How to Solve the Global Steel Glut

April 19, 2016 10:48 am (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

More on:

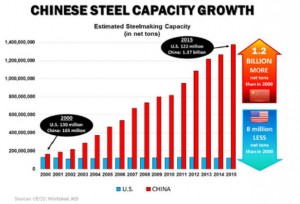

The steel industry is once again in crisis. Led by China, global steelmaking capacity has doubled in the past 15 years, while demand has slumped. The consequences in many countries are falling prices, idled production, bankruptcies and job losses. U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman last week called it "a truly global challenge".

Some 12,000 U.S. steelworkers have lost their jobs in the past year, nearly 10 percent of the total workforce. Britain's largest steel producer, Indian-owned Tata Steel, is likely to close unless it finds a buyer, with 40,000 jobs on the line; Australia's two largest producers are already in bankruptcy. The OECD club of developed economies hosted a high-level meeting on April 18 with China and other major steel producers but the gathering failed to agree measures to tackle excess capacity amid arguments over who was to blame.

Protectionist wars are already breaking out. The United States has imposed a slew of anti-dumping orders restricting steel imports from Asia, Europe and Latin America. Europe has limited some steel imports and is considering more curbs. China recently slapped tariffs on a smaller category of European steel imports. And USTR Froman last week warned of further "serious trade responses" if China does not cut its steel production and stop exporting the surplus.

The problems in the steel industry are far from new. A 1988 book "Steel and the State: Government Intervention and Steel's Structural Crisis" noted in its opening chapter that the industry had faced "a crisis of overcapacity" since the mid-1970s. That overcapacity was a consequence, the authors argued, of "pervasive intervention by governments in the market"—in particular large subsidies to steel mills that resulted in production far in excess of what the market would otherwise dictate.

Today, China is by far the worst offender. In 2000, the United States and China produced about the same amount of steel—135 million metric tons (MMT) in the United States, and 165 MMT in China. Since then, China has added an extraordinary 990 MMT of steelmaking capacity—more steel than the entire world was consuming in 2000. This was not driven by market opportunities but rather by government subsidies aimed at pumping up the economy through investment and job creation; China's major steel firms reportedly lost nearly $10 billion last year and are groaning under their debt load. Other countries, including Korea, Turkey and India, have also boosted production. U.S. steel capacity fell over the same period, as did Europe's.

If the United States, Japan, the European Union, India, Turkey, Russia, Korea and Brazil all stopped making steel tomorrow, there would still be enough to supply the global market.

One of the reasons free trade is under such attack in the United States and some other countries is that the classic free trade argument—that the market will sort this mess out to everyone's benefit -- simply does not hold true in such a distorted sector. If nothing is done, some of the most efficient steel plants in the world will go under and the heavily subsidized, unprofitable ones in China and elsewhere will survive.

But the classic U.S. and European response—to throw up trade barriers in the form of anti-dumping tariffs—is not terribly helpful either. Temporary tariffs can give some breathing room to their steel industries. But they come too late, often when the companies are teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. And breathing room for what? If there is no big reduction in steel capacity worldwide, the problem will either be shuffled off to other countries or will re-emerge when the tariffs expire. In the meantime, big steel-using industries like automobiles and shipbuilders will face higher costs than their competitors in countries where steel markets are less protected.

The only effective solution is a hugely difficult one—following the OECD prescription and negotiating an international agreement in which steel producing nations agree to an orderly, shared reduction in capacity to balance supply and demand better. But such a deal is almost impossibly difficult to reach. Steel-producing nations tried this seriously once before, in the early 1990s, when the OECD hosted talks on a "Multilateral Steel Agreement" (MSA). The U.S. steel industry had hoped that an MSA would "end government subsidies, cartels and cartel-like behavior and other anti-competitive practices in steel trade and open up all steel markets worldwide to full, market-based competition."

But the politics were simply too hard. "Reducing capacity" is a lovely euphemism for shutting factories and firing steelworkers, and few countries wanted to sign on. And the scale of the problem was much smaller in the 1990s. Today, China has said it might be willing to cut steel capacity by 10 percent or so. Its behavior suggests otherwise, as capacity has continued to grow. And even if Beijing did trim output, it would be a token gesture given the scale of the problem.

Yet there seems little choice but to try again to craft such a deal, despite the failure of Monday's OECD meeting. The alternative—an escalating global trade war in a vital industrial sector—would be harmful to every country involved.

This article originally appeared on asia.nikkei.com.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store