign influence from abroad will require a stronger democracy at home.

Council Special Report by Miles Kahler October 23, 2024 Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedThis symposium was created to address the broad spectrum of issues affecting Wall Street and international economics. It was established through the generous support of Council board member Stephen C…

Virtual Event with Emily J. Blanchard, Matthew P. Goodman, David R. Malpass, Elizabeth Rosenberg, Janet Yellen, Michael Froman and Rebecca Patterson October 17, 2024 Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies

- Related Sites

- More

Politics and Government

-

The President’s Inbox Recap: Taiwan’s Presidential ElectionTaiwan’s presidential election may increase U.S.-China tensions.

-

What to Do About CoupsNothing may seem more obvious to supporters of democracy than the need to oppose, punish, and deter coups. But defining a coup, let alone reacting sensibly to one, is difficult for many democratic governments. The dictionary definition of a coup is reasonably clear. Merriam Webster’s definition is “a sudden decisive exercise of force in politics and especially the violent overthrow or alteration of an existing government by a small group.” Similarly, Cambridge says a coup is “a sudden illegal, often violent, taking of government power, especially by part of an army.” In practice, however, these definitions are trickier. What Is U.S. Law? For nearly four decades, U.S. law has required that the U.S. government react to coups by immediately cutting off many forms of foreign assistance. In 1985, a provision of law was adopted saying assistance to the government of El Salvador would be stopped if there were a coup, and in the following year Congress expanded that provision to “any country.” While initially the law referred to “military coups,” the provision was broadened to include any form of “coups d’état” in 2010 and broadened again in 2012 to add any “actions in which the military plays a decisive role.” Today, Section 7008 of the State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations legislation reads as follows: Prohibition.--None of the funds appropriated or otherwise made available pursuant to titles III through VI of this Act shall be obligated or expended to finance directly any assistance to the government of any country whose duly elected head of government is deposed by military coup d’etat or decree or, after the date of enactment of this Act, a coup d’etat or decree in which the military plays a decisive role…. Under the statute, assistance would be resumed if and when the secretary of state “certifies and reports to the appropriate congressional committees that subsequent to the termination of assistance a democratically elected government has taken office.” Applying U.S. Law: Calling a Coup a Coup Has Been a Problem These laws may seem straightforward but putting them into practice has been difficult. There are occasions when the U.S. government acted with dispatch when coups occurred and cut off aid. The Congressional Research Service [PDF] reported in 2023 that “during the past decade, the provision was temporarily in effect for the following countries: Fiji (2006 coup; lifted after 2014 elections), Madagascar (2009 coup; lifted after 2014 elections), Guinea-Bissau (2012 coup; lifted after 2014 elections), Mali (2012 coup; lifted after 2013 elections), and Thailand (2014 coup, lifted after 2019 elections).” But it also noted that the “coup provision” was not applied in these cases: Honduras in 2009, Niger in 2010, Egypt in 2013, Burkina Faso in 2014, Zimbabwe in 2017, Algeria in 2019, and Chad in 2021. The old legal saying that “hard cases make bad law” seems to apply to the “hard case” of the 2013 coup in Egypt, where, after a period of public unrest, the military overthrew the democratically elected government of Mohammed Morsi. Egypt was suspended from the African Union, which has an anti-coup regulation. The European Union (EU) and France immediately labeled the action a coup. But the United States, which unlike the EU and France actually has a law on the books requiring suspension of aid when there is a coup, nevertheless did not join them. As one news story put it at the time, “U.S. Ducks Decision on Egypt Coup.” That story quotes State Department Press Secretary Jen Psaki explaining that “the law does not require us to make a formal determination...as to whether a coup took place, and it is not in our national interest to make such a determination.” She also said, when questioned about why the Obama administration was not using the term “coup,” that “each circumstance is different. You can’t compare what’s happening in Egypt with what’s happened in every other country.” She added that, in huge demonstrations against the Morsi government that preceded the coup, “there were millions of people who have expressed legitimate grievances. A democratic process is not just about casting your ballots…There are other factors including how somebody behaves or how they govern.” This implicit criticism of the Morsi government was almost a defense of the coup, truly a “hard case” pushing the U.S. government into a position difficult to defend. The United Kingdom also refused to label the coup a coup, and British Prime Minister David Cameron explained why: the United Kingdom “never supports” intervention by the military, he said, “but what we need to happen now in Egypt is for democracy to flourish and for a genuine democratic transition to take place.” In plainer English, Cameron was arguing that once a coup happens, it is spilled milk and governments have to be realistic. The question at that point is how to work with the country (and the coup leaders) and try to get things back on the democratic track. Psaki took a different and much worse line: Morsi had been a bad and increasingly unpopular ruler of Egypt, so a coup was perhaps inevitable and anyway Morsi was no model democrat. Fair enough, but U.S. law was clear: it speaks of a “duly elected government,” and surely Morsi’s was that. This is one significant flaw in the U.S. law: it is not so rare that a leader is “duly elected” but then subverts the democratic system to stay in power. Morsi was accused of doing it, as was Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Father Aristide in Haiti, and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, to take but three examples. Why should overthrowing a would-be dictator, or an elected president who destroys democracy and makes another free election impossible, be treated exactly like a military coup that ousts a truly democratic government? What is