- China

- RealEcon

-

Topics

FeaturedInternational efforts, such as the Paris Agreement, aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But experts say countries aren’t doing enough to limit dangerous global warming.

-

Regions

FeaturedIntroduction Throughout its decades of independence, Myanmar has struggled with military rule, civil war, poor governance, and widespread poverty. A military coup in February 2021 dashed hopes for…

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

-

Explainers

FeaturedDuring the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised that his administration would make a “historic effort” to reduce long-running racial inequities in health. Tobacco use—the leading cause of p…

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky, Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

-

Research & Analysis

FeaturedAmazon Best Book of September 2024 New York Times’ Nonfiction Book to Read Fall 2024 In this “monumental and impressive” biography, Max Boot, the distinguished political columnist, illuminates…

Book by Max Boot September 10, 2024

-

Communities

Featured

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

-

Events

FeaturedPlease join us for two panels to discuss the agenda and likely outcomes of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Summit, taking place in Washington DC from July 9 to 11. SESSION I: A Conversation With NSC Director for Europe Michael Carpenter 12:30 p.m.—1:00 p.m. (EDT) In-Person Lunch Reception 1:00 p.m.—1:30 p.m. (EDT) Hybrid Meeting SESSION II: NATO’s Future: Enlarged and More European? 1:30 p.m.—1:45 p.m. (EDT) In-Person Coffee Break 1:45 p.m.—2:45 p.m. (EDT) Hybrid Meeting

Virtual Event with Emma M. Ashford, Michael R. Carpenter, Camille Grand, Thomas Wright, Liana Fix and Charles A. Kupchan June 25, 2024 Europe Program

- Related Sites

- More

Asia

Japan

-

Trump Versus Abe: The Trade End GameU.S. president struggling to squeeze tough deal out of Japan.

-

The Japanese Emperor’s Role in Foreign PolicyWith Emperor Akihito’s historic abdication approaching, here’s a look at his accomplishments and what to expect from the next emperor, Crown Prince Naruhito.

-

Sri Lanka Mourns Its Losses, Spain Holds an Election, and MoreSri Lankans mourn after the Easter Sunday attacks, Spain holds a snap election, and Japanese Crown Prince Naruhito ascends the throne.

-

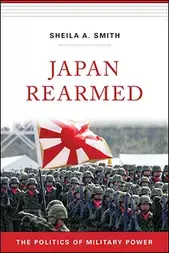

Why Japan Is Reassessing Its Military PowerFollowing World War II, Japan’s U.S.–imposed constitution renounced the use of offensive military force. But a nuclear North Korea and an increasingly assertive China have the Japanese rethinking that commitment. Learn more about Japan's reassessment of its military power in Sheila A. Smith's new book, "Japan Rearmed," out now: https://on.cfr.org/2uDyk9Z

-

Japan Rearmed

![]() Japan’s United States–imposed postwar constitution renounced the use of offensive military force, but, Sheila A. Smith shows, a nuclear North Korea and an increasingly assertive China have the Japanese rethinking that commitment—and their reliance on U.S. security.

Japan’s United States–imposed postwar constitution renounced the use of offensive military force, but, Sheila A. Smith shows, a nuclear North Korea and an increasingly assertive China have the Japanese rethinking that commitment—and their reliance on U.S. security. -

Japan Rearmed by Sheila A. SmithSheila A. Smith discusses her new book, Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power.

-

Womenomics Is Flipping the Script on Men in JapanIn addressing legal barriers and challenging entrenched gender stereotypes, Japan is pushing for gender equality in the workplace and growing its economy.

-

See How Much You Know About JapanTest your knowledge of Japan, from its postwar alliances to its territorial disputes.

