Perilous Pathogens: How Climate Change Is Increasing the Threat of Diseases

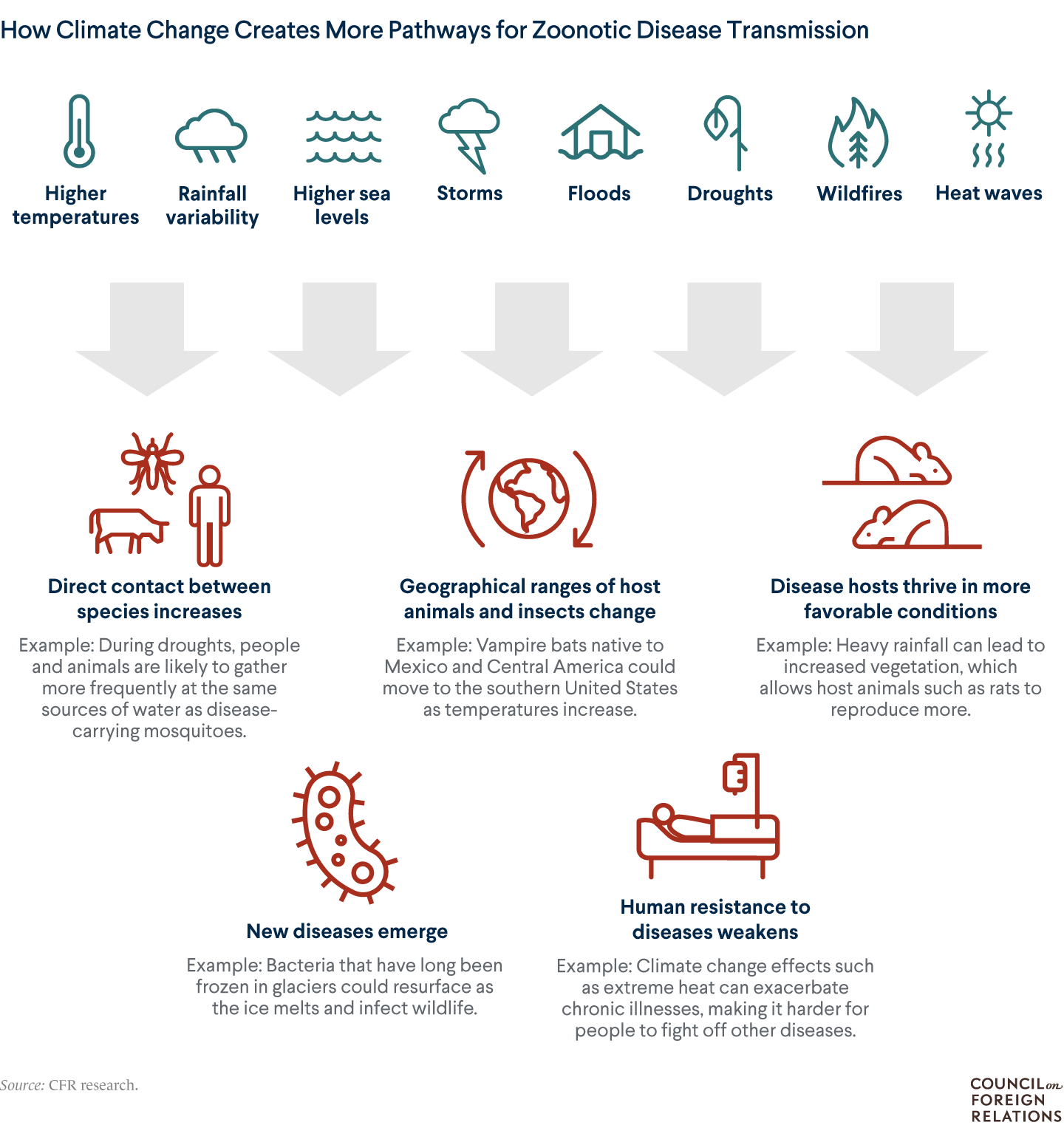

Climate change is creating many pathways for zoonotic diseases to reach people. Four cases show how the climate crisis is altering disease threats and how the world can respond.

November 4, 2022 4:12 pm (EST)

- Article

- Current political and economic issues succinctly explained.

