Waiting for Growth: California, Wisconsin, and Scarcity Politics

Many years ago I was attracted to the idea that advanced economies could gradually move from a relentless focus on economic growth to a “steady state” in which they would grow only slowly, if at all. It all seemed quite logical – as societies became generally wealthy, as population growth slowed, and as non-renewable resources were further depleted, more modest rates of growth would be more sustainable and perhaps even conducive to a higher quality of life that was less focused on the next percentage point of growth.

It was, in retrospect, rather naïve. The reason is this: A successful slow growth society would require a population that believed in the fairness of how that fixed wealth was distributed. And that appears to be nearly impossible. Even in a country like Japan, which is something of a model here, slow growth over the past two decades has brought with it a near permanent crisis of political instability. In Europe, anemic growth coupled with high borrowing in many countries to pay for an unsustainable level of government services has undermined what appeared to be an enlightened arrangement in which the richer northern countries helped along their poorer southern neighbors.

And in the United States, the dismal growth of the past five years is similarly unraveling the social compact. Tuesday night’s elections were only a small harbinger of what is likely to come. In debt-plagued California, where public schools may be cut by three weeks to save money and the nation’s best public university system is being starved, voters in San Jose and San Diego voted to roll back generous pension benefits for current and retired workers, in effect tearing up contracts that had been signed in an era when strong growth was taken for granted. With state taxes and unemployment in Californian both already among the nation’s highest, voters are set on clawing back scarce dollars from someone else.

Similarly, voters in Wisconsin returned Republican governor Scott Walker, whose efforts to cut wages and benefits for public workers had resulted in a recall campaign that split the state into near warring factions. Walker has promised to try to heal the wounds, but economic growth in Wisconsin has been weaker than in most of the rest of the country. Unless that changes, the battles over distribution will only get worse.

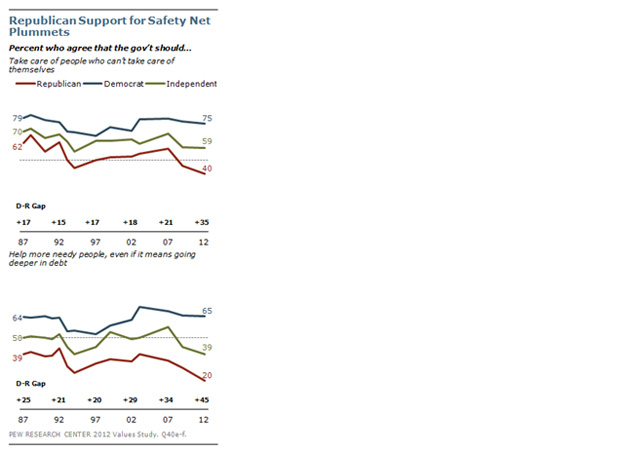

At the national level, the big election-year debates over taxes and government spending reflect increasingly deep divisions over how to distribute wealth in an economy that’s barely growing. The newly released Pew survey of “Trends in American Values” shows a widening gulf between Democrats and Republicans, especially since the onset of the recession in 2007. And almost all of the increased polarization has occurred over the past decade, during which most Americans saw losses in real income.

One question asked Republicans, Democrats, and Independents whether “government should take care of people who can’t take care of themselves.” Among Republicans, 62 percent said yes in 1987, but today just 40 percent think so. Most of the decline has occurred in the past five years. On another question, whether “government should help more needy people, even if it means going deeper into debt,” two-thirds of Democrats said yes, roughly the same as in 1987. But among Republicans support fell from 39 percent to 20 percent, and there has been a big drop among Independents as well.

Source: "Trends in American Values: 1897-2012," Pew Research Center

These numbers are particularly worrisome because the federal government has yet to actually make any of the tough budget decisions it must inevitably make. New figures released by the Congressional Budget Office this week forecast that, if Congress remains on its current tax and spending path, federal debt will continue to rise from 73 percent of GDP this year to 93 percent by 2022 and nearly 200 percent by 2037.

Is there a way out? Only one that’s plausible – strong, sustained economic growth. Most of the fights over limited resources will become far easier to resolve if the resources aren’t so limited. Both parties pay lip service to this by packaging their preferred distribution of wealth as growth enhancing. Republicans claim smaller government and low taxes on the wealthy will accelerate economic growth; Democrats claim stimulus spending and targeted subsidies will jumpstart growth. But in neither case is growth actually the priority – it is rather a sort of residual effect of policies favored on distributional grounds.

That needs to change, and soon. Because as we are seeing, the steady state economy turns out to be anything but.

Online Store

Online Store