-

The Hanoi Setback and Tokyo’s North Korea ProblemThe abrupt halt to talks in Hanoi between President Donald J. Trump and North Korean Chairman Kim Jong-un has intensified criticism of the U.S. president’s diplomacy and its U.S. domestic implications. But there are larger regional ripples as well, and the interests of U.S. allies deserve closer scrutiny. While the failure in Hanoi to reach an agreement was a serious setback for Seoul, Japan’s immediate assessment was not terribly critical. The initial media response in Tokyo largely reflected the U.S. reaction: was no deal better than a bad one? The answer was largely yes, and there were the inevitable questions about the diplomatic performance of the Trump administration. The government response was far more measured. Tokyo has always viewed the North Korea problem from a different vantage point. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has consistently advocated that President Trump not give in to relaxing sanctions imposed by the United Nations on North Korea (DPRK) for its nuclear and missile programs. The Japanese government has long worked with others in the United Nations to build a serious sanctions regime, and Abe worked hard to persuade the international community of the importance of unity in this effort. Therefore, the announcement that the United States was not going compromise on sanctions must have been welcome news. Indeed, Abe, after a brief phone call with President Trump on his way home from Hanoi, announced his support for the president’s decision to end discussions over Pyongyang’s request for sanctions relief. Yet there are collateral concerns in Tokyo that will need to be considered in any future U.S.-DPRK negotiations. Three issues will shape Japanese thinking about their diplomacy going forward. First, a negotiated denuclearization seems unlikely in the short term, and this conflicts with Tokyo’s strategic preferences. A bad outcome for Tokyo would be a deal that leaves North Korea’s nuclear weapons capabilities largely in place, or even worse, acknowledges North Korea’s nuclear status. Here we should expect Japan to continue to admonish the United States and others in the most strenuous terms possible the consequences of a bad deal for U.S. extended deterrence in Asia. Second, Japan more than any other regional power must be relieved to no longer be on the receiving end of North Korean missile launches. While there was no indication in the run-up to the Hanoi meeting that the United States and North Korea had agreed to diminish or eradicate Pyongyang’s missile production facilities, the freeze on missile and nuclear testing must be welcome in Tokyo. A moratorium on missile testing was central to Japan’s own diplomacy with Kim Jong-un’s father almost two decades ago, and will likely continue to be should Japan-DPRK talks ever begin. But a moratorium on testing does nothing to diminish Pyongyang's missile arsenal, including not only ICBMs but also medium- and short-range missiles that can threaten Japan. Finally, the most difficult outcome for Prime Minister Abe from the breakdown in Hanoi may not be about Japan’s security but rather about the accountability of the Kim regime on human rights. The fate of the Japanese citizens abducted by Pyongyang remains a highly sensitive issue for political leaders in Tokyo, none more so than Prime Minister Abe. Repeatedly, President Trump and others in his cabinet have publicly committed the United States to advocate on behalf of Japanese citizens in North Korea. And yet, the president’s willingness to absolve Kim of responsibility for the death of Otto Warmbier, the American student detained and brutally beaten while in North Korean custody, must have given Tokyo pause. If the U.S. president is not going to hold Kim responsible for the fate of his own citizens, it is unlikely that he will stand firm on behalf of Japanese. Immediately following the president’s press statement in Hanoi, Prime Minister Abe held a press briefing of his own in which he said that he must now pursue directly Japan’s interests on the abductees with Kim Jong-un. The failure of talks in Hanoi may not be a complete setback for diplomacy. It is too early to tell how this might evolve. U.S. allies will want to ensure that the Trump administration continues to consult as next steps are considered. No one wants a return to the uncertainty and danger of 2017, to be sure. But equally worrisome in the wake of the Hanoi summit is the possibility that President Trump might lose interest in trying to solve the North Korea problem.