The world is already witnessing the consequences of human-caused climate change, including hotter temperatures, rising sea levels, and more frequent and severe storms. What’s harder to see are climate change’s effects on the spread of disease: on the mosquito that carries a virus, or the pathogenic bacteria on a piece of fruit.

A growing body of studies shows the link between climate change and the increasing threat of zoonotic diseases, or those transmitted from animals to humans.

More on:

In Southeast Asia, cases of dengue fever have soared as longer rainy seasons and more frequent and severe floods allow mosquitoes to thrive. Warming temperatures in North America are expanding the range of ticks that carry Lyme disease. They’re also providing better conditions for bats and other suspected hosts of Ebola in Central Africa. And in South America, there are concerns that increased variability in rainfall could drive more cases of rodent-borne hantavirus diseases.

But experts say the world is not prepared for climate-driven outbreaks. And like with other consequences of climate change, poor countries will suffer much more. Preventing the next global health emergency is possible, though, if governments and international institutions step up.

Dengue Fever in Southeast Asia

What is it?

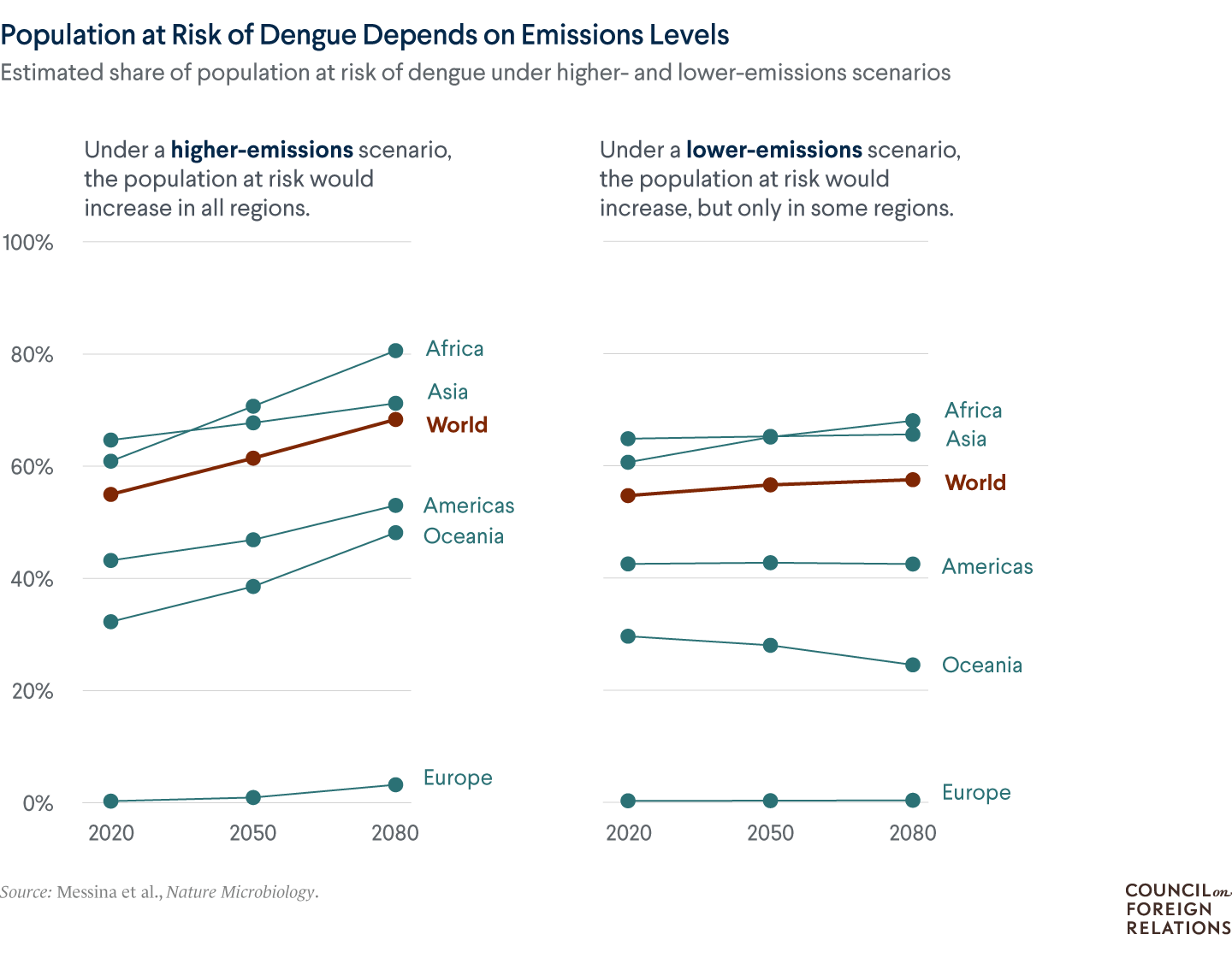

Dengue is a viral infection endemic in many tropical regions, meaning its presence is steady or predictable there. It has been reported in 129 countries, and about half of the world’s population—nearly four billion people—lives in areas where there is a risk of contracting the disease. Every year, between one hundred million and four hundred million cases are reported worldwide, 70 percent of which are in Asia. Dengue spreads when infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes bite people. Most cases are mild, with symptoms including fever and headache, and it rarely kills people.

What’s the link to climate change?

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes thrive in warm, wet environments. As temperatures rise, the insects can survive in areas that were previously too cool for them. Warmer temperatures also shorten the time it takes for young mosquitoes to become disease-spreading adults. In addition, the mosquitoes usually lay their eggs in standing water, so floods can lead to increased dengue cases as the mosquito population grows. For example, after Typhoon Rai struck the Philippines in 2021, several areas suffered increased cases. Cases can also increase during droughts because people are more likely to store water in containers, where the mosquitoes prefer to lay their eggs.

