More on:

Former ambassador Donald Gregg has labeled North Korea “our longest-running intelligence failure.” North Korea’s long-running quest to keep the veil over the “hermit kingdom” has vexed scholars who have tried to gain empirical data on how North Korea works. However, a project to map out almost two decades of non-governmental engagement with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) reveals that it has more foreign exposure than most people think, and that the number of outsiders visiting sanctions-weary North Korea for tourism and business reasons has been going up sharply.

A clear understanding of North Korea’s history of engagement and its preferences regarding who it works with and how it works is essential for practitioners who want to engage with North Korea, as well as for analysts who seek to understand how the regime pursues its policies. It may also provide useful information regarding how to craft more effective policies for engaging North Korea and what North Korea seeks most from the outside world. For this reason, www.engagedprk.org, an interactive map showing international projects and sectors inside North Korea since 1995, is an effective tool for chronicling almost two decades of international efforts to work inside North Korea. The effort to capture engagement with North Korea was conceptualized and undertaken by Jiehae Blackman since 2011, with support from Reah International and the U.S. Institute of Peace.

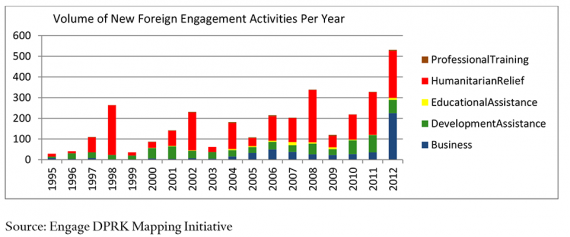

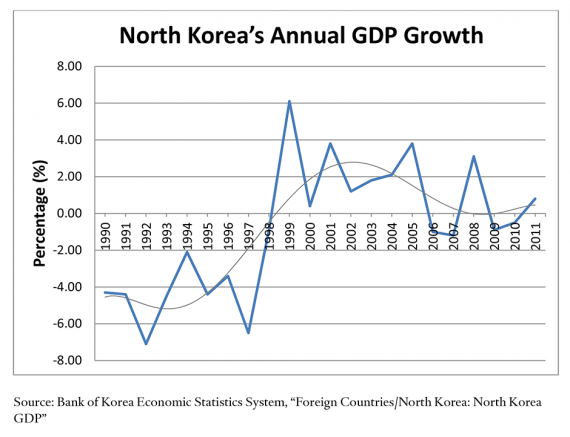

The chart above shows upticks in the provision of humanitarian relief to North Korea in the late 1990s and again between 2006 and 2009, which correspond to periods of economic distress in North Korea’s domestic economy. This data is not surprising because North Korea’s external engagement began as a safety valve to relieve internal distress resulting from acute humanitarian needs. A full-blown famine in North Korea and domestic production failures in the mid-2000s created internal system stresses that necessitated North Korea’s reliance on outside aid and opened doors for humanitarian aid groups to come in.

These humanitarian crises also created opportunities for some groups to pursue long-term development assistance projects inside North Korea to address critical needs in infrastructure and public health. Despite the passing of North Korea’s immediate food crisis, longer-term development projects implemented in the late 1990s have continued as a significant portion of DPRK’s interaction with the outside world, with around thirty projects annually continuing since the year 2000. These projects, primarily European in origin, have persisted even during periods of political tension, providing benefits to North Korea and keeping open a window for international engagement with the North.

However, a new pattern of external engagement with North Korea has emerged since the early 2000s with a steadier growth of about twenty to thirty new “business” projects starting in North Korea each year since 2004. Last year, the business sector took off, with the number of new entities trying to do business with North Korea increasing dramatically. Many of these ventures support North Korean efforts to promote international tourism, reflecting the fact that tourism has become the North Korean leadership’s priority, perhaps because it is perceived as a safe way for the state to generate international currency without necessarily leaving a lasting impact on the North Korean people. Nonetheless, the jump in external “business” activities with North Korea reveals one means (in addition to Sino-DPRK trade) by which North Korea can gain needed foreign currency without regard to narrowly focused UN sanctions resolutions, which block only transactions related to North Korea’s nuclear and missile program.

North Korea’s growing interest in “business” with the international community is a fact that will drive opposing conclusions in the ongoing policy debate over North Korea. Some will argue that doing business with North Korea is precisely the bait that will entice North Korea to bite on the hook of economic integration and eventually neutralize North Korea’s motives for pursuing a nuclear program. On the other hand, others will argue that North Korea continues to use hard currency earnings to subsidize its other programs, in which case North Korea’s business breakout cannot be good news for policymakers who want to force North Korea into a “strategic choice” in favor of denuclearization. At the very least, it may reveal why North Korea’s leadership may believe that its dual emphasis on economic and nuclear development, announced as its main “strategic line” at a Central Committee meeting of the Workers’ Party of Korea last March, may provide an opportunity to muddle through.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store