-

Japan-South Korea Tensions Spur the Need for Courage and CreativityThis post is co-authored with Brad Glosserman, deputy director of and visiting professor at the Tama University Center for Rule Making Strategies and senior advisor for Pacific Forum. Scott A. Snyder and Brad Glosserman are co-authors of The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash: East Asian Security and the United States. A series of incidents have driven relations between Japan and South Korea to new lows. Frustration has mounted as each government has blamed the other for the sorry state of affairs. Though domestic politics is partially to blame, the real problem is more deeply rooted. Each country sees the other as the cornerstone of its own national identity, and their respective self-images make conflict inevitable. While the U.S. can help the two countries address this problem, only courageous and inventive leadership in Tokyo and Seoul can resolve it. Recent incidents that have roiled the Japan-ROK relationship include: encounters between military aircraft and naval vessels that violate standard operating procedures and indicate hostile intent, such as turning on fire-control radars; ROK court rulings that disregard provisions of the 1965 treaty that normalized relations between the two countries and allow laborers forced to work for Japanese companies during World War II to sue for back pay; the Seoul government’s decision to shut down the foundation established in December 2015 to provide financial support for women forced into sexual servitude during the war (the “comfort women”); the Seoul government’s decision to revisit and ultimately abandon the 2015 agreement between the two governments that purported to “permanently resolve” the issue. Other longstanding issues include: the territorial dispute over islands called Dokdo by South Korea (which occupies the islands), Takeshima by Japan, and the Liancourt Rocks by those who don’t want to take sides; the name of the body of water between the two countries: it is generally recognized as the Sea of Japan, but Koreans want it to be called the East Sea; the suppression of Korean culture and the appropriation of cultural artifacts by the Japanese during their occupation of the peninsula. For most observers, the source of tension between the two countries is the legacy of Japan’s occupation and colonization of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945. Imperial Japan was a brutal occupier and that period’s lasting impact continues to sour relations, despite the 1965 agreement to normalize relations and geopolitical factors—alliances with the U.S., shared values and interests, and common threats (North Korea in particular)—that seemingly ought to force the two countries toward closer relations. The real cause of strained relations, however, lies less in past disputes than in the present and the future—that is, each country’s conception of itself. The Republic of Korea has established its nationhood narrative in opposition to the experience of Japanese colonial rule. The occupation inflicted extraordinary pain on the Korean people and ended with a division between North and South Korea that persists to this day. Despite South Korea’s extraordinary successes—overcoming authoritarian rule, building a vibrant democracy, and creating the world’s 11th largest economy all in the shadow of an existential threat from North Korea—the core of modern South Korean identity is the struggle against Japan. Korea is also central to Japanese national identity, but in a different way. Korea is a direct challenge to the national narrative that Japan is a peaceful nation and was also a victim of World War II. The Korean perception of Japan as a predator that has not rectified the harm it inflicted and cannot be trusted to not repeat that history clearly contradicts the post-war Japanese self-image as a peaceful state, and belief that in 1945 there was a profound break with the past. Both national identities cannot be true at the same time, and therein lies the problem: the assertion of one identity undercuts the legitimacy of the other. Fortunately, national narratives are constructed. They are built by elites through storytelling and the writing of national histories and the symbols and ceremonies are used by contemporary governments to build and sustain support of their publics. In a nation-first era, both governments intentionally emphasize the discord in their relationship rather than the positive elements. But leaders in Seoul and Tokyo can overcome this narrative with courage and imagination. They can adopt a different perspective that emphasizes common values and concerns. A more long-term outlook would acknowledge the difficulties the two countries face and affirm that they will be better able to surmount these challenges by working together, rather than by using the other as a foil or scapegoat. The U.S. can help this process along and, in the past, Washington has been instrumental in facilitating better relations between its allies. This problem requires attention from the highest levels of the U.S. government, and so far that effort has not been forthcoming. That is a mistake. The U.S. should do more not only to align its allies as they attempt to deal with critical security concerns, but also to help lay the foundation for a stable and genuinely cooperative trilateral relationship. This post originally appeared on Forbes.