More on:

How’s the threat changing?

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that an additional two billion people [PDF] worldwide could be at risk of contracting dengue if the world’s average temperature continues to rise. In Southeast Asia, dengue fever outbreaks aren’t new, but in recent years, cases have increased dramatically, in part due to longer rainy seasons. At the same time, areas where dengue wasn’t previously endemic have suffered outbreaks. In Brazil—which reported nearly two million cases in 2022 as of August, the most in the world—the disease has spread to higher altitudes. And in Japan, which in 2014 suffered its first dengue outbreak in seventy years, researchers warn that the country could suffer more outbreaks with climate change.

How do countries manage it now?

Countries where dengue is endemic rely on mosquito control. In addition to spraying insecticides, governments are increasingly using lab-bred male mosquitoes that carry Wolbachia bacteria. When these mosquitoes mate with females, their eggs don’t hatch.

After a successful trial in Vietnam, several Southeast Asian countries are implementing a system known as D-MOSS, which analyzes satellite data and climate forecasts to predict the likelihood of dengue outbreaks up to seven months in advance.

Public health departments also encourage people to use mosquito nets, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants to prevent bites, and avoid keeping open containers of water near the home. The world’s first dengue vaccine was licensed in 2015, and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends its usage only as part of a broader prevention strategy. Despite the global threat it poses, there is little international collaboration on tackling the disease.

Lyme Disease in North America

What is it?

Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia bacteria, affects large parts of Asia, Europe, and North America. People can be infected through bites from black-legged ticks, which also feed on small mammals and birds. Lyme can cause fever, headache, fatigue, joint and muscle pain, and a skin rash that resembles a bull’s-eye, among other symptoms.

Lyme can be hard to diagnose, though, because not everyone gets the hallmark skin rash, and it can take weeks for the body to create enough antibodies for a diagnostic test to detect. Most cases of Lyme can be successfully treated with antibiotics, but some patients suffer persistent symptoms for months or years.

What’s the link to climate change?

