New Argentine President Macri’s Economic Challenges

More on:

Mauricio Macri, mayor of Buenos Aires and leader of the Cambiemos coalition, won yesterday’s presidential run-off, becoming the first non-Peronist president in nearly fifteen years. From his start on December 10 he will face several severe economic challenges:

1. Dwindling foreign reserves

Official foreign reserves total just $26 billion. Of this, over half reflects swap agreements with China and other commitments, leaving just $11 billion in liquid assets. This limited buffer will likely decline as the summer progresses, until the soybean harvest begins in March. Though the season looks bountiful, soy prices are now just half 2012 levels, lessening the benefit for foreign exchange coffers. These low levels will calculate into the government’s negotiations with holdout creditors, led by Paul Singer’s NML Capital, who collectively hold $7.9 billion in defaulted Argentine bonds. Any quick solution will require the foreign reserve benefits of settling—including inflows of new capital—to outweigh the potential outflows.

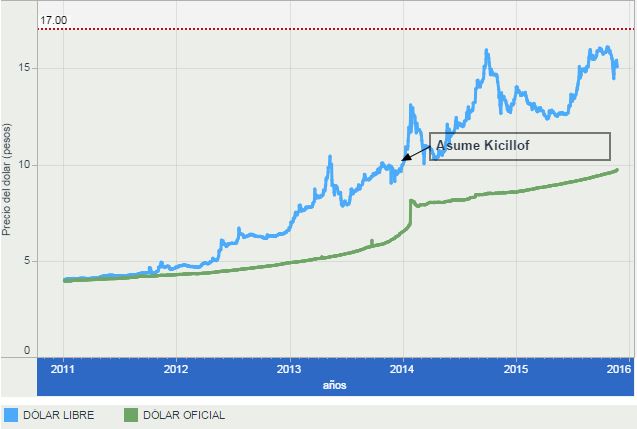

2. Diverging exchange rates

The difference between the official rate—9.5 pesos to the dollar—and the black market or “blue dollar” near 15—leads to local economic distortions and discourages foreign investment into the economy. Macri has already promised to lift currency controls, an important step towards letting markets again work. But it will spur inflation—which independent economists estimate at over 25 percent already.

The recent sale of $15 billion’s worth of dollar denominated futures contracts by the central bank will make a devaluation more costly for the government, adding potentially $7 billion to the public debt burden.

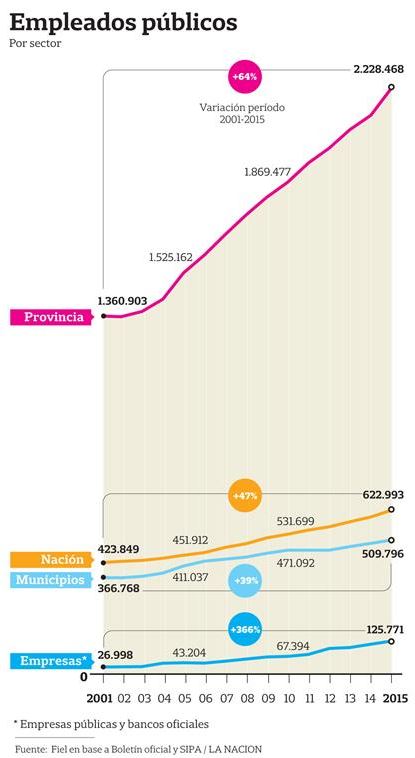

3. Growing fiscal deficit

The added public debt burden comes at a time when the government is already running a fiscal deficit equal to 7 percent of GDP (the highest since 1982). This reflects the greatly expanded state—double its size as a percentage of GDP from when Nestor Kirchner took office in 2003. A big portion is public salaries—the public sector now employs 3.7 million of the 17 million members of the economically active population.

4. Slower economic growth and rising unemployment

The economic outlook for Argentina is grim. The International Monetary Fund projects less than 1 percent growth for the next several years due to falling commodity prices, stagnant industrial production, and domestic economic distortions. Argentina’s largest trading partner, Brazil, faces its deepest recession since the global financial crisis, and China’s slowdown, though less extreme, has weakened demand for Argentine commodities. Private sector employment is now falling, down 1.3 percent year on year.

5. Tough politics

In addition to the difficult external climate, Macri faces tough domestic politics. His coalition claims some 90 of the 257 seats in the lower house (his own party 18), meaning any legislative reforms will require Peronist support.

---

Argentina holds strong advantages—including a plethora of untapped mineral deposits and the world’s second-largest shale gas reserves. Its agricultural bounty remains, and an overhaul of punitive export taxes on corn and soy should bring in more investment, boosting productivity and output, as Argentina’s crops are profitable even at lower global prices.

Macri will benefit from his promises of change, and a few quick market friendly moves. His technocratic team—many trained abroad—understands this, as does the president-elect. Investors are already betting on his turnaround success—pushing government bonds up 30 percent, and the Merval (Argentina’s benchmark stock index) up over 60 percent since the year’s start. The new government looks to entice back the estimated $225 billion Argentines have sent abroad through tax amnesties and other policies. Even if a part comes back, combined with new foreign direct investment and loans (assuming Argentina comes back to world markets), this money could help revive Argentina’s over $500 billion economy.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store