-

Japan's Active DefensesThe Abe cabinet announced its new ten-year defense plan this week, promising to spend 27 trillion yen ($240 billion) over the next five years on Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF). Eye-catching in the announcement was the decision to refit the Maritime Self-Defense Force’s biggest destroyer, the JS Izumo, to allow fighter jets to operate off its flight deck, an unabashed upgrade to aircraft carrier. But the import of the 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) is far greater: Japan is deeply worried about the military balance in Northeast Asia and is doing it all it can to make sure its military is ready for conflict and to ensure the United States remains committed to its security. The 2018 NDPG looks ahead over the next ten years to anticipate Japan’s defense needs, noting the “accelerating pace and deepening complexity of the global power balance” as the most unnerving factor in Tokyo’s defense planning. Regional threat perception matters most, however, and Japan’s highest concern continues to be the expanding military powers of China and North Korea. China’s expanding maritime and air capabilities offer significant challenges to Japan’s SDF, and the NDPG points out that the “massive and rapid reclamation in the South China Sea” creates “a military flash point “ where China continues its intensive air and maritime operations. The NDPG also notes North Korea’s vastly improved ballistic missile capabilities that, coupled with its WMD stocks, offer the most immediate concern for Japanese planners. In Tokyo, the import of recent North Korean launches is that Pyongyang can now launch missiles simultaneously and with the capacity for surprise. Perhaps most striking, however, was its conclusion about recent negotiations with Kim Jong-un: “there has been no fundamental change in North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities.” Moreover, cyber and information warfare capabilities in Pyongyang seem to be increasing, offering a threat to Japan, to others in Asia, and to the world. Also striking was the inclusion of Russia in Japan’s defense concerns. Despite Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s efforts to negotiate a peace treaty with President Vladimir Putin, the NDPG takes note of Russia’s efforts to modernize its military forces and particularly its strategic nuclear forces. The NDPG notes Russian military activities are not only growing in the Arctic, Europe, the vicinity of the United States, and the Middle East, but are also increasing in the Far Eastern region, including around the Northern Territories. The 2019–2023 procurement plan that accompanies this new defense plan includes an array of new capabilities for the Self-Defense Forces, with a 3 trillion yen ($26.9 billion) boost from MOD’s last five year plan. Yet this still may not be enough to keep pace with the rapidly growing capabilities of Japan’s neighbors. For example, China reports spending around $151 billion in 2017 on its defenses, although the actual figure may be higher. In contrast, Japan is planning to spend on average just under $50 billion annually over the next five years. Nonetheless, the new capabilities that Japan’s defense planners seek to integrate into their military are significant. The NDPG highlights the need for “multi domain” operations, and while Japan already has one of the world’s most competent maritime forces, it must now enhance its ability to operate in cyber and space. A new space operations command will be established, with up to 500 personnel. And all three services will be required to have a dedicated cyber unit as well as capabilities to cope with the use of electromagnetic pulses designed to disable Japanese communications and information systems. Japan’s vulnerability to missile attack is real. While North Korea’s arsenal is singled out in the NDPG, all of Japan’s neighbors have ballistic missiles and (almost) all are nuclear powers. Despite enhancing its ballistic missile defense (BMD) capabilities, Tokyo will have little serious ability to strike back if it is attacked. North Korea, Chinese, and Russian forces continue to demonstrate their ability to challenge Japan’s airspace and to launch significant offensive operations against Japan. For years now, Japan’s air and maritime forces have remained on constant alert, aiming for a 24/7 operational readiness. The focus on Japan’s ability to counter an attack is perhaps the most striking feature of the 2018 defense plan. Both the NDPG and the five-year procurement plan highlight the importance of readiness and resilience. But this NDPG focuses attention on Japan’s overall air defenses, introducing