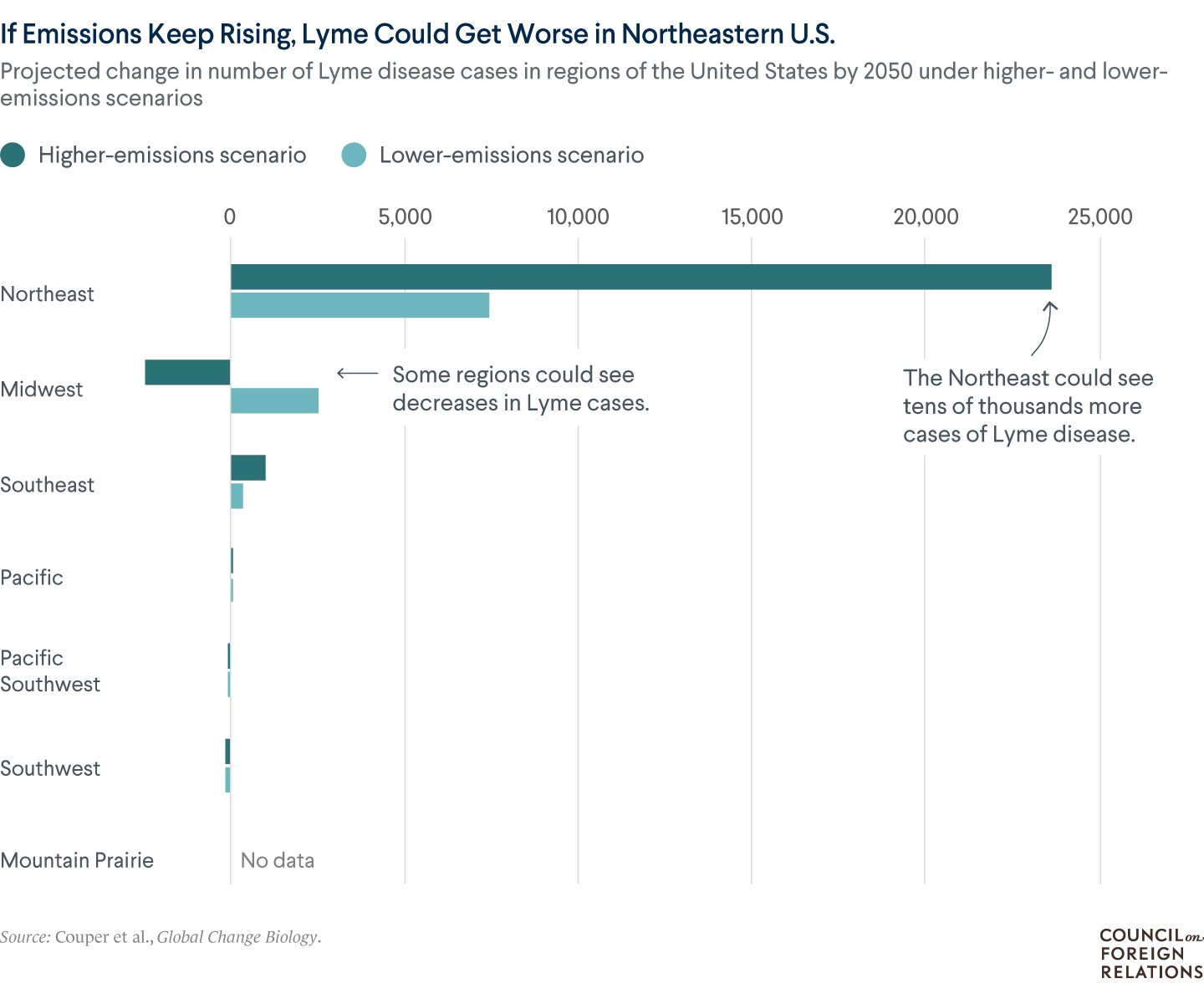

Warming helps to expand the disease’s geographic range. Ticks thrive in temperatures above 45°F (7.2°C) and in more humid climates, so warming across North America offers more friendly habitats for the arachnids. Like with mosquitoes, a hotter climate can speed up the time it takes for a young tick to become an adult, consequently shortening the overall reproductive cycle. Also, more mild winters allow some ticks to survive through the cold season and stay active for a longer time period each year. Climate change can affect other environmental factors, too, such as population levels of deer and other hosts.

How’s the threat changing?

As the world’s average temperature has risen, the number of new U.S. Lyme cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has nearly doubled since the early 1990s, to around thirty thousand each year. (The CDC notes that the actual caseload is likely greater, and U.S. insurance estimates put the number of people diagnosed and treated for Lyme each year at around 475,000.) Northeastern and upper midwestern U.S. states have experienced the sharpest increases, and cases are projected to climb further as greenhouse gas emissions continue to go up. In Canada, the caseload has jumped from the hundreds to the thousands in recent years.

