New Questions about Chinese Innovation

More on:

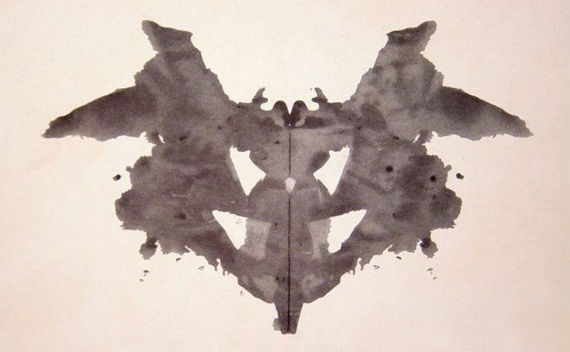

John Kao has a six-part series over at CNN GPS on China as an innovation nation. Just back from a study trip, Kao is a little breathless in his admiration of Chinese policymakers’ embrace of innovation. At least in my view, he doesn’t add very much to the debate about how innovative the country truly is. In fact, he seems pretty torn himself since he sees China’s ambitious planning and government intervention as great both a strength and a major pothole. The whole series is a kind of Rorschach test: those already skeptical will find further evidence of weakness in the Chinese system, those sure of China’s rise will find some new awe-inspiring stories.

As one of the skeptical voices, I began amassing new evidence of what I call the weakness in the software of innovation—the social, political, and cultural institutions and understandings that help move ideas from lab to marketplace. But I’ve begun to wonder how useful that is. Sure, there have been some good stories out the last two weeks which suggest that the process of building an innovation system will be slow and uneven—60 percent of state R&D funds are lost to corruption; the president of China Agricultural University accused of plagiarism; and an outspoken neuroscientist rejected from the Chinese Academy of Sciences—but this back and forth must be getting a little stale. Perhaps we can all agree that there are major weaknesses embedded in apparent strengths and that trends are clearer than outcomes.

In place of the "China is or isn’t innovative debate," let me suggest three other questions to address:

- Do we need new metrics of innovation? As with so many things, China is an extreme version of what is widespread. Despite constant references to a Chinese or American innovation system, the globalization of innovation means that the state is only one player in a truly intertwined global system. Companies, university R&D networks, alumnae groups, and returnees all play a major role. Measurements of innovation—how much the U.S. spends on R&D, how many patents Chinese firms filed last year—remain grounded in the old model.

- Who benefits from current models and what happens if they change? American companies have benefited from a system where they can take advantage of research produced in the U.S. and cheap labor in China. American and Chinese consumers have benefited from cheaper consumer goods and cool electronic gizmos. American workers have not done as well, and as we enter what is bound to be a contentious election season, the question is how long can that last. What happens if China moves up the product chain? Who benefits then?

- Can the two systems work together? Kao calls for greater cooperation, but is a bit vague on where that will happen, calling for the two sides to take a "fresh look at innovation together." I am more skeptical. Just a few years ago, many were pointing to new energy as a potential source of cooperation, but that has emerged as another source of contention (see here for the latest case of possible IPR theft by a Chinese company). The problem is not that we don’t understand Chinese goals; it is that the United States does not agree with how China is pursuing them. In his last post, Kao called his approach "guarded openness" with a clear focus on U.S. interests. That sounds about right to me.

This is just a preliminary list. What else should be on there?

More on:

Online Store

Online Store