both enhanced missile detection and destruction capabilities as well as accelerating the modernization of Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) fighters. The land-based AEGIS Ashore system will be introduced over the coming years, to be fully operational by 2023, giving Japan far greater ability to detect, target, and if necessary, destroy incoming ballistic missiles. Integrating land, sea, and air based BMD systems will be a priority once this new system is deployed. The Ground Self-Defense Force will manage this new land based capability, and the command and control system for Japan’s integrated ballistic missile defense system—including the Maritime Self-Defense Force’s (MSDF) ship-based AEGIS and the Air Self-Defense Force’s PAC-3s—will need to be updated. Japan’s air force gets a significant upgrade over the next decade. The introduction of the F-35A fighter has been in the works for several years now, with 42 new fighters (or two squadrons) planned for deployment by 2021. Japanese pilots are already training on the F-35A, and by 2021, these new fighters will replace the aged F-4 Phantoms. But the scope of the modernization plan announced this week is much greater. Japan will now purchase a total of 147 F-35s, adding 105 more to those already on their way to Japan. Of these, 42 will be the F-35B, capable of short takeoff and vertical landing, and the additional F-35As will replace the early model F-15s in use now. The pace of deployment will depend largely on how fast they can be built. The addition of short takeoff and vertical landing F-35Bs to the arsenal offers the ASDF more options as it considers its southwestern defenses. This fighter can operate off of short runways, including a refitted flight deck on the MSDF’s largest helicopter destroyers. The JS Izumo is smaller than the newest U.S. carriers (27,000 v. 100,000 ton displacement); and perhaps more to the point, smaller than estimates of China’s newer carriers (66-70,000 ton displacement) destined for the East and South China Seas. According to the Ministry of Defense, the new F-35Bs will not be permanently stationed aboard MSDF ships, but Tokyo clearly is increasing its options and thinking aloud about how a conflict in its southwestern region might evolve. Important to that scenario are standoff missiles that will give the SDF greater capacity to confront any aggression offshore. These missiles (the JSM, the JASSM, and the LRASM) are all air-based and long-range, with ranges estimated from 500 to 1,000 kilometers. Moreover, new anti-ship missiles and hypersonic guided missiles are under development for the SDF’s island defense mission. Japan’s SDF will now have more muscular weapons and the capacity to detect foreign military activities—and potentially respond to threat—far more quickly. New capabilities in cyber and space will be built, and new command and control structures will be refined to accommodate these emerging capabilities. Recognizing the need to take action in case of new threats from cyber, space, and via electromagnetic pulse, the SDF will be driven to develop a more integrated defense posture. Beyond that, the three services will need to coordinate their new capabilities in combined operations with the United States. Clearly, President Donald J. Trump’s public request of Prime Minister Abe last year to buy more advanced U.S. weapons systems had some influence on Japanese decision-making. But there are some important trade-offs being made as a result. The F-35s will be purchased off the shelf from the United States, and the co-production arrangement that allowed Japanese manufacturers to produce in Japan will end. But there is another fighter still under consideration in Tokyo, a new fighter to replace the multi-role F-2. Once again, Japanese planners are considering their industrial capacity and acquiring the technology and experience in building a fighter remains a longer-term aim. For now, the Japanese government has clarified its intention to organize a Japanese-led consortium to build the F-2 replacement. Tokyo’s defensive military doctrine is under increasing pressure from the far more sophisticated and assertive military forces that operate in and around Japanese territory. This is amply evident in the 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines. Yet, as I argue in my forthcoming book, Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power, the growing military pressure from Japan’s neighbors is only one part of the equation. Changing U.S. views on its alliance commitments, as well as a growing confidence within Japan over its use of military power, all factor into Tokyo’s strategic thinking.