How do countries manage it now?

Treatment of persistent Lyme symptoms can be expensive; a 2015 study found that it costs the U.S. health-care system up to $1.3 billion per year. So, the United States has focused heavily on raising public awareness of preventive measures and early Lyme symptoms. The CDC distributes educational materials, including signs with information about preventing tick bites posted along thousands of outdoor trails.

Canada’s public health agency has likewise focused on awareness campaigns, particularly among outdoor workers, and researchers are experimenting with more cost-effective ways to inform the public. Still, many scientists say there are wide gaps in their understanding of the disease, and research and development of new treatments have historically been underfunded.

Ebola in Central Africa

What is it?

Ebola is a relatively rare but severe infectious disease mainly found in Central Africa. It is thought to be transmitted to humans by animals including fruit bats, primates, and porcupines. Transmission between people can then happen through direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected person. The virus attacks the immune system, with typical symptoms including fever, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and internal and external bleeding. Roughly half of all cases are fatal; of the forty-six known cases in 2021, there were twenty-seven deaths.

What’s the link to climate change?

Many effects of climate change are expected to provide better conditions for the animals that carry the disease. For example, a warmer and wetter climate in the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) could yield more vegetation to feed more host animals. That creates more opportunities for the virus to jump to humans. Previous outbreaks of Ebola have coincided with shifts from dry seasons to periods of heavy rainfall.

At the same time, people in areas experiencing more frequent droughts could become food-insecure. This could push them deeper into forested areas in search of bushmeat (raw or minimally processed meat from animals such as bats and monkeys) and other food, putting them at greater risk of coming into contact with the virus.

How’s the threat changing?