increasingly clear is that the “coup provision” in U.S. law, instead of strengthening U.S. opposition to coups, has often led the U.S. government to duck even calling a coup by its proper name. The most recent case is the coup in Niger on July 26, 2023. It is a classic case: a democratically elected civilian president was removed and detained by the military. The EU, France, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) immediately labeled this a coup. But the United States has refused to do so, leading to a Washington Post editorial in August entitled “U.S. Should Call Niger’s Coup What It Is: A Coup.” Why has the United States refused? The Post theorizes that “administration officials [are] hoping that diplomacy might still persuade the soldiers to return to their barracks….” But as the weeks go by, this hope is increasingly unrealistic. So why not label the coup a coup now—better late than never? Perhaps because the Biden administration wishes to continue some important counterterrorism programs in Niger even under its new military junta. The solution seems obvious: call the coup by its proper name but say that U.S. national security requires continuing the relationship with the Nigerien military. “National Security” Waivers The “national security waiver” is a common procedure in the human rights context. For example, U.S. law states that “no security assistance may be provided to any country the government of which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights…unless the President certifies in writing to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate that extraordinary circumstances exist warranting provision of such assistance.” In accordance with this provision of law, the Biden administration has withheld portions of U.S. military assistance to Egypt on human rights grounds but delivered other portions. Another similar provision of law prohibits “any training, equipment, or other assistance for a unit of a foreign security force if the Secretary of Defense has credible information that the unit has committed a gross violation of human rights,” but adds that the provision “shall not apply if the Secretary of Defense, after consultation with the Secretary of State, determines that…the equipment or other assistance is necessary to assist in disaster relief operations or other humanitarian or national security emergencies.” In 2023, Congress for the first time added a national security waiver to the provisions of law requiring a cut-off of assistance when a coup overthrows a “duly elected head of government.” The new provision states that the secretary of state “may waive the restriction in this section…if the Secretary certifies and reports to the Committees on Appropriations that such waiver is in the national security interest of the United States….” Thus, the national security waiver is available today in the United States, as it was not after the coup in Egypt in 2013. The Biden administration is able to take the Washington Post’s advice in the case of Niger and in future coup cases. Be honest about what has happened but say that the United States has national security interests that—at that moment and in that case—override its preference for democratically elected governments and against military coups. Are Anti-Coup Laws Good Policy? Has the forty-year U.S. experiment with anti-coup laws advanced the cause of democracy? Has the law been honored more in the breach than in the observance? Has the United States now found a happy equilibrium or a poor balance? It is impossible to say how many coups, if any, were avoided by the prospect of a cut-off in U.S. assistance. Given the uncertainty of whether the United States would call a coup a coup and actually cut off aid, it seems unlikely that there were many. The law surely serves notice from Congress to the executive branch that it takes coups against elected governments seriously and does not expect them to be overlooked or downplayed when the State Department makes decisions about foreign aid. But Congress, which must appropriate foreign aid, always has the ultimate say and can cut off aid to any recipient government whenever it wants. The great advantage of the anti-coup provision is speed, because it can be invoked immediately, while new legislation cutting off aid may take a year to pass. For a new military junta, the prospect of a cut-off next week surely means more than one a year or more away. But the addition of a national interest waiver to the “coup cut-off provision” after thirty-eight years suggests that Congress has finally acknowledged what history shows: the cut-off provision is a strait jacket for the State Department. Its attempts to escape the law’s provisions may do more harm to democracy than the good the existence of the law accomplishes. At least the waiver provision now allows the State Department to be honest about the fact of a coup, and then decide how to weigh security interests against the desire to protect democracy. Has a happy medium been reached? Perhaps, but the waiver provision now risks creating two classes of countries: those significant enough to warrant a waiver and those so unimportant to the United States that the waiver is not invoked. And similarly, it may create two classes of coups: those deemed acceptable because the United States did not like the previous (elected) government, and those that overthrew a president the United States supported. Or perhaps the executive branch’s future waiver decisions will be based on hard realpolitik: where a coup is reversible it will suspend aid, but where it seems the new military government is there to stay aid will be continued, accompanied by a wagging of fingers and more press guidance about the importance of democracy. Coups occur irregularly but they are an apparently incurable disease, so the new law with its waiver provision will be tested in time. One can think of an addition to the new law—containing now the mandatory cut-off but also the waiver provision—that requires (a) that the State Department report to Congress (in secret testimony if need be) within one week of an apparent coup; (b) that it make a determination: coup or no coup; and (c) that State defend the policy it is following, explaining how it is weighing the value of U.S. support for democracy against what it sees as U.S. national security interests. The current law no doubt expresses opposition to coups, but it has not led to candor in the execution of U.S. foreign policy. That is an ingredient worth adding, and a part of democratic government as well. This publication is part of the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy.