-

The Quad and the Free and Open Indo-PacificOver the weekend the Halifax International Security Forum convened its tenth iteration, one that observed the hundredth anniversary of the 1918 armistice ending World War I, and took the occasion of the forum’s own anniversary to reflect on the deliberations of the past decade. One of the distinguishing features of the Halifax forum lies in its selection of participating countries: only democracies are invited. An all-democracy forum on security raises the visibility of values issues—in the forum’s own words, “a security conference of democratic states that seeks to strengthen democracy.” This year’s plenary deliberations included more attention to Asia and the Indo-Pacific region than in the past—and surfaced concerns about China, trade, the Belt and Road Initiative, technology, and surveillance. The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command commander, Admiral Phil Davidson, provided a keynote that reinforced the speech Vice President Mike Pence had delivered away in Port Moresby just hours earlier at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum summit. Davidson, given his specific focus on Indo-Pacific security, offered more expansive detail about what the administration means when it refers to a “free and open” region: “free from coercion by other nations” as well as free “in terms of values and belief systems” “individual rights and liberties” including religious freedom and good governance “the shared values of the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” “all nations should enjoy unfettered access to the seas and airways upon which our nations and economies depend” “open investment environments, transparent agreements between nations, protection of intellectual property rights, fair and reciprocal trade” Davidson took care to echo Vice President Pence’s invitation to China to participate in a free and open Indo-Pacific, as long as Beijing “chooses to respect its neighbors’ sovereignty, embrace free, fair, and reciprocal trade, and uphold human rights and freedom.” The session titled “Asia Values: A Free and Open Indo-Pacific” featured speakers from all four of the “Quad” countries: Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. One panelist noted the divergent geographic definitions of the Indo-Pacific: a common map for India, Japan, and Australia—one that ends on the east coast of Africa—but a U.S. view that ends with India’s west coast, leaving out the huge expanse of the Indian Ocean. (More on the geographic gap, with maps, from my perspective here.) Any number of other countries could have been represented, but by framing the discussion through the prism of the Quad, the session got to topics such as the Quad’s own evolution of purpose. What began as a humanitarian coordination effort among the four countries with the December 26, 2004 tsunami had a brief life as a “Quadrilateral Security Dialogue” meeting in 2007. But Australia later removed itself from that framework, and the four did not meet again until 2017. Since 2017, the Quad has met formally—at the assistant-secretary level—three times, the most recent of which took place in Singapore on November 15. These meetings, however, are no longer referred to as a “Quadrilateral Security Dialogue” but by the more anodyne “U.S.-Australia-India-Japan Consultations” (or other variants according to the capital issuing the statement: Canberra, New Delhi, or Tokyo). As the Halifax discussion on the Indo-Pacific highlighted, the Quad framework has evolved to take up matters not solely in the military-security lane. The conversation usefully raised ideas for the four countries to pursue together, such as increased cooperation for “instruments to meet the infrastructure demand” (some is already underway, but the need is great), counterproliferation and counterterrorism cooperation, and continued work to build greater interoperability among all four countries in order to better respond to humanitarian emergencies. Reflecting on the powerful symbol of all four democracies, and what they could do together, I was struck by the divergence in the otherwise similar statements released by each country following the November 15 Quad meeting in Singapore. Australia, Japan, and the United States all made reference to “exchang[ing] views on regional developments including in Sri Lanka and Maldives.” India, however, just noted “recent developments in the regional situation.” Challenges to democracy in Sri Lanka and Maldives suggest exactly the type of regional developments that all four Quad members ought to be able to discuss freely and openly, and consider what support they might be able to offer. As we look ahead to more consultations among the Quad, all of us interested in the potential of this framework should be thinking about what it means for four democracies to develop a common agenda for the region. At a time of technological change, and new realizations about the vulnerabilities of all of our democracies—the precise vulnerabilities of open societies—perhaps the Quad democracies should be looking ahead to over-the-horizon issues that will be central to strengthening not only our own democracies but also others in the region. My book about India’s rise on the world stage, Our Time Has Come: How India Is Making Its Place in the World, was published by Oxford University Press in January. Follow me on Twitter: @AyresAlyssa. Or like me on Facebook (fb.me/ayresalyssa) or Instagram (instagr.am/ayresalyssa).