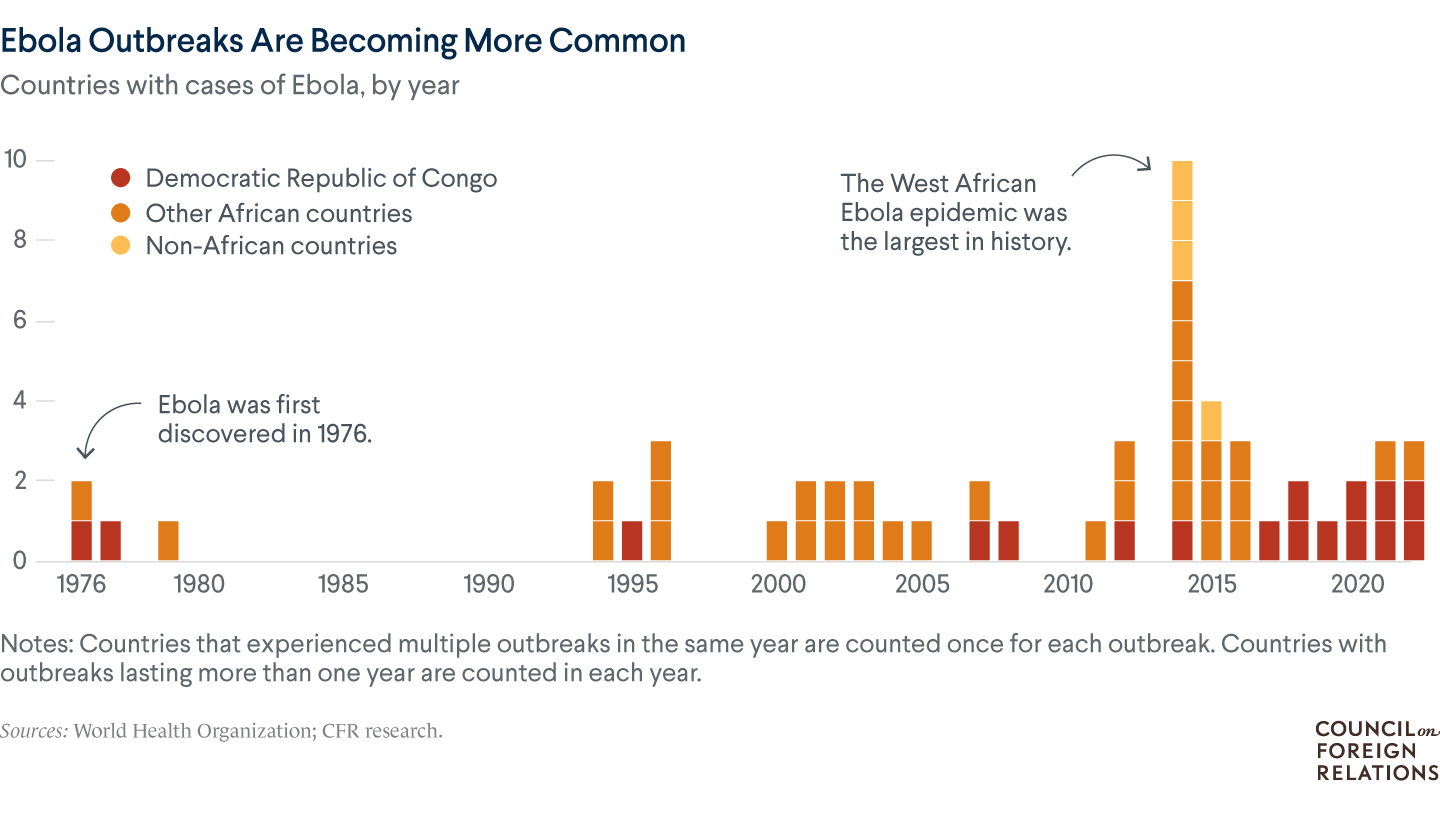

Since the disease was first identified in the 1970s, outbreaks have become more common, in part due to the region’s booming population and urbanization, scientists say. A 2019 study by British and U.S. researchers projected that outbreaks will continue to grow more frequent as temperatures rise and rainfall becomes more irregular: it estimated that by 2070, there will be a several-fold increase in the rate at which the virus spills over to people in Africa. Still, scientific data on the spillover of Ebola to humans is limited, given the challenges of pinpointing the point of contact between an animal host and a person.

How do countries manage it now?

The WHO and national governments undertook major crisis-response reforms following a historic, widespread epidemic in West Africa in 2014–16. Since then, health experts have shortened the time it takes to turn around diagnostic tests; expanded the use of therapeutic treatments; and introduced new vaccines against Ebola. Also, health agencies have depended more on local workers to help build community trust in vaccines and response measures.

However, mistrust and disinformation continues to challenge these efforts, and the tools at African countries’ disposal are largely for emergency response rather than prevention. Vaccination campaigns currently only target close contacts of Ebola patients, and the vaccines only target individual strains. (An ongoing outbreak in Uganda in late 2022 was caused by an Ebola strain that’s resistant to licensed vaccines.) Health systems across the region remain frail, and the COVID-19 pandemic has further weakened their capacity to curb outbreaks.

Hantavirus Diseases in South America

What is it?

Hantaviruses are a family of viruses typically spread by rodents. People can become infected through contact with aerosols from an infected rodent’s saliva, urine, or droppings. Hantaviruses are found in many countries; Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, estimates that approximately two hundred thousand cases of hantavirus diseases are reported globally every year, while another study put the annual total at around one million.

Hantaviruses found in the Americas can cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), an often fatal respiratory disease, while those found in Asia and Europe can cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), which kills at a lower rate than HPS.