-

Taiwan’s Pivotal Elections, Apple Battles Regulations, Davos Addresses World Risks, and MoreTaiwan holds its presidential and legislative elections, which have major geopolitical consequences for both the United States and China; tech giant Apple deals with patent infringement allegations while more governments consider regulations on tech; the fifty-fourth World Economic Forum Annual Meeting hosts global business and political leaders in Davos, Switzerland, to address multiple crises such as conflict, climate change, and misinformation; and France appoints Gabriel Attal, the country’s youngest and first openly gay prime minister.

-

Bangladesh’s Sham Election and the Regression of Democracy in South and Southeast AsiaBangladesh’s unfree election is part of a larger trend of democratic regression in South and Southeast Asia.

-

Religious RumblingsNigerians are increasingly frustrated with the Bola Tinubu administration, none more so than Nigerian Christians.

-

Taiwan’s Presidential Election, With David SacksDavid Sacks, a fellow for Asia studies at CFR, sits down with James M. Lindsay to discuss the potential geopolitical consequences of Taiwan’s presidential race.

-

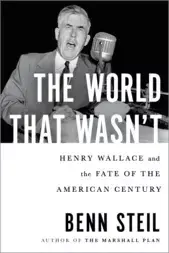

The World That Wasn’t

![]() A dramatic and powerful new perspective on the political career of Henry Wallace—a perspective that will forever change how we view the making of U.S. and Soviet foreign policy at the dawn of the Cold War.

A dramatic and powerful new perspective on the political career of Henry Wallace—a perspective that will forever change how we view the making of U.S. and Soviet foreign policy at the dawn of the Cold War. -

The State of Democracy Around the WorldOver four billion people in more than three dozen countries will have the opportunity to vote for new leadership in elections in 2024. Panelists discuss the strength of democracies in the year ahead and the challenges they face, including polarization, nationalism, and curtailed political freedoms. This meeting part of the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Meeting Series on Democracy.

-

Election 2024: The Third Anniversary of the January 6 Attack on the U.S. CapitolEach Friday, I look at what the presidential contenders are saying about foreign policy. This Week: Americans are divided over the meaning of January 6.

-

History Breeds Skepticism in the DRC’s Electoral ResultsAttempts to promote “stability” in 2019 bear predictable consequences in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s most recent election.

-

Taiwan’s Early Warning for the Future of TechTaiwan faces online threats in the run up to its January 13 election. Companies, governments, and civil society need to work together to defend against the growing influence of digital authoritarianism in Taiwan and worldwide.

-

The Organized Crime Threat to Latin American DemocraciesGovernments have learned to manage many threats, but they are failing to curb the growing power of organized crime.

-

The Destructive Drive in African PoliticsThe descent into normlessness in various African countries calls for a new scholarly and policy approach.

-

Ten World Figures Who Died in 2023Ten people who passed away this year who shaped world affairs for better or worse.

Online Store

Online Store