-

A Missed Opportunity to Commemorate a Positive Moment in Korea-Japan RelationsScott Snyder and Brad Glosserman are co-authors of The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash: East Asian Security and the United States. Anniversaries loom large in international relations. They are opportunities to shape historical narratives. This is especially so in relations between Japan and South Korea, where anniversaries commemorating dark moments in history abound. It is particularly disappointing when opportunities are missed to commemorate positive developments, such as the 20th anniversary of the Obuchi-Kim summit that held out the prospect of a new partnership between Japan and South Korea. Indeed, the 20th anniversary of the Obuchi-Kim summit may have been overlooked precisely because it was a sobering reminder of missed opportunities and the fraught nature of the Japan-South Korea relationship, one that despite great promise remains a captive of the past. It is an equally powerful symbol of the peril of focusing on history rather than the future. Twenty years ago in October, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung and Japanese Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo stunned the world by agreeing to build “a new Japan-Republic of Korea partnership toward the twenty-first century.” The foundation of this new relationship was Japan’s readiness to “squarely face the past,” which Obuchi acknowledged with “a spirit of humility, the fact of history that Japan caused … tremendous damage and suffering to the people of the Republic of Korea through its colonial rule.” In return – and every bit as important as Japan’s recognition of its historical misdeeds – Kim “accepted with sincerity” the prime minister’s statement and “expressed his view that the present calls upon both countries to overcome their unfortunate history and to build a future-oriented relationship based on reconciliation as well as good-neighborly and friendly cooperation.” The two men recognized the convergence of their respective national interests and their desire to work together to build a mutually beneficial future. They pledged to cooperate on issues of national security and economics, and to promote personnel and cultural exchanges, especially among the young generation. Their joint declaration was an extraordinary document, a blueprint that if followed would transform East Asian political dynamics. Unfortunately, its ambitions proved too great and politicians in both countries proved unable to resist the siren song of nationalism when domestic politics provided an opportunity to play the history card. As a result, this October, rather than celebrating the 20th anniversary of the joint declaration, the two countries were contemplating the incipient collapse of the December 2015 Comfort Women Agreement, a deal struck by the government of President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. The agreement survived formal review by the administration of President Moon Jae-in, which inherited it after Park was impeached. Even though Moon called it “seriously flawed,” his government conceded that the deal had been agreed upon by both countries and therefore would not demand renegotiation. Seoul continued to pick at the arrangement, however, and decided to unilaterally dismantle the Japanese-funded foundation it created to provide support to comfort women and their families; that funding stream would be replaced by Korean resources. This decision reflected no small irony. Korea had for many years rejected the Asian Women's Fund – the nongovernment mechanism set up by Tokyo in the 1990s to provide compensation to the comfort women – as an unacceptable proxy for an admission of responsibility by the Japanese government precisely because it did not provide direct funding to redress the harms done to the comfort women. The deal is also threatened by the comfort woman statues erected by nonprofit groups in Busan in front of the Japanese consulate there, in addition to the comfort women statue that stands in front of the site of the Japanese embassy in Seoul. Under the December 2015 agreement, Seoul said it “will strive to solve this issue in an appropriate manner through taking measures such as consulting with related organizations about possible ways of addressing this issue.” But the Moon administration has allowed nongovernmental activists to take actions that have instead intensified the standoff. A South Korean court ruling earlier this week that the 1965 Japan-Republic of Korea normalization treaty does not protect Japanese firms from claims by individuals for compensation for forced labor will further complicate the Japan-South Korea relationship. Such actions reject the “future-oriented perspective” of the Kim-Obuchi agreement signed two decades ago (and the December 2015 Comfort Women Agreement) and reinforce domestic influences over the Japan-Korea relationship that paralyze its progress. Moon and Abe should instead work to free the relationship from domestic politics through a fundamental transformation of political dynamics between the two nations. One way of doing so is laid out in our 2015 book, The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash, where we proposed a "go bold" strategy by which Japanese and South Korean leaders would embrace statesmanship by addressing core issues in the relationship, building on the spirit of the Kim-Obuchi declaration. Our recommendations included the establishment of a joint holiday to mark Japan-South Korea reconciliation, effective efforts to bring finality to the comfort woman issue, and Japan's abandonment of its claim to Korean-controlled islands that South Koreans view as reminders of Japanese imperialism. Those efforts would help transform the bilateral relationship and allow both countries to jointly address shared security concerns through cooperation based on common values. Achieving this goal, however, is only possible if both leaderships return to the approach embodied in the Kim-Obuchi declaration. The question, more potent than ever in an age of competing nationalisms, is whether Moon and Abe can muster the political will to swim against the tide in pursuit of an outcome that would materially benefit the national interests and bring a measure of finality to the historical demons that have beset both sides. Such efforts will become even more important in light of intensifying security challenges both countries will likely face in the future.

-

Moon Jae-in’s 2018 Liberation Day Speech and South Korea’s Foreign PolicyThe commemoration marking the anniversary of the end of World War II is always a bittersweet moment in South Korea. It marks a day of euphoria on the Korean peninsula that carries with it both the legacy of the past and the burdens of the future. As Korean War historian Sheila Miyoshi Jager observes, “Korea was not liberated by Koreans, and so Korea was subjugated to the will and wishes of its liberators.” Moon Jae-in’s speech marking the seventy-third anniversary of the end of World War II is particularly fascinating in its bold effort to challenge that assertion. This can be seen both through Moon’s efforts to redefine South Korea’s fraught diplomatic relationship with Japan and for the insight the speech provides into Moon’s audacious and potentially risky effort to redefine inter-Korean relations and reshape the geopolitical landscape in Northeast Asia. Moon’s efforts to come to terms with Korea-Japan relations are particularly conflicted. Moon begins his speech by asserting that “The history of pro-Japanese collaborators was never a part of our mainstream history.” Instead, Moon defines a liberation narrative that celebrates South Korean agency by drawing on South Korea’s impressive post-war accomplishments as the only former colony to “succeed in achieving both economic growth and democratic progress.” But the examples Moon uses in his speech to demonstrate Korea’s desire for liberation in his speech all involve resistance to Japanese colonial rule. In addition, Moon’s rejection of the terms of the December 2015 comfort woman agreement made by his predecessor led the Moon administration to establish August 14 as a new holiday, Comfort Women Memorial Day, and to launch a new think tank devoted to comfort woman research, the Women’s Human Rights Institute of Korea. Moon stated his Comfort Women Memorial Day address his view that the comfort woman issue cannot be solved diplomatically, but rather should be addressed through global consciousness-raising about sexual violence against all women. Unfortunately, Moon’s message was badly undercut domestically since it coincided with the South Korean judicial acquittal of former South Chungcheong provincial governor Ahn Hee-jung on charges of raping his secretary. Rather than helping to marginalize Japan’s historical legacy as part of Korea’s liberation narrative (and thus reducing its salience as a diplomatic stumbling block), the steps Moon has taken thus far appear more likely to perpetuate it, just as Japan’s establishment of Takeshima Day (to mark Japan’s claim to the island that South Korea effectively occupies and refers to as Dokdo) strained Korea-Japan relations over a decade ago during the administration of Roh Moo-hyun in which Moon previously served. These developments have contributed to a hardening of public opinion over the comfort woman issue within the past year in both Japan and South Korea, as shown in the 2018 annual Genron NPO-East Asia Institute (EAI) Joint Poll on Japan-Korea relations and other polls. (Interestingly, the Genron-EAI shows that a plurality of Japanese and a majority of South Koreans support strengthened trilateral security cooperation among the United States, Japan, and South Korea.) Under Moon and Abe, Japan-South Korea relations appear cordial, but fragile. The centerpiece of Moon’s speech on the future of the inter-Korean relationship turns on the phrase “taking responsibility for our fate ourselves” as a way to overcome historic divisions that have hobbled Korea’s autonomy. Moon outlines his administration’s efforts to win international support for his efforts to promote regional peace and prosperity, including agreement with President Donald Trump to “resolve the North Korean nuclear issue in a peaceful manner.” Looking forward to a third inter-Korean summit in Pyongyang, Moon declares the objective of the meeting as “an audacious step to proceed toward the declaration of an end to the Korean War and the signing of a peace treaty as well as the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.” Moon then presents a bipartisan vision of Korean peninsula-centered Northeast Asian economic integration, beginning with his proposal to establish an East Asian Railroad Community. This is a concept that has been endorsed under various names by every South Korean president since Kim Dae Jung. It is evocative of the same elements contained in the Eurasian Initiative and Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative (NAPCI) launched by Moon’s discredited predecessor, Park Geun-hye. The key to unlocking a new way forward, according to Moon, is Korean leadership as “the protagonists in Korean peninsula-related issues. Developments in inter-Korean relations are not the by-effects of progress in the relationship between the North and the United States. Rather, advancement in inter-Korean relations is the driving force behind denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” It is a bold approach that places South Korea at the crossroads of Northeast Asia and crystallizes Moon Jae-in’s efforts to manage the conflict between South Korea’s desire for autonomy and its need for alliance. The coming weeks and months will test whether Kim Jong Un—and President Trump—accept Moon’s proposition that a Korean peace will catalyze regional and global stability.

-

Is South Korea Pro-China and Anti-Japan? It’s Complicated.Sungtae (Jacky) Park is a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations. The history of Korea’s relations with China and Japan going back to ancient times shows that Koreans have always had a complicated, yet pragmatic relationship with their neighbors, and recent South Korean public opinion polls on China and Japan, too, have been fluctuating depending on circumstances. Current social and geopolitical trends also seem to forecast improvement in Japan-South Korea relations and deterioration in China-South Korea relations. Miscalculating South Korea’s geopolitical orientation could lead to lesser support on the part of Americans for the U.S.-South Korea alliance, less solidarity on the part of Japanese with their South Korean quasi-allies, and further emboldening on the part of Chinese in the attempt to pry South Korea away from the United States. As the Korean Peninsula has historically been the center of geopolitical competition in Northeast Asia, a nuanced understanding of Seoul’s position and perception toward Beijing and Tokyo would help all relevant parties contribute to long-term strategic stability in the region. Read more on The National Interest.

Online Store

Online Store