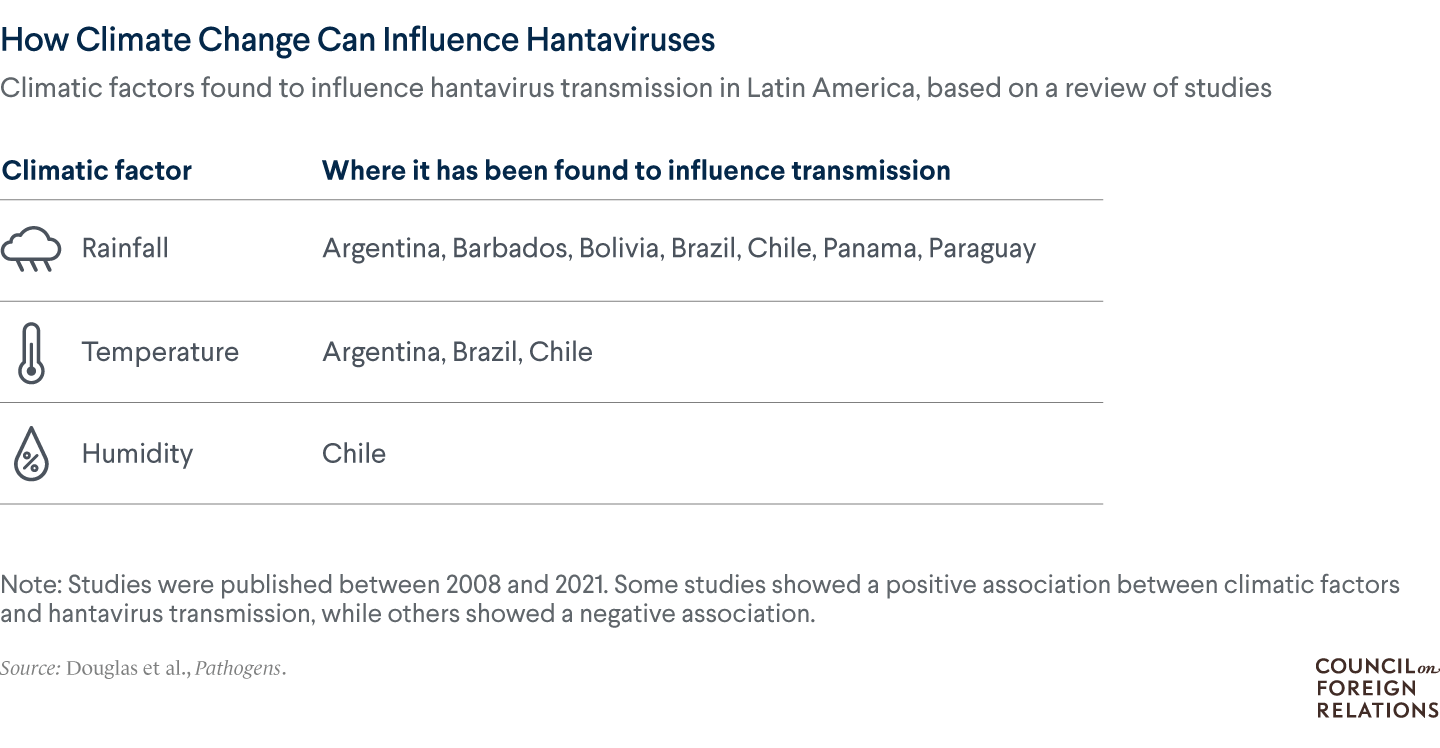

What’s the link to climate change?

Several studies have linked the risk of hantavirus diseases to environmental factors. Some have found that increased rainfall helps boost rodent populations and leads to more cases, similar to what researchers have found for Ebola. Droughts can also increase cases by forcing rodents to seek food in human habitats. Other studies have shown that higher temperatures could lead to more cases. In Brazil, researchers found that predicted temperature rise caused by emissions could increase the number of people at risk of HPS in the city of São Paulo by 30 percent.

How’s the threat changing?

There is limited research on whether global cases of hantavirus diseases will rise due to climate change, but country-specific studies suggest that could be the case. Health officials currently believe that the threat of hantaviruses sparking a pandemic is low, but several developments have generated concerns. In recent years, there has been increased person-to-person transmission of the Andes hantavirus, found in Argentina and Chile. HFRS also has a lengthy incubation period, with symptoms often appearing at least two weeks after exposure, which makes the disease harder to trace. Scientists have urged more research to pinpoint where outbreaks could occur as the world’s average temperature rises.

How do countries manage it now?

Several countries in Central and South America have boosted case surveillance and contact tracing in response to HPS cases in recent years. They’ve also launched public awareness campaigns encouraging people to avoid contact with rodents and spaces that could be infested with rodents, though this can pose a challenge in rural and poor communities. Rodent control, such as trapping, is critical to preventing the spread, as is proper waste disposal. There are no licensed vaccines for hantaviruses, though several are in development.

How Countries Can Prevent and Prepare

As the earth continues to warm, people around the world will see more extreme weather events and greater variability in rainfall and temperature. This could alter the threat of hundreds of known diseases beyond these four examples. “It would be hard to deny that climate change is making the burden of infectious disease worse,” says Brown University’s Rachel Baker. “But the picture of how this looks in ten, twenty, thirty years is uncertain.”

Public health and climate experts agree that governments should take immediate steps to cut off these pathways for disease transmission and save lives. Here are some of the actions they suggest:

Increase research and surveillance.

Scientists say there is still much research to be done to understand the links between climate change and diseases. “One of main challenges in outbreaks is getting dependable data to make quick and effective decisions,” says Kirk Douglas of the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus.

Investing in stronger surveillance and data collection would allow researchers to recognize emerging diseases, better predict future hot spots, and illuminate which pathogens pose the biggest risks. With more information, officials would know where to focus their prevention and preparedness efforts.

Develop vaccines and treatments.

Vaccines are among the best tools for pandemic prevention and control, but their development is a complicated and costly process and global production capacity is limited. The COVID-19 pandemic marked a scientific milestone with the accelerated development of safe and effective vaccines. It also focused attention on stark vaccine inequity and brought to the fore debates over strategies such as waiving patents to expand vaccine access across low- and middle-income countries.

Health experts call for deepening research and development of vaccines against expanding and emerging zoonotic diseases, particularly of universal vaccines, which offer protection from all viruses in a particular family. For example, a universal vaccine for coronaviruses would provide protection against COVID-19, its variants, and all other animal-derived coronaviruses. At the same time, to help combat misinformation and skepticism around vaccines, officials should expand public education and vaccination campaigns, especially in historically marginalized communities.

Move toward health equity.

Climate change affects countries unequally, with many of the lower-income countries that contributed least to the crisis suffering the worst effects. Multilateral and nonprofit organizations have worked to secure funding for low-income countries to boost their health-care systems, as well as provide vaccines and training. And high-income countries have committed to providing billions of dollars to help countries reduce emissions and adapt to climate change. But so far, financing has fallen short of their commitments. In 2021, about 70 percent of countries said their biggest obstacle to implementing national climate and health plans is insufficient financing. On the local level, officials should work to ensure equitable care, particularly in areas likely to become hot spots.

Reform global cooperation.

Gaining momentum in recent years is One Health [PDF], a public health approach that emphasizes the connections between humans, animals, and the natural environment. Advocates say that integrating sectors and research disciplines—such as agriculture and livestock, veterinary medicine, and environmental pollution—is necessary to prepare for future global health threats.

There’s been some headway made on boosting cooperation at the WHO in recent years, particularly since the emergence of COVID-19. In late 2021, the WHO and Germany launched the Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence, which is intended to improve data sharing and expand access to disease forecasting tools. More recently, WHO member countries agreed to draft a legally binding treaty to boost global coordination on pandemic prevention and preparedness, but deliberation on it will take years, and health experts disagree on what to include and whether it would be effective. Many experts working at the intersection of climate and disease emphasize that the cost of prevention would be a fraction of what countries have to spend on crisis response.

Reduce emissions.

To prevent the world’s average temperature from rising further, people have to stop releasing carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping greenhouse gasses, as well as remove existing emissions from the atmosphere. “We need to intervene at multiple levels, including the burning of fossil fuels, and treat that as an urgent health need,” says Jonathan Patz of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. However, countries have been slow to follow through on pledges they’ve made under the Paris Agreement on climate, including to reduce their emissions and reforest large swaths of land. Under current policies, the world’s average temperature is projected to rise by 2.5°C (4.5°F) compared to preindustrial levels by 2100, which is well beyond the 1.5°C (2.7°F) goal set by the Paris accord.

Will Merrow created the graphics for this article. Sabine Baumgartner curated the photos.

Recommended Resources

For Think Global Health, journalist Andrew Mambondiyani looks at how climate change is affecting the range of tsetse flies in Zimbabwe, and physician Vinayak Mishra argues for building resilience to climate-linked diseases in India and other vulnerable countries.

In this CFR report, Conservation International’s Neil Vora and Weill Cornell Medicine’s Jay Varma discuss how to prevent and prepare for pandemics with zoonotic origins.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lay out the effects of climate on health.

This Backgrounder explains what the WHO does.

This 2022 study in Nature found that over half of known infectious diseases can be aggravated by climate change.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change examines the consequences of 1.5°C of global warming in this 2018 report.

Online